The Washburn Coal Mine

In 1892, Ole Anderson and Albin Hedstrom opened a coal mine in northern Burleigh County. The first year of operation, Anderson and Hedstrom hauled 3,000 tons of coal by horse drawn wagon 25 miles to Bismarck. The coal was usually used for heating fuel.

In 1898, General William D. Washburn, a Minnesota politician and businessman, purchased 114,000 acres of land in Burleigh and McLean counties from the Northern Pacific Railroad for $1 per acre. Part of Washburn’s investment was for speculation. He planned to sell the land for development. He also knew that there was coal under the land because Anderson and Hedstrom had found coal in the area. In order to extract the coal and sell it, he needed a railroad from the coal region to Bismarck. In 1899, he organized the Bismarck, Washburn, and Fort Buford Railroad. The name changed to Bismarck, Washburn, and Great Falls Railroad in 1900.

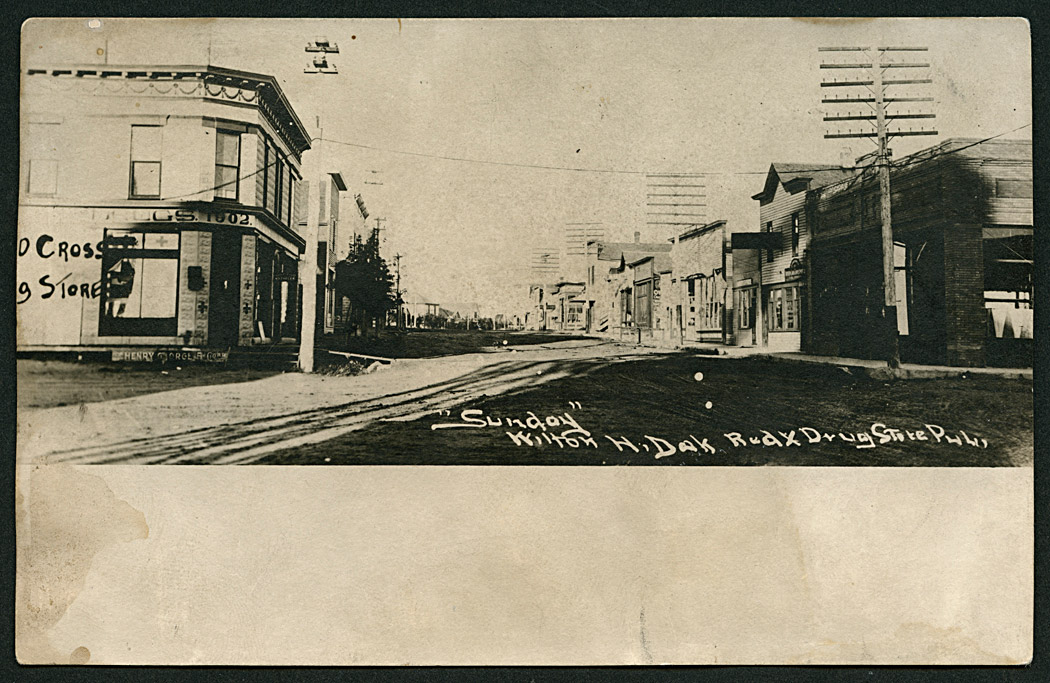

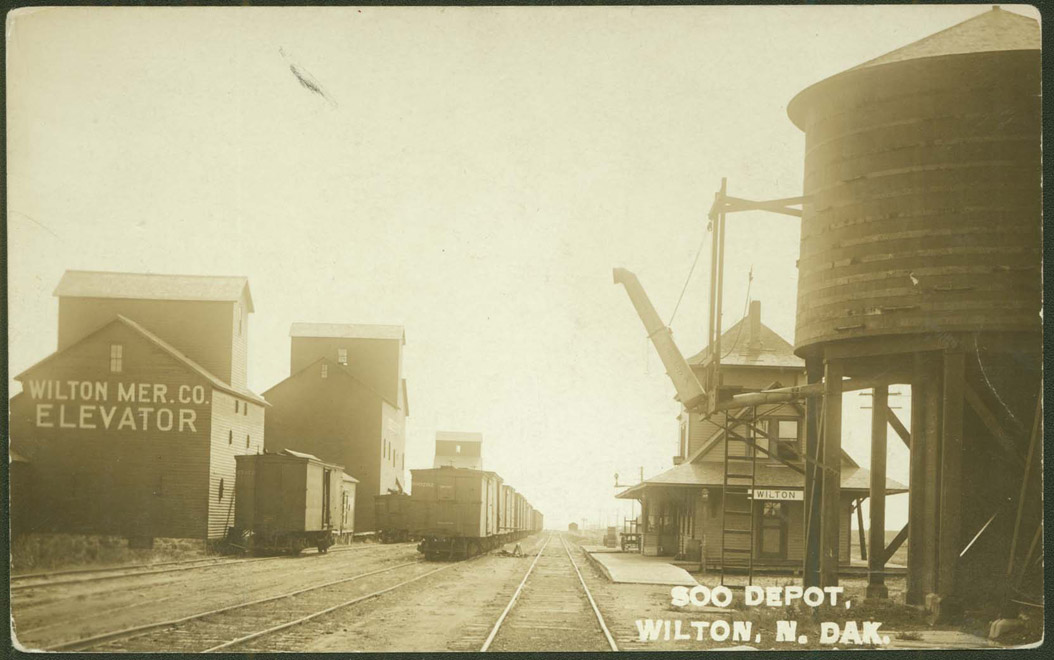

General Washburn hired Walter Macomber, (See Image 10.) a smart and efficient mine manager, to operate the Washburn Lignite Coal Company (WLCC). Macomber platted a town called Wilton and invited merchants to open stores in Wilton. (See Image 11.)

In August, 1900, the WLCC sent seven tons of coal to the Edison electric plant in Fargo where the coal was tested for quality. The electric company reported that lignite produced no clinkers and no black smoke. The company – which burned coal to generate electricity – found that locally mined lignite was less expensive than coal brought by train from eastern coal mines.

