On July 1, 1862, President Lincoln signed a bill called the Pacific Railway Act that Congress had passed after 11 southern states had seceded from the Union. The bill offered federal support in the form of land and loans for the building of a transcontinental railroad.

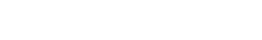

The Pacific Railway Act encouraged private corporations to build a railroad from Chicago or Omaha to California. Railway technology was ready for such a grand task. Inventions in rails, engines, fuel, and schedules made it possible for trains to carry heavy loads long distances. The Union Pacific Railroad was the first to cross the continent and completed tracks in 1869. (See Map 3.)

On July 2, 1864, President Lincoln signed a charter to create a second transcontinental railroad. This one, the Northern Pacific Railway (NPRR), was to cross the country between Lake Superior (eastern Minnesota) and Puget Sound (near Seattle, Washington.) The NPRR had to cross the badlands of northern Dakota Territory, build bridges across several rivers, and climb the Rocky Mountains before it reached the ocean. The Northern Pacific opened up the great wheat country of Dakota Territory to transport of crops, people, and manufactured goods. In addition, the rails hauled timber from Montana and Idaho to eastern cities. The NPRR would also connect manufacturers in eastern states to ships sailing the Pacific Ocean toward Asian markets.

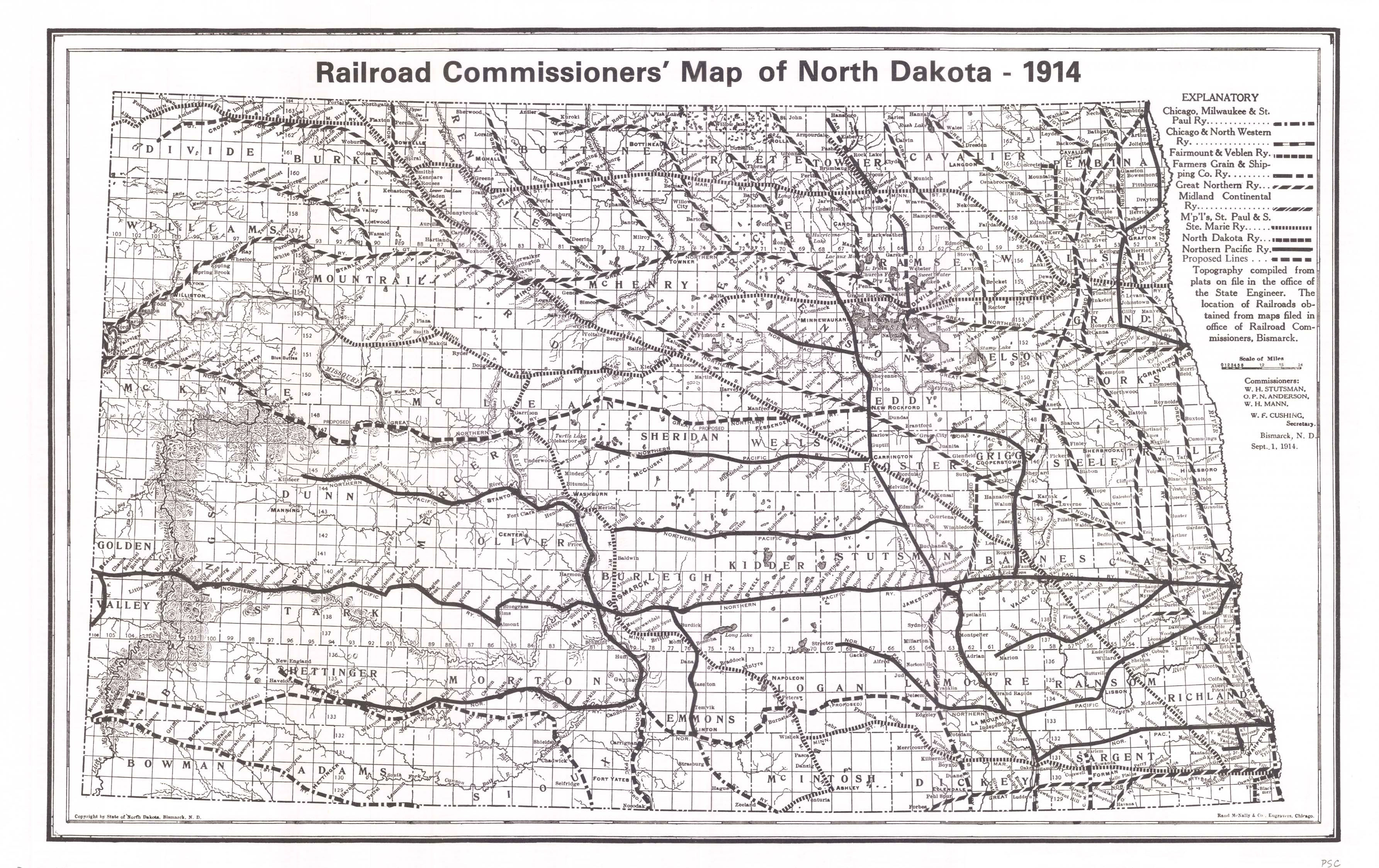

The Northern Pacific began construction in 1870. It set up rail centers in Fargo, Bismarck, and Dickinson. (See Image 15.) Along its route, the NPRR platted (mapped) towns where trains could get water and fuel, load and unload freight, and pick up passengers. Railroad towns were built about every seven miles along the main line of tracks. Settlers could sell grain, eggs, milk, and cattle in railroad towns. Farm families could buy groceries, clothes, lumber, and farm equipment in the towns because the railroad transported goods from distant mills and markets.

