Layers of sand, silt, rock, and other substances were laid down in North Dakota over millions of years. Some layers were brought by water eroding the surfaces of the mountains to the west. Other layers were brought by wind. Each of these layers has a name which represents a time period. Each layer has its own story of where it came from, the conditions under which it was formed, and the plant and animal life trapped within its layers. Dino Dakota by Kris Kitko (MP3)

We can use a chart, called a stratigraphic (strat ih GRAF ick) column (See Image 1.) to view the order of North Dakota’s stratigraphy. Stratigraphy (stra TIG raf ee) comes from two words. “Stratum” comes from a Latin word that refers to something spread or laid down. “Graph” comes from a Latin word that the Romans took from a Greek word meaning writing. So, a stratigraphic column is a way of “writing” the geology of North DakotaRead the stratigraphic column from the bottom to the top.

1. Below the Pierre Formation. There are 13,000 feet of layers below Pierre that were deposited over the course of 470 million years. About 8,000 feet below Pierre are the Bakken and Three Forks formations where oil is located.

2. Pierre Formation and Niobrara Formation. Pierre and Niobrara are the lowest (or earliest) layers exposed in North Dakota. Some of the Pierre can be seen in extreme southwestern North Dakota. The Pierre and the Niobrara are also exposed in Cavalier county. This layer was deposited about 72 million years ago as sediment of the Western Interior Seaway. The fossils in the Pierre Formation include sea creatures such as Plioplatecarpus(mosasaur) and the Archelon (sea turtle.)

3. Hell Creek formation. Named for a creek in northeastern Montana, the Hell Creek formation is famous for its fossils. Hell Creek fossils include triceratops and other dinosaurs. It was deposited about 67 to 65 million years ago. The Hell Creek formation is exposed in southwestern and south central North Dakota.

4. Ludlow, Cannonball, and Slope Formations. These formations were deposited after the dinosaurs had become extinct from about 65 to about 62 million years ago. These are the layers where coal can be found. Dark coal seams are often exposed along the river banks and canyons of southwestern North Dakota.

5. Bullion Creek and Sentinel Butte. These two layers are the colorful formations that make Theodore Roosevelt National Park so beautiful. Bullion Creek formation is usually yellow and tan. Sentinel Butte is grey and brown. The fossils of ancient trees (petrified trees) can be found in these formations along with fossilized clams and snails.

6. Golden Valley, Chadron, Brule, and Arikaree. These formations represent the era of the three-toed horse (Mesohippus), crocodiles, and other animals that no longer live in North Dakota. This was an era of dry climate and small streams rather than swamps. Fossils of these animals are rare. Research is underway to find more evidence to tell us what North Dakota was like 55 to 24 million years ago.

7. Pliocene Epoch. The Pliocene marks a major change in the direction of the Missouri River. Until this time, about 2.6 million years ago, the Missouri River ran north. But the first great push of glacial ice sheets into North Dakota began to push the river southward. The river left several lakes (Williams, Turtle, and Brush Lakes in McLean County) behind as it worked out a new channel.

8. Pleistocene Epoch. During the Pleistocene, there were many changes to North Dakota. It was the time of the Ice Ages. Ice Age animals included mammoths, mastodons, giant bison, and ancient horses. Humans migrated into North Dakota. The Red River Valley formed and the central part of the state was left with millions of erratic rocks lying on top of soil. After the Ice Age, North Dakota became a great grassland.

The stratigraphic column shows the layers that underlie North Dakota’s surface. Some of these layers are exposed, others are deeply buried and we only know about them through core sampling. Each layer corresponds to a time period usually measured in millions of years. Each layer has its own story of climate and plant and animal life. If we look into a particular formation, we have a pretty good idea about what kind of animals or plants we will find there. If we study the Hell Creek Formation of the late Cretaceous (kree-TAY-shush) Period, we will find fossilized bones of dinosaurs that lived in that Formation. Hell Creek ended about 65 million years ago. The layers that were deposited after Hell Creek contain different kinds of rocks and different fossils.

The epochs, periods, and eras are dated in terms of millions of years. Though these dates change a little (by a few million years) as geologists accumulate more information, they are helpful in making sense of how long it took for geological changes to take place. The dates are determined through scientific study. Carbon dating can be used on materials that are less than a million years old. However, life forms that appear as fossils in rocks cannot be carbon dated because all of their carbon-based matter has been replaced by minerals. (See Image 2.)

Another method for dating strata is potassium-argon dating. Potassium and Argon are found in volcanic ash. A layer of volcanic ash from any eruption anywhere in the world can be dated. Geologists collect this information and use it to track ash layers. This method can be used to date rocks as old as 4.5 billion years old.