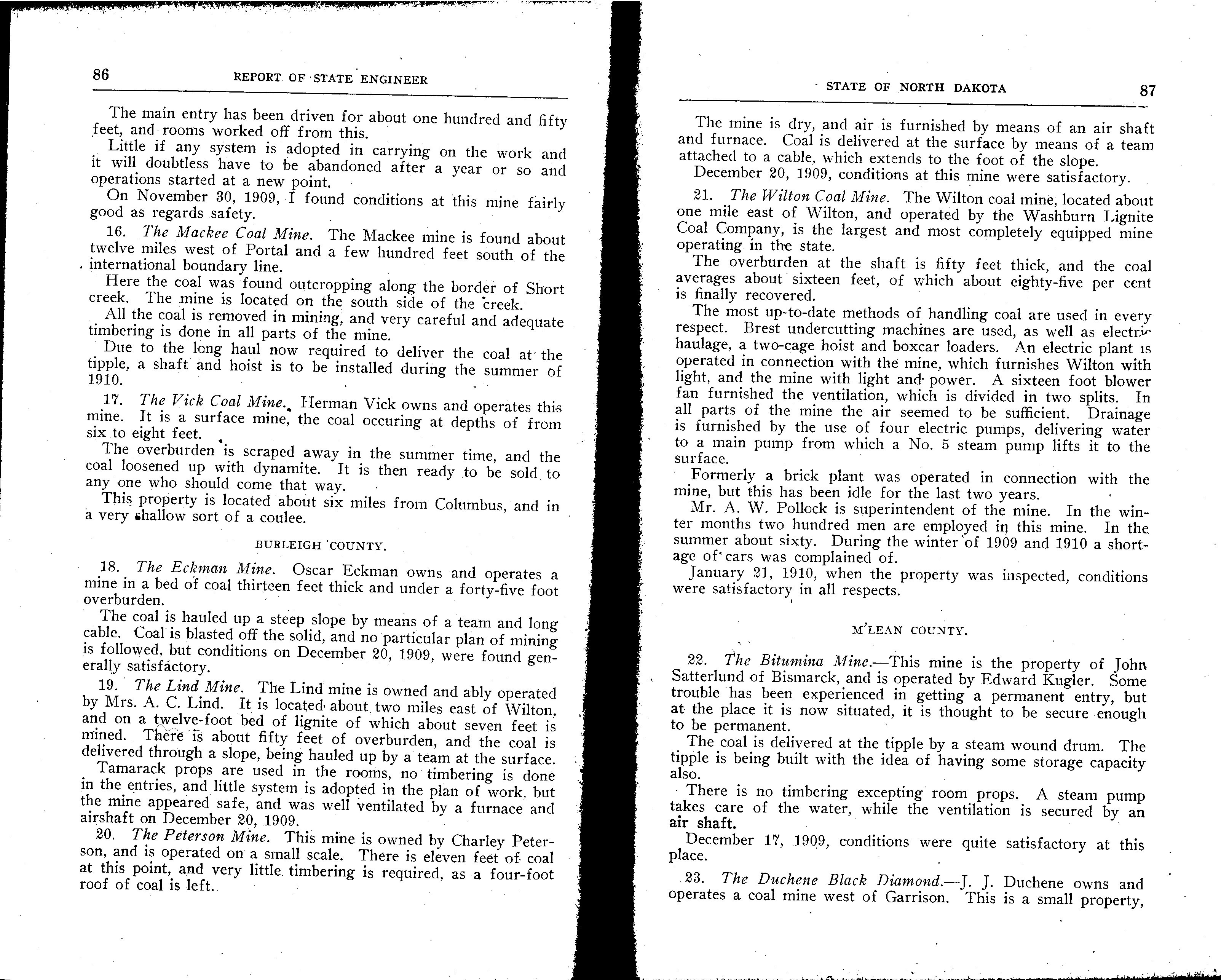

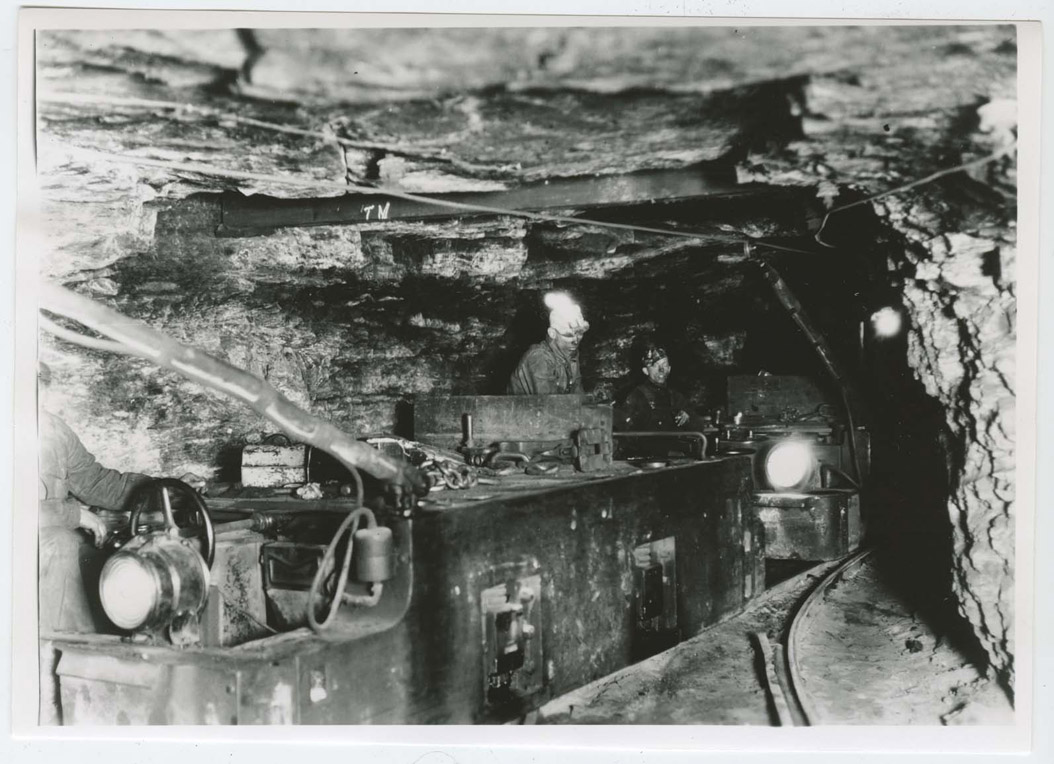

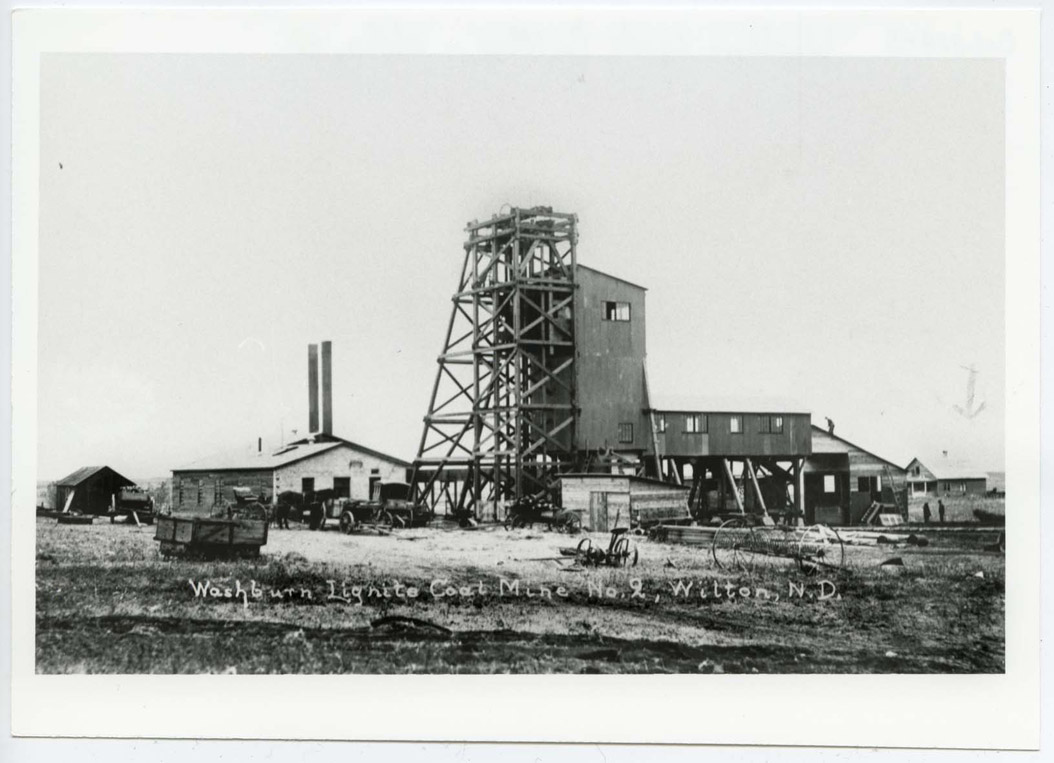

By September, 1900, the Washburn mine at Wilton was producing 50 tons of coal a day. General Washburn wanted the mine to be as modern, efficient, and safe as possible. The company installed a plant to generate electricity for the mine. Miners worked with electric machinery and had electric lighting. The generator also supplied electricity to Wilton households. (See Image 12.)