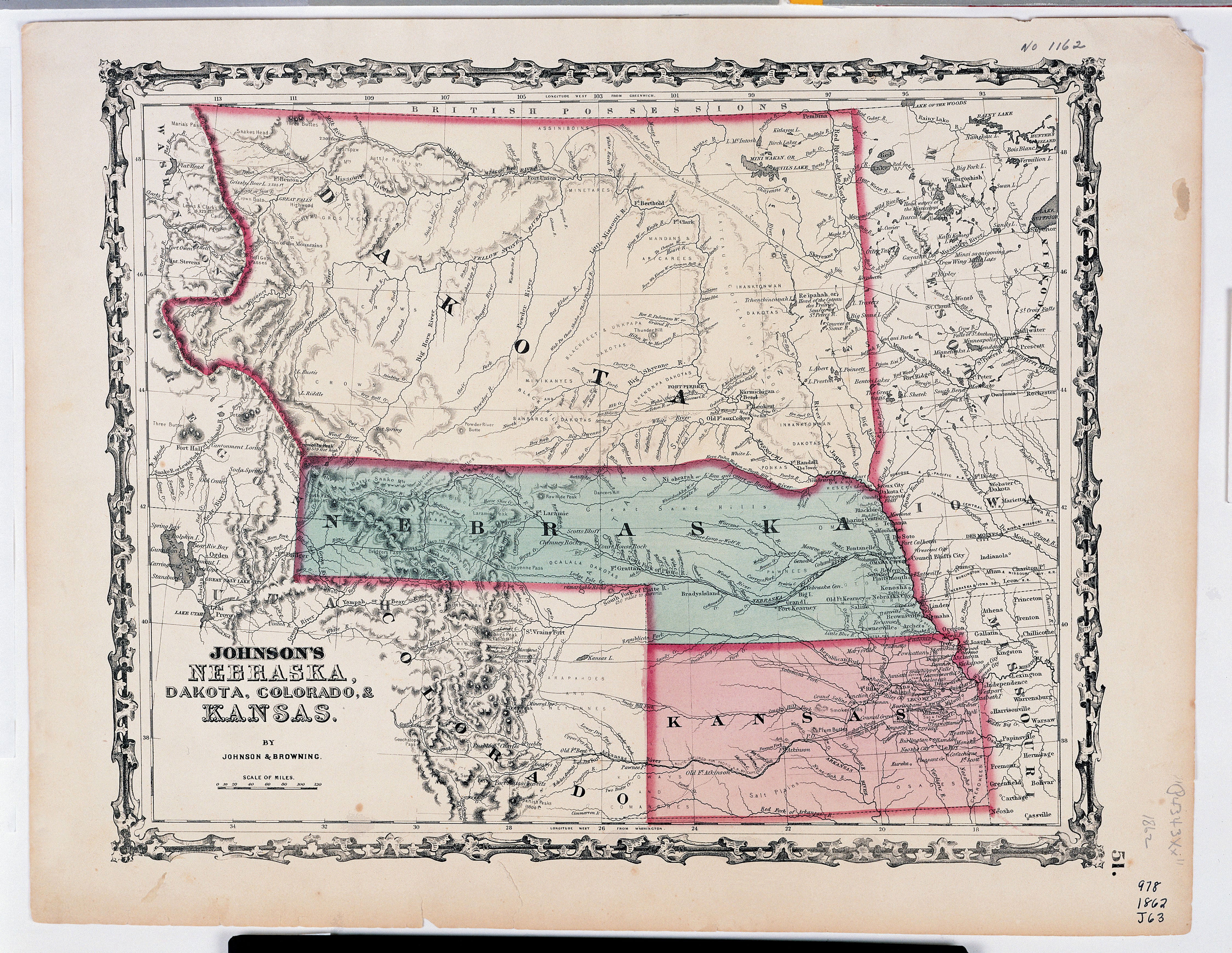

In June, 1873, the Northern Pacific reached the tiny village of Bismarck. (See Map 4.) Then, the NPRR declared bankruptcy and construction ended until 1879. Finally, in 1883, the railroad completed its tracks with a Golden Spike ceremony in Montana. The president of the railroad, Henry Villard, invited a trainload of guests, including former President Ulysses S. Grant, to join him in the ceremony. (See Image 16.) When Villard’s four special trains passed through Bismarck, (See Image 17.) he visited the site of the new territorial capital. (See Image 18.)

Why is this important? Perhaps no other event was more important to the growth of Dakota Territory than the building of the Northern Pacific Railroad. Settlers loaded their families and their farm equipment onto rail cars to move to Dakota. Farmers shipped wheat to St. Paul and Duluth to be milled into flour. Theodore Roosevelt and other easterners came to Dakota on the train and found a good place to raise cattle. Trains carried their cattle to market. Transportation was the key to growth. (See Map 5.)

There were some changes associated with the railroad that were not good. The NPRR was one of several events that forced Indian tribes, especially the Lakotas, the Mandans, the Hidatsas, and the Arikaras, to give up their treaty lands and move to reservations. The trains contributed to the near-extinction of bison. The railroad also controlled the political events of North Dakota for many years.

Today, the Northern Pacific Railroad is the Burlington Northern. Though many miles of spur lines connecting the main line to small towns were built by 1920, today miles of track have been removed.

Many events in history have both good and bad aspects (or sides). The railroad can be valued for the good; it can be criticized for the bad. However we look at it, the Northern Pacific Railroad brought permanent change to the land and the people.

Pacific Railway Act: The Land Grant

The Northern Pacific Railroad received land from the public domain which was land owned by the federal government. Congress granted the NPRR 40 sectionsA section is 640 acres. Each section was measured by a surveyor and given a series of numbers which identified its location. This system of dividing up the public domain was created by Thomas Jefferson in the 1785 Land Ordinance. The system was retained in the 1787 Northwest Ordinance. per mile in Dakota Territory. That amounts to 25,600 acres for every mile of track completed. Every other