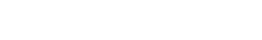

The Lakotas and Yanktonais (Sioux) attended the Great Council at Fort Laramie in 1851. The treaty assigned a large territory to the Lakotas and Yanktonais (See Map 5). They were expected to live in the area west of the Missouri River, south of the Heart River and north of the territory of Nebraska. However, the tribes were given access to more land to the west and north where they could hunt.

The treaty was soon broken by the building of Army posts and trails through the treaty lands. The Lakotas resisted these violations of the treaty. Some went to war against the Army and discouraged settlement and travel by non-Indians.

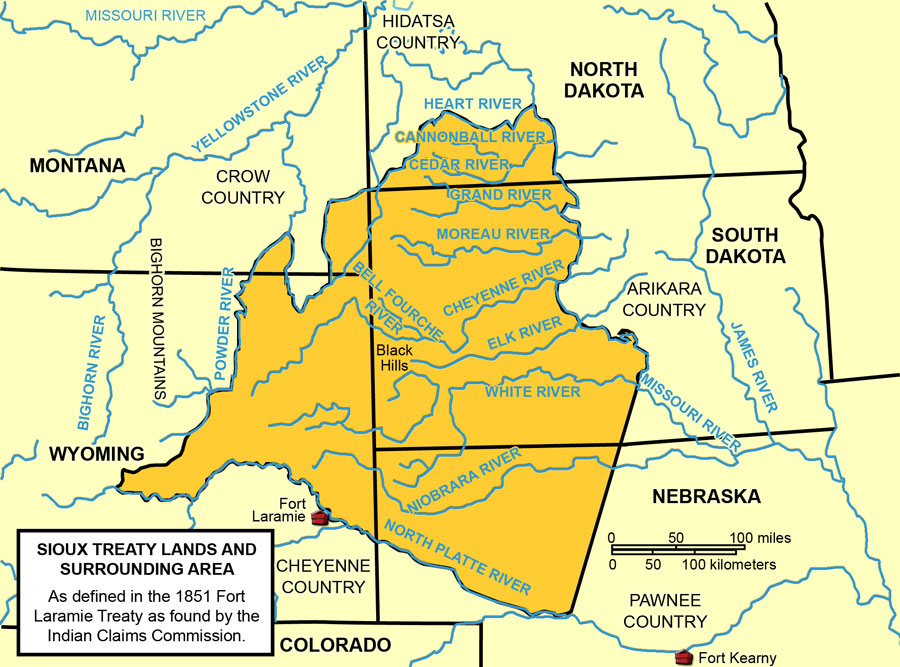

The United States Commissioner of Indian Affairs wanted peace in the northern Great Plains in order for settlers to develop farms and railroads to build through the region. Another peace council was held at Fort Laramie in 1868. This time, the treaty declared that much of the land identified by the Treaty of 1851 would be the homeland of the Sioux. It was to be called the Great Sioux Reservation (See Map 6) An agency was established at Grand River (in present-day South Dakota.)

Again, there were violations of the treaty. To the Lakotas, the most disturbing of these violations was the 1874 expedition to the Black Hills led by Colonel George Armstrong Custer. The men of this expedition brought back news to Bismarck that there was gold in the Black Hills. The government asked the Lakotas to cede (give up) the Black Hills which was part of Great Sioux Reservation. The Lakotas refused to cede this land which was the location of their most sacred sites.