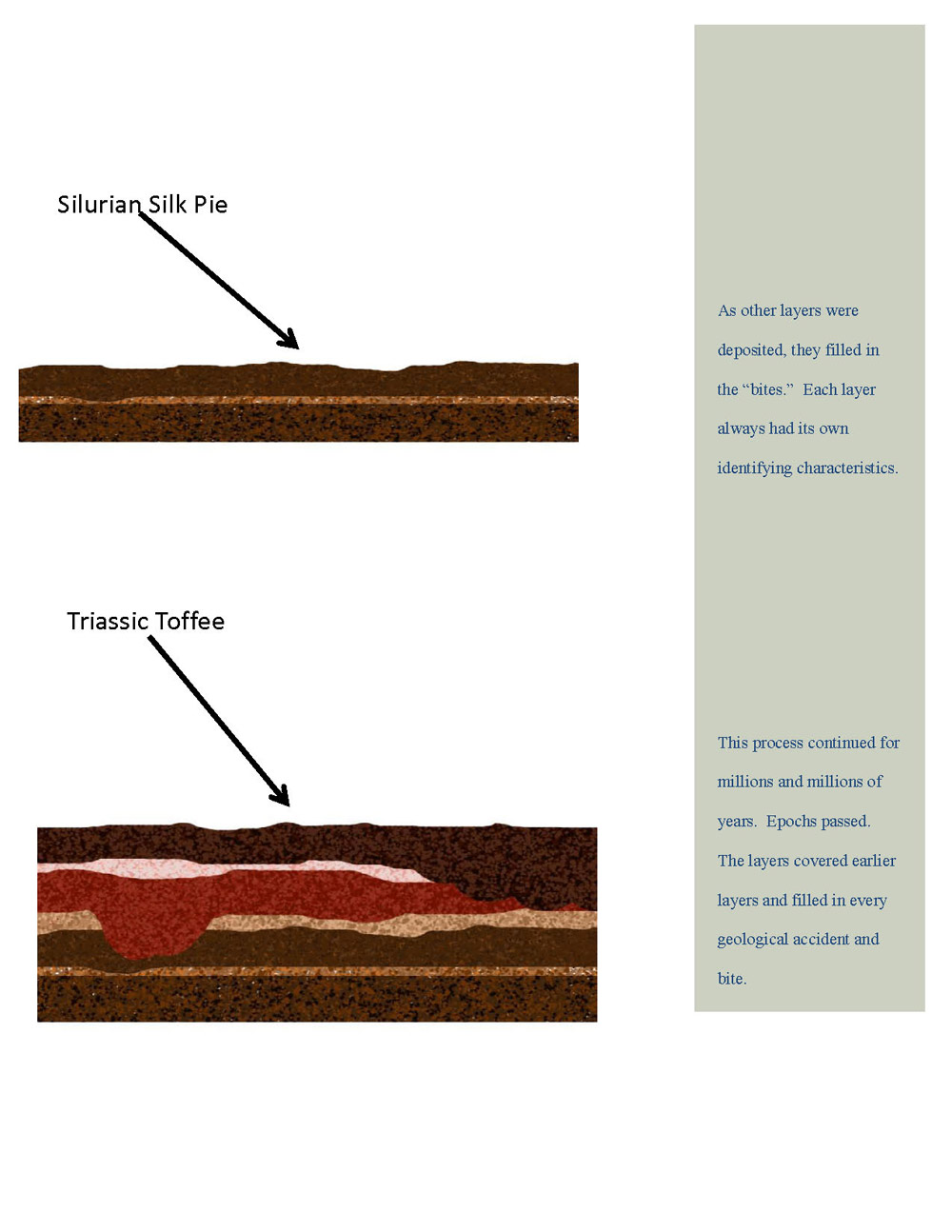

It might be helpful to think of the layers on which North Dakota sits as being like a layer cake. Layers were laid down over long periods of time, but little accidents or “bites” removed parts of those layers. The bite may have been a river flowing through a relatively level layer that formed under an inland sea. Sometimes a shift in the earth’s crust caused the surface to drop in one area. After the layers were in place, erosion by wind, water, or ice, cut away the layers, so that today, parts of all the layers are visible in some parts of North Dakota. (See Cake Images.)

A good place to see formations is in the badlands of western North Dakota. We are attracted to Theodore Roosevelt National Park because of the beautiful exposed layers of ancient rock formations that form the backdrop to the Little Missouri River. These rock layers were deposited during the Paleocene (PAY lee o seen) Epoch between 60 and 50 million years BPE. The two main layers are the Bullion Creek and the Sentinel Butte formations of the Paleocene Epoch. Bullion Creek, the older (and lower) formation, is bright yellow and tan. Sentinel Butte is grayer and browner. Other layers add to the colors, including HT Butte clinker which is the hardened red rock left from burned coal. Bentonite clay is the light bluish-gray that adds another layer of color to the cliffs in the badlands. Sentinel Butte and Bullion Creek formations contain fossilized animals (not dinosaurs). There are also plant fossils including the petrified trees that you can see if you hike through the park.

Why is this important? Though North Dakota (and everywhere else, too) was put together in cake-like layers, the effects of wind, water, ice, and tectonic shifts along the earth’s crust have opened those layers to give us geological information of our very distant past.

The organization of the layers and the fossils they contain teach us how the earth formed and how plants and animals lived, died, and evolved. The geological evidence captured by formation tells us that geological formations, plants, and animals are part of a dynamic, ever-changing earth.