section was still available to homesteaders. The system created a checkerboard pattern. (Image 19.) In the illustration, the green sections belonged to the NPRR; the white sections were in the public domain. Each section is a mile long on each side, so there were 20 green sections on the north side of the tracks and 20 green sections on the south side of the tracks for every mile of track.

Ranchers who used the public domain for grazing often used railroad land, too. Some ranchers, including A. C. Huidekoper, purchased railroad land. However, Huidekoper could not buy or rent land in the public domain, so he used it without paying rent. He built a fence around the entire range, which enclosed the land he owned and the public land he did not own. When potential homesteaders complained that Huidekoper had fenced the public domain, he had to pay a fine and give up his use of public land.

Why is this important? The Northern Pacific Railroad land grant forced changes in the reservations. The residents of Fort Berthold Reservation gave up many acres of land in order for the Northern Pacific Railroad to receive its land grant in the usual pattern. Homesteaders often found railroad land more appealing, but it also interfered with their ability to acquire contiguous (next to each other) parcels of land. The land grants supported the building of the railroads, but privately built railroads such as the Great Northern were also successful in North Dakota.

Building and Financing the Northern Pacific Railway

The building and financing (finding the money) of the Northern Pacific Railroad (NPRR) was quite complicated. Congress gave the railroad 12,800 acres of land per mile of track in the states, and 25,600 acres per mile of track in the territories. This land could be sold, or the company could build towns and railroad centers on the land.

The NPRR used the land to secure financing. This means that investors, the people who had money to lend to the company for construction, were told that their money was safe because of the value of the land that the railroad received for every mile of track laid.

On January 1, 1870, the company asked an important banker, Jay Cooke, to sell bonds for the railroad. Cooke had a good reputation as an honest businessman. Many people purchased the bonds because they believed him when he said it was a good investment. Cooke worked hard to sell the bonds. He promised the NPRR officers that he would have $5,000,000 for them within thirty days so they could begin construction.