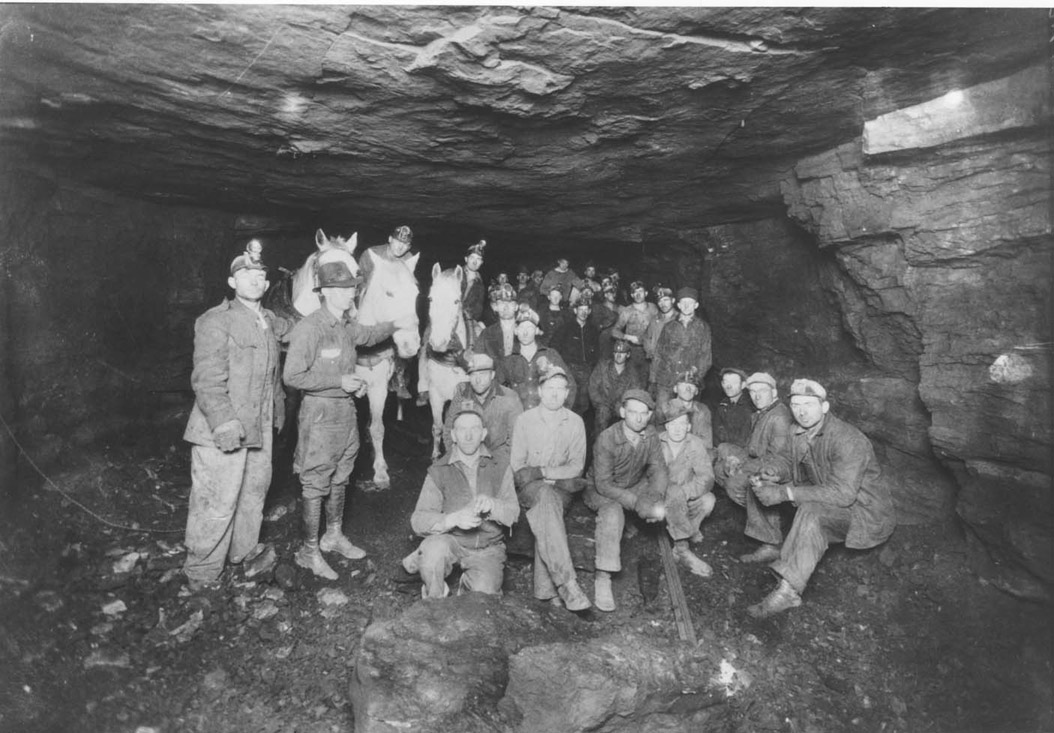

Soon, Wilton No.1 mine had two mine shafts and two air shafts. (See Document 3.) Horses or mules pulled coal cars on tracks to the surface. The company purchased mine timbers locally, so the wealth of the mine was spread throughout the community. (See Image 13.)

The mine and coal production grew quickly. By the end of 1900, miners were producing 200 tons of coal per day. The mine shafts were 300 to 400 feet long and 70 feet below the surface. The mine operated 20 hours per day, seven days a week at first. Nearly 100 men worked in the mine.

The critical season for coal mines was fall and winter. General Washburn wanted to find alternative markets for lignite coal so the mines could operate year ’round. Though lignite was not considered to be a good fuel for train engines, General Washburn tested a specially built engine with lignite coal. The train pulled 43 loaded freight cars from Bismarck to Jamestown at 20 miles per hour. The engine burned 18.5 tons of coal on this run resulting in a savings of 40% on fuel. Both the SOO Line railroad and the Northern Pacific Railway began to use lignite in their engines. (See Image 14.)

By 1903, the Washburn mine in Wilton was producing 1,000 tons of coal per day. (See Image 15.) The operation had become large enough to build two other communities, Chapin and Langhorn, where miners lived with their families.

In 1906, the mine reached a layer of clay below the coal. The Washburn Company began to make bricks, using its own lignite to fire the kilns. These bricks were used for buildings in Wilton and Bismarck, but the alkali content tended to streak the buildings. The brick factory closed in 1908.

By 1915, the mine employed 400 workers who produced 1,500 tons of coal per day. The mine had contracts to provide coal to the state capitol and state institutions, public schools, power houses, mills, and the railroad. See Coal film.

The Washburn family sold the mine in 1928. The company that bought the mine made a strip mine north of the old Wilton No. 1 and No. 2 mines. Strip mines need fewer workers to operate the big shovels and trucks on the surface. The strip mine closed in 1938. The era of coal mining in the Wilton area ended.