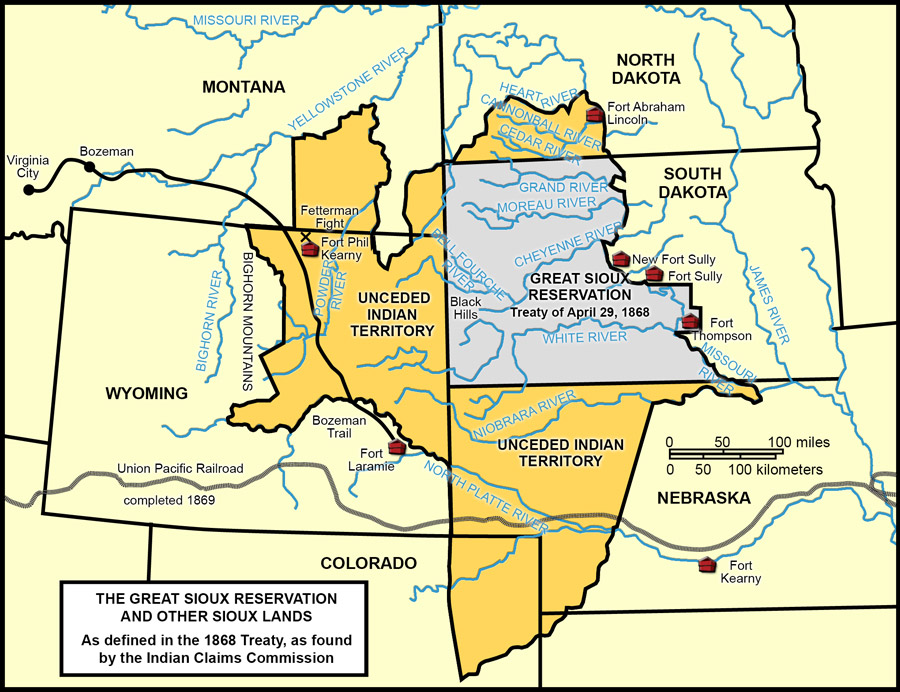

In 1876, the Lakotas, along with Cheyennes and others, fought with the Army at the Little Big Horn River in Montana. At this battle, the men of the 7th Cavalry, led by Colonel Custer, were all killed. The battle was a major defeat for the U.S. Army. As a result, the Black Hills were taken from the Great Sioux Reservation and officially opened to non-Indian settlement and mining. (See Map 7)