No one knew how much it would cost to build this railroad. It had to construct 2,000 miles of track. There were few towns along its route. Indian tribes had not yet ceded (given up) much of the land where the train would run. Some people estimated that it might cost $85,000,000 to build the railroad. This railroad was the largest business venture anyone had ever started in the United States.

Financial problems soon appeared. The officers of the company did not invest their own money in the railroad. Their system of accounting for money earned and money spent was so disorganized that no one could find out how much was spent to build the tracks. The company did not manage construction properly and spent too much money.

Jay Cooke had to find more money whenever the railroad executives made mistakes. Eventually, his bank lost all its money trying to keep up with the NPRR’s expenses and had to declare bankruptcy. When Jay Cooke lost his money, the whole country worried about business failures. The railroad surveyor, Thomas L. Rosser, was heading home from Bismarck when he heard the bad news. He wrote: “[I] learned that Jay Cooke & Co. had failed and the future of our company is dark and uncertain. . . .”

The failure of the NPRR and Jay Cooke and Company started the Panic of 1873. A panic meant that many businesses failed, some people lost their jobs, and few new businesses were started.

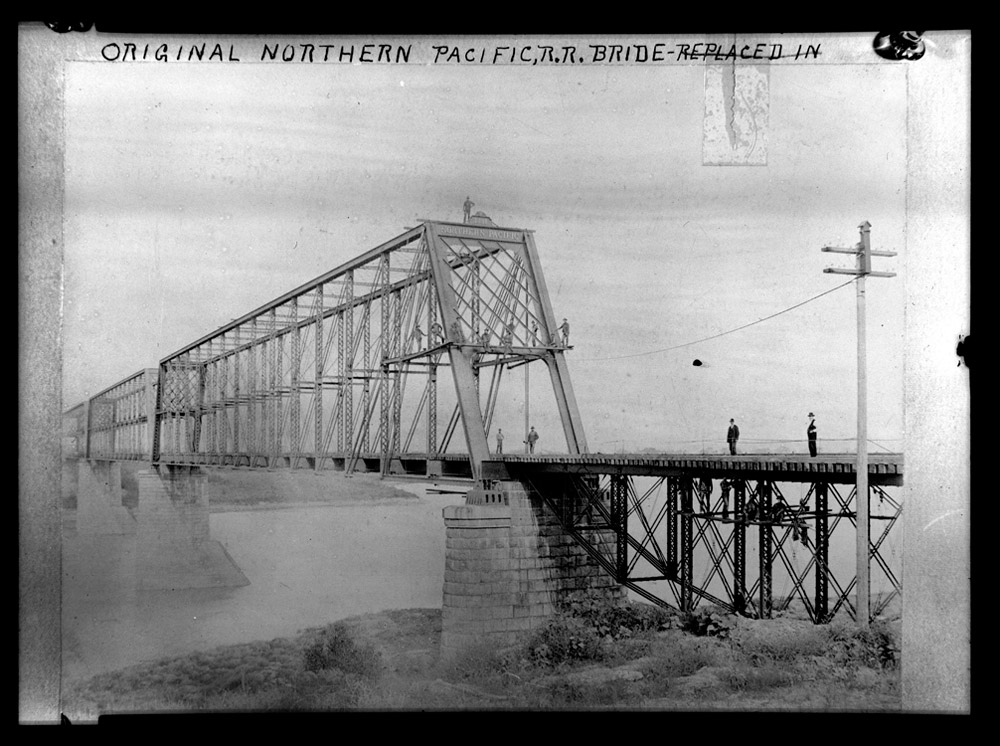

By 1873, the NPRR had built tracks to Bismarck. The engineers had built bridges across the Red River, the Sheyenne River, and the James River. (See Image 20.) The land had to be leveled to accommodate the tracks. (See Image 21.) Engineers were unable to build a bridge across the Missouri River for several years. In the meantime, ferries carried freight across the river. (See Image 22.) One very cold winter, rails were stretched across the Missouri. Trains crossed the river on an ice “bridge” until the weather warmed up. (See Image 23.)

The Northern Pacific recovered financially and began to build tracks again in 1879. The westbound tracks met the eastbound tracks in Montana to complete the line in 1883. (See Image 24.) Freight and passengers were able to travel from Minnesota to the Pacific Ocean. Residents of northern Dakota Territory could receive mail regularly and travel east or west to conduct business or visit their families.

Why is this important? The Northern Pacific Railroad was a big company that affected the economy of the entire U. S. It was building into a place where there were few people and little business. However, the railroad and its investors believed that trains would bring people and freight to the region. It was a huge and risky step that symbolized the movement of the people, economy, and cultures of the United States onto the northern Great Plains. Without the Northern Pacific, the northern portion of Dakota Territory would have developed at a far slower pace.

The Northern Pacific Railroad and the Bonanza Farms

The Northern Pacific needed to sell land to immigrants to raise construction and operating funds. It set up an office in London to attract Europeans to Dakota Territory and other places along the tracks. At first, no one bought land in Dakota Territory. Even the NPRR’s land agent, James B. Power, thought Dakota was a “barren desert.”

-Northern-Pacific-Railroad-Line-circa-1875-Broadside-chromolithograph-optimized.jpg)

Then, James Power had a new idea. When the NPRR went bankrupt, it began to sell its stock and land for 14 per cent of its value. Land valued at $2.50 per acre sold for 35 cents per acre. Power thought that land at that price might encourage speculators (people who buy land so they can re-sell it for a profit, not to live on or farm.) Speculators would discourage farmers from buying the land. The railroad needed farmers who would raise crops and ship grain by railroad to eastern markets.

Power convinced the president of the company, George Cass, to start a farm on railroad land to demonstrate how farmers could make a good living in Dakota. Cass agreed, and with his friend George Cheney, bought 13,440 acres of land about 15 miles west of Fargo. They hired Oliver Dalrymple to manage the farm. (See Image 25.)

The railroad was re-organizing, but it was not yet building new tracks west of Bismarck where it had stopped in 1873. It was a good time for the company to demonstrate the importance of its land grant. Between 1873 and 1878, Power sold 1,700,000 acres for a total income of $7,900,000. Land sales pushed the value of railroad land to $4.50 per acre. By 1881, most of the land grant between Fargo and Jamestown had been sold.

The success of the large farms on NPRR land brought more people to Dakota Territory. Investors purchased large tracts of land for bonanza farms (at least 3,000 acres in size) in the Red River Valley. In all, there were 91 bonanza farms in the last 25 years of the 19th century. Congressmen, manufacturers, newspaper editors, and even two members of the British Parliament came to see the bonanza farms. Dakota became a familiar word to all Americans. (See Image 26.) No. 1 Hard wheat was the key to wealth in northern Dakota Territory.

Why is this important? In 1873 and 1874, after the Northern Pacific tracks reached Bismarck, there was a national debate about whether northern Dakota Territory soil could support farmers and their families. James Power’s idea to start demonstration farms resulted in highly successful bonanza farms. The success of these huge farms convinced people that the land that had once been called the Great American Desert was not to be feared or avoided, but could support farms, families, and towns.