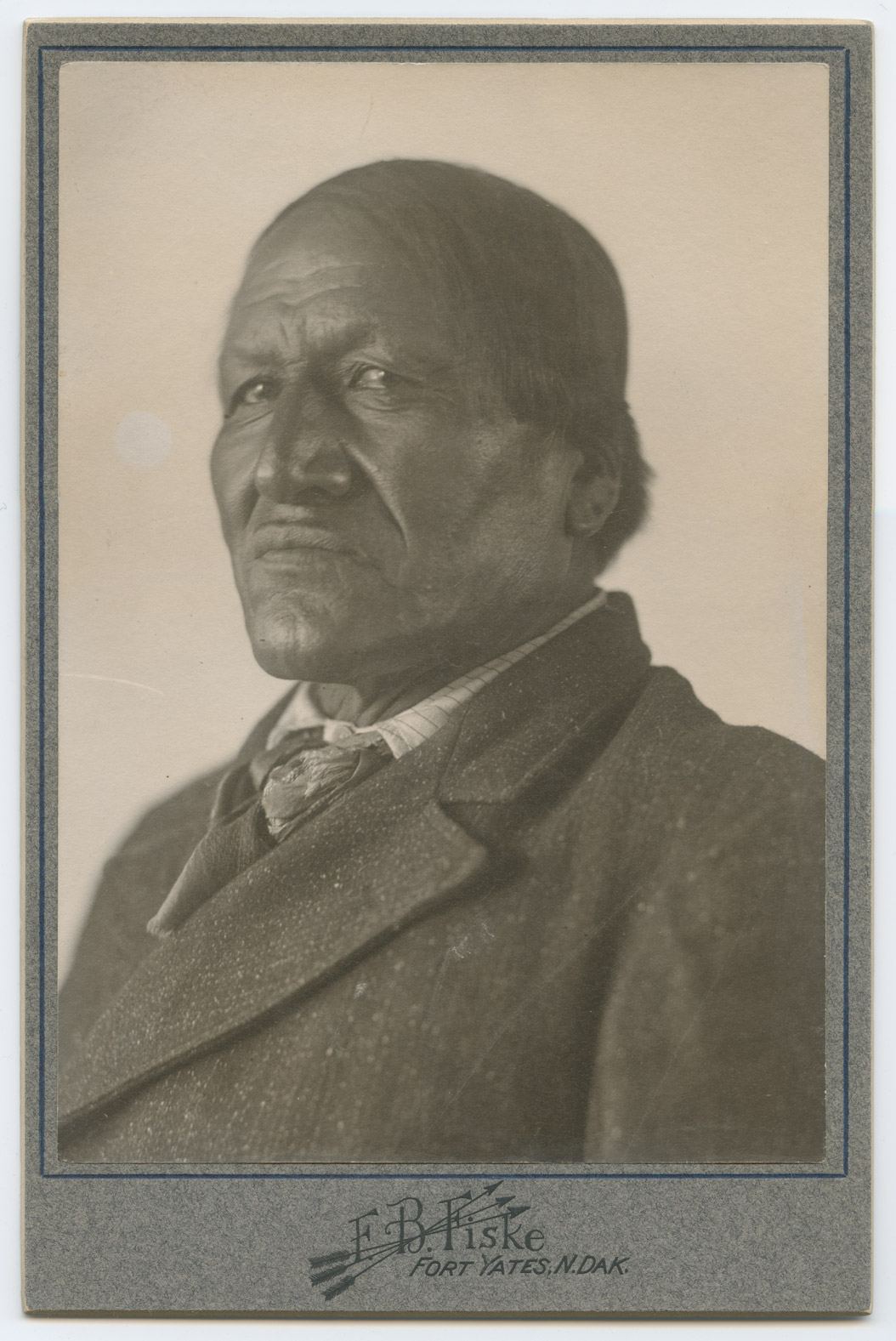

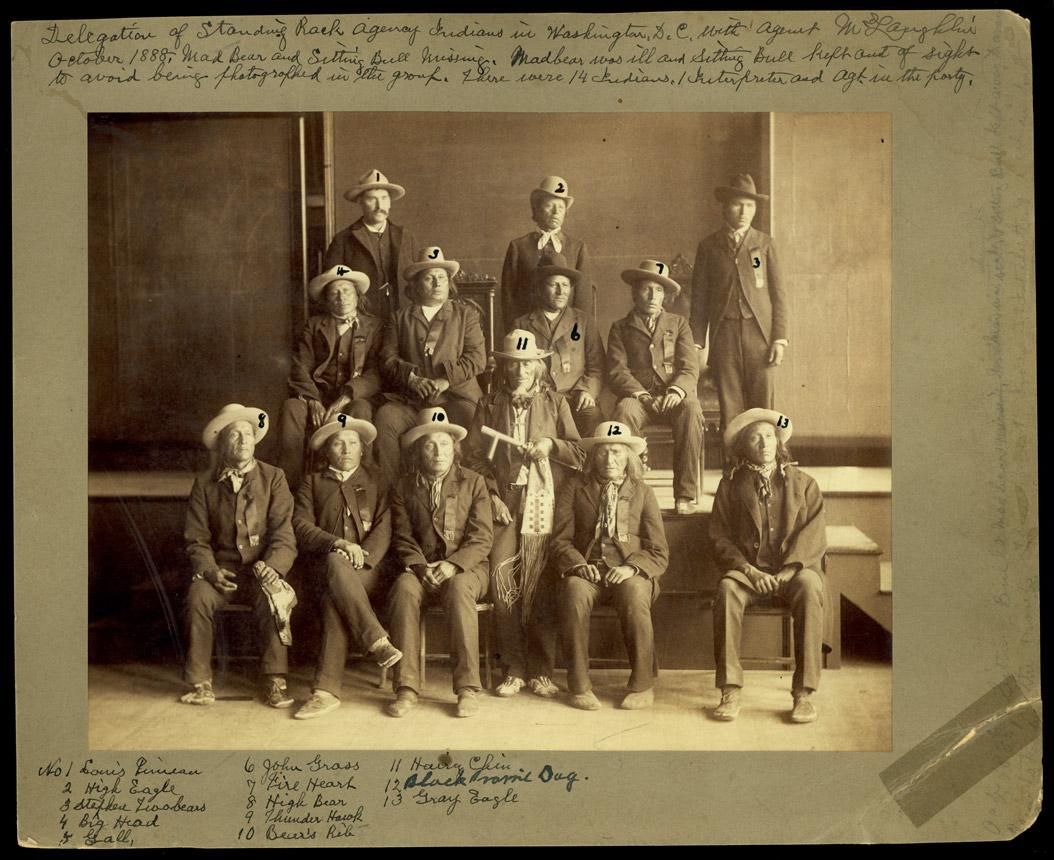

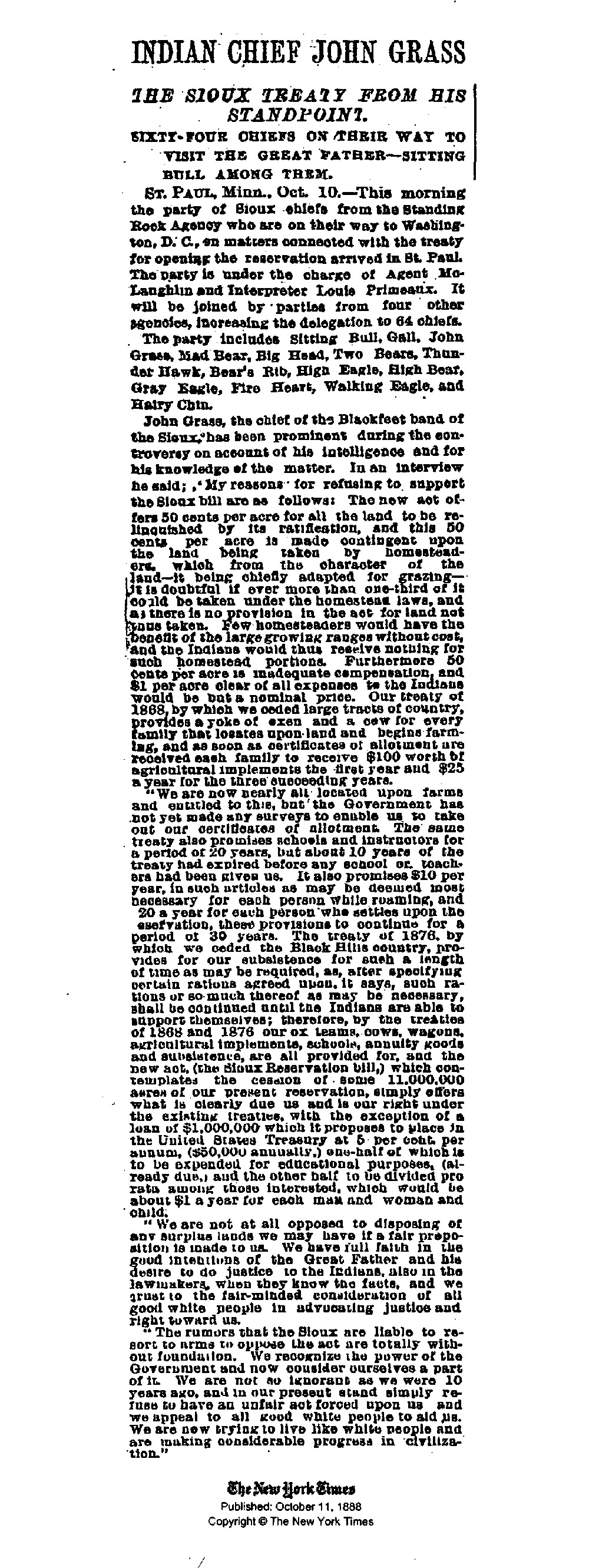

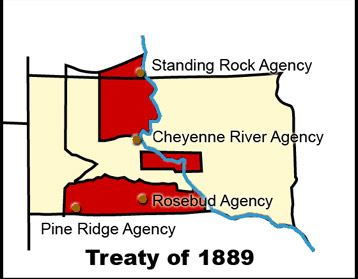

Another reduction in the reservation came about in 1889. The great Lakota leader, John Grass, protested the break-up of the Great Sioux Reservation (See Document 15). (See Image 8) A delegation went to Washington to impress on Congress the wishes of the tribes (See Image 9). Congress, however, proceeded and the reservation was broken up into smaller parcels (See Map 8). One of these smaller reservations was the Standing Rock Reservation which is located in both North Dakota and South Dakota. Most of the residents were Lakotas and Yanktonais.

Soon after Standing Rock Reservation was created, it was approved for allotment. The enrolled members received land according to their age and family status. As they tried to adapt to this way of life they had not chosen, they learned to farm, to bring crops to market, to raise cattle, and to live in log cabins on their own allotment.

In 1908, the federal government again approached the Lakotas and Yanktonais, Again, there were few choices, Congress wanted to take unallotted land and make it available to non-Indians. In 1910, portions of the reservation were opened to white settlement (See Map 9).

This section will help you understand the processes that caused the Standing Rock Reservation to have the shape it does today. As the reservation boundaries changed, the relationship between the tribes and the government changed. By 1915, many of the residents of Standing Rock had become U.S. citizens. It was a long process, often violent, very sad, and stressful for the Sioux. It is a difficult chapter in American and North Dakota history.