The Northern Pacific Railroad and the Teton Dakotas

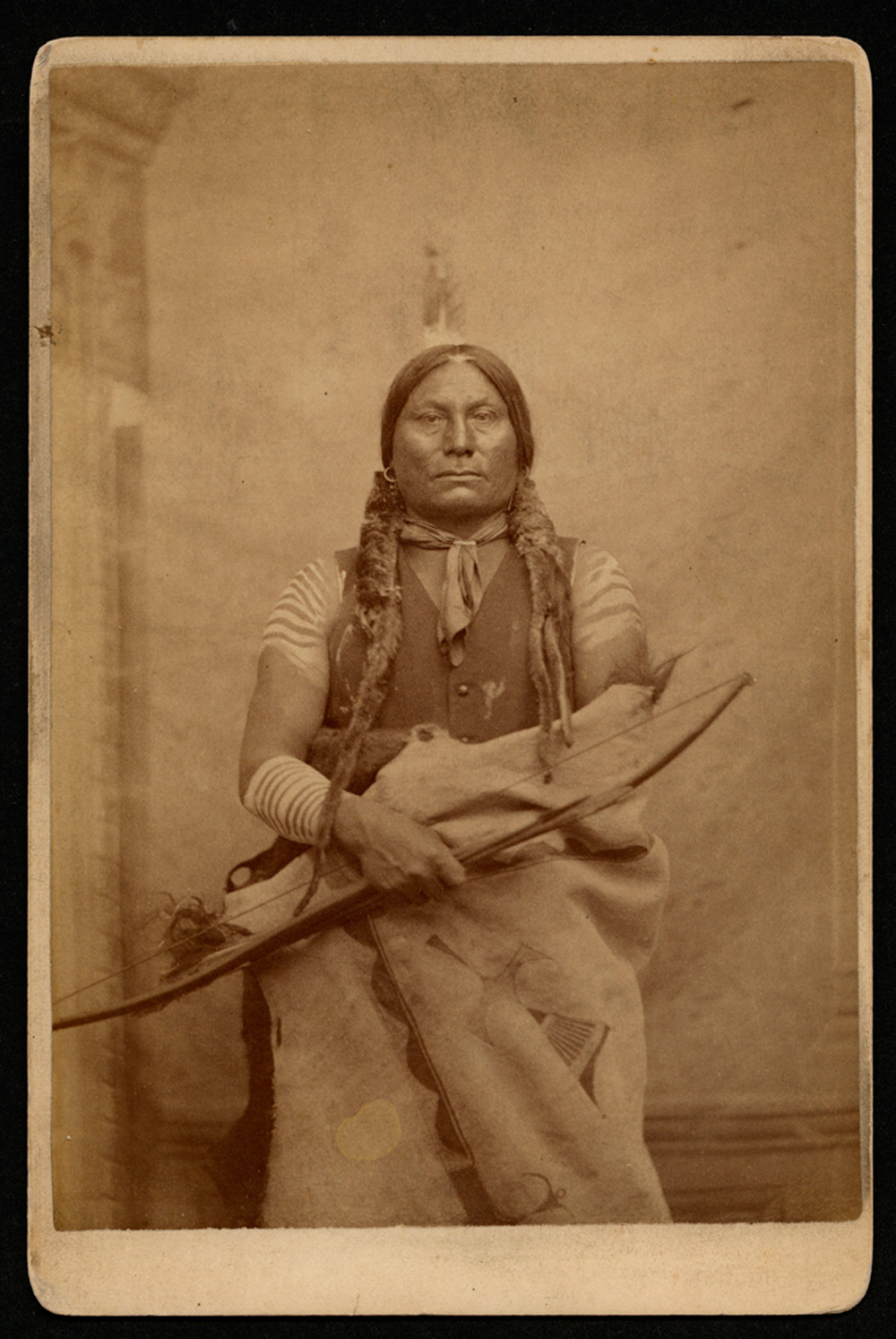

The Teton Dakotas were the largest tribe of American Indians on the Great Plains in the mid-19th century. The Hunkpapa and Miniconjou bands of the Dakotas, tried to keep the Northern Pacific Railroad (NPRR) out of their homelands. Sitting Bull and Gall (See Image 27.) were the leaders of the effort.

When the NPRR began building into Dakota Territory, the Tetons understood that the railroad would bring big changes to their tribe. The president of the NPRR knew that Dakotas would resist, or fight, construction of the railroad through their treaty lands. The railroad company had been warned in 1872 by Spotted Eagle, a Sans Arc (Itazipco) Teton, that the Dakotas would not allow the railroad to build through their homelands. The Teton Dakotas were so determined to protect their treaty lands that railroad crews required military protection while they surveyed the route across Dakota Territory and Montana.

The NPRR’s chief engineer, Thomas Rosser, made several surveys to determine the best route of the tracks west of the Missouri River. The first survey was in the fall of 1871. There was a second survey in the summer of 1872 and another in 1873. The Dakotas did not bother the first survey party. In August 1872, Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse led a war party against the surveyors in southern Montana. A few days later, Gall led an attack on the soldiers protecting the survey crew. Gall demanded that the Army and the surveyors leave the Dakota’s country or they would face more violent resistance. Sitting Bull arrived with his men to back up Gall’s demands. The Hunkpapas and the soldiers engaged in a battle with no definite outcome.

As the troops returned to Fort Rice, a few soldiers rode ahead of the main group. Gall was following them, but staying out of sight. When Lt. Eban Crosby left the column to hunt pronghorn, Gall saw him and attacked. Crosby was killed.

The next day, another officer, Lt. Louis Adair and an African American cook, Stephen Harris, also left the main group of soldiers to hunt. Gall caught and killed these two men and taunted the soldiers by showing them the scalps of the men he had killed. Lt. Adair was a cousin of Julia Dent Grant, the wife of President Ulysses Grant. Because the president’s family was involved, Gall became famous among non-Indians. Many non-Indians were angry because they believed that Gall’s attack on the soldiers was not justified.

In 1873, General Sheridan, who was in charge of the Army in the Northwest, sent 1,500 soldiers to protect the surveyors. This time, the railroad was looking for a good route to the Yellowstone River. Colonel George Armstrong Custer led part of the expedition. On August 4, a small group of Hunkpapa warriors attacked Custer’s 7th Cavalry. The soldiers successfully defended themselves.

On August 11, the Hunkpapas returned with Miniconjou and Cheyenne warriors. Gall led the attack on Custer’s command. The 7th Cavalry was well-prepared for battle. The soldiers had a fortified position on high ground. Once again, the soldiers stood their ground until the Tetons and the Cheyennes left. However, the soldiers learned that the Tetons had good rifles and were stronger in battle than they had been before. One soldier died in the battle and three were wounded. Historians don’t know how many Tetons and Cheyennes might have been killed.

The Dakotas could not stop railroad construction, but their resistance to railroad construction caused several political problems. Those who believed that Indian lands were being taken illegally asked that Indian tribes be treated fairly. It is possible that the conflict over the railroad caused some railroad investors to wait until the “Indian Problem”The “Indian Problem” was a term commonly used in the 19th century. It was a sort of code term to cover a range of issues. The Indian Problem referred to conflict between the U.S. government and American Indian tribes over control of the land; assigning Indian tribes to reservations; and educating the children of American Indians. To some people, the solution to the “Indian Problem” was to establish reservations. Others thought that issues of cultural and territorial conflict could only be resolved by military action. Still others, often grouped under the label “Friends of the Indian,” believed that Indians could be educated and change their way of life from their traditional culture to a culture similar to that of Anglo-Americans (also called assimilation.) was solved before investing in the NPRR.

In Dakota Territory, it was clear that building the railroad would result in violent conflict between the Dakotas and the Army. In 1876, three years after the Battle of the Yellowstone, the Army again met Sitting Bull and Gall in battle. This time, the battle was fought in Montana at the Little Big Horn River.

Why is this important? The Dakotas knew that the terms of the Treaties of Fort Laramie of 1851 and 1868 prohibited the railroad building across their treaty lands. The railroad not only laid tracks across their lands, but soon trains would bring people to build homes, farms, ranches, and towns. The new settlers wanted a peaceful place to live. The Dakotas knew that farms and towns would destroy their way of life. They did what they could to defend against this threat.

Railroad and Population

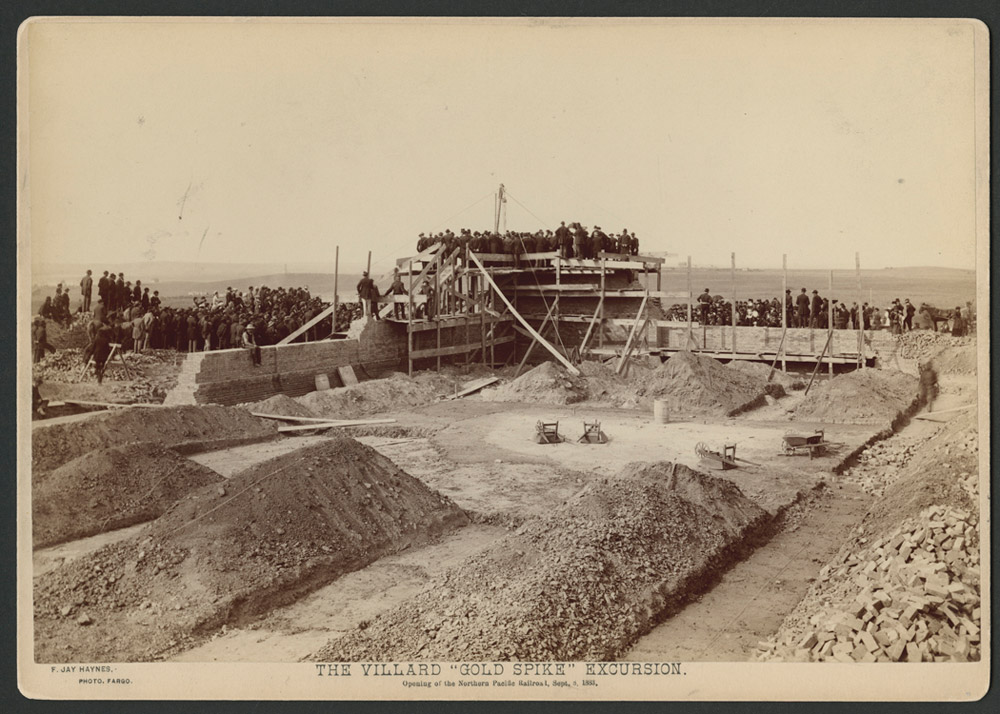

The Northern Pacific Railroad was so successful in stimulating economic growth in North Dakota that many other railroads followed its path to success. (See Map 5.)

The Great Northern Railroad and the Soo Line as well as many other smaller lines built tracks into North Dakota by 1914. The rails helped to increase the population of North Dakota. Railroad access to small towns allowed people to emigrate by rail. It was a much faster and more comfortable trip by rail than by wagon.

During those years, people traveled from town to town by train. People in very remote areas could take their crops to a nearby town and ship them to distant cities. Cattle or fresh butter could be put on a train in North Dakota on a Tuesday morning and be in Chicago (a major market center) by Wednesday morning.

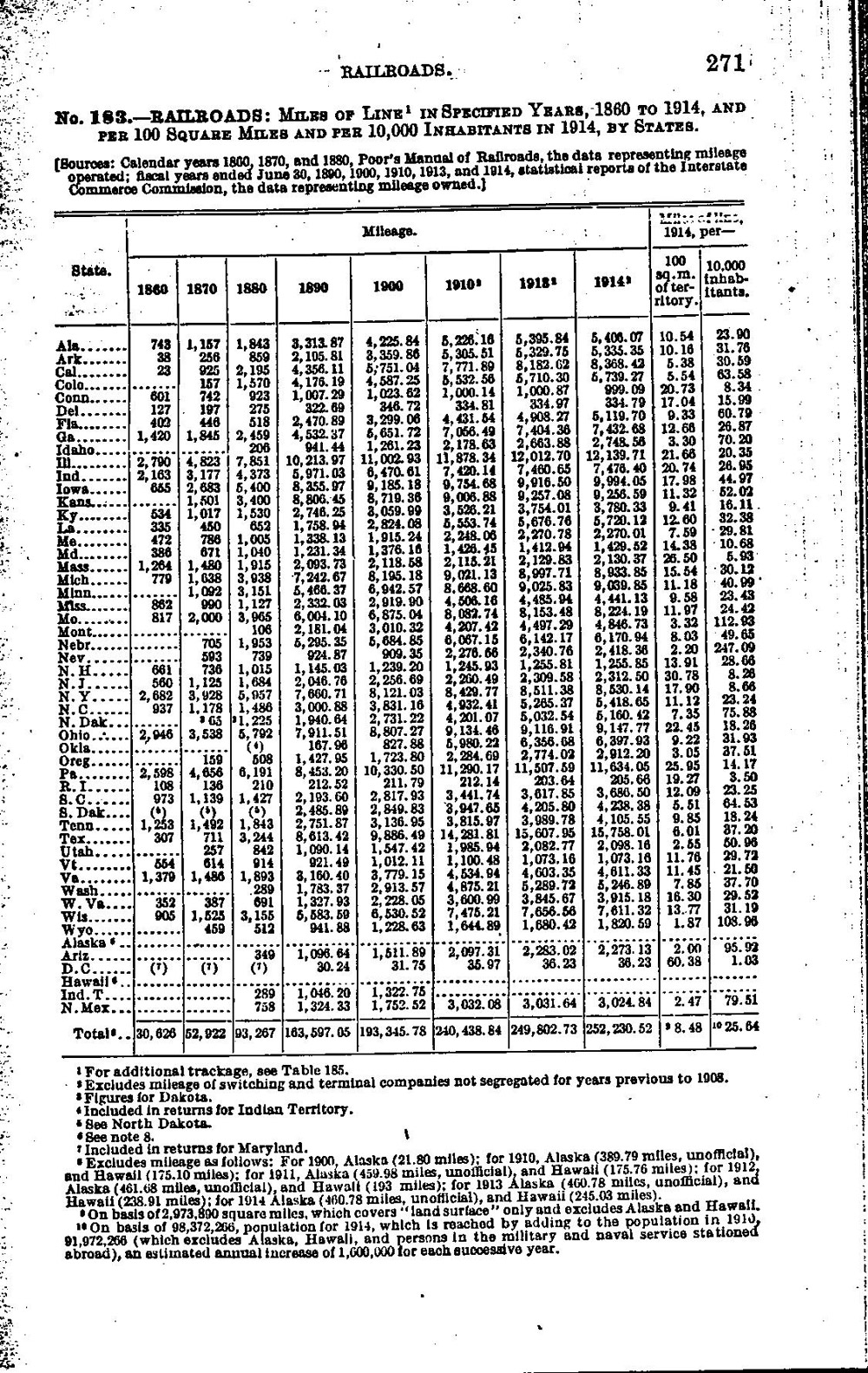

By 1914, North Dakota had more than 5,000 miles of track. Even South Dakota and Wyoming which are about the same size as North Dakota did not have as many miles of track.

The United States census gathered data on railroad track mileage in 1915. (See Document 6.) The data shows the rapid economic growth of western states and territories and how important they had become to the nation. North Dakota’s place in the national economy was secured by the railroads. North Dakota ranked fourth in the nation for number of miles per 10,000 residents.