Why is this important? The Wilton lignite mines were the first large-scale coal mines in North Dakota. Wilton No. 1 and Wilton No. 2 were the most productive underground coal mines in the state from 1900 to 1915. Coal was an important source of fuel in a state that had few trees and little running water to generate power. Private homeowners purchased coal to heat their homes. North Dakota lignite coal was a significant source of fuel for railroads and power companies. In 1919, a mining engineer named F. L. Anders predicted that

a series of great power plants will be scattered over the valley of the Missouri River, linked together by a circuit of high tension wires and sending energy to many cities and railroad systems of the northwest. - Wilton News, February 17, 1919

Mr. Anders was correct. The Wilton Mine pointed the way to North Dakota’s energy-rich future.

A Coal Miner’s Life and Work

In 1900, most of the men working for the Washburn Lignite Coal Company (WLCC). were probably farmers looking for extra “off-season” work. By September, 1900, there were 70 men divided into two crews. Each man worked a 10 hour shift. (See Image 16.)

Single men and those working far from home lived in The Beanery, a boarding house owned by the WLCC in Wilton. The Beanery was a two-story building with 20 sleeping rooms. Local girls and women cooked and cleaned for the miners in the Beanery. Girls considered a job in the Beanery to be a good job because it was “good husband hunting ground.” The girls knew that a miner made good wages. If he also had a farm, he would be a hard-working man who would support his family well.

Many of the miners were local farmers. Some were immigrants who were working the mines until their families could join them. Miners came from Ukraine, Germany, Sweden, Norway, and the United States.

Miners rode the train from Wilton to the mines a couple of miles from town. Though they paid $5 a month for the train rides, the train was warmer and safer than walking that distance in the winter. (See Image 17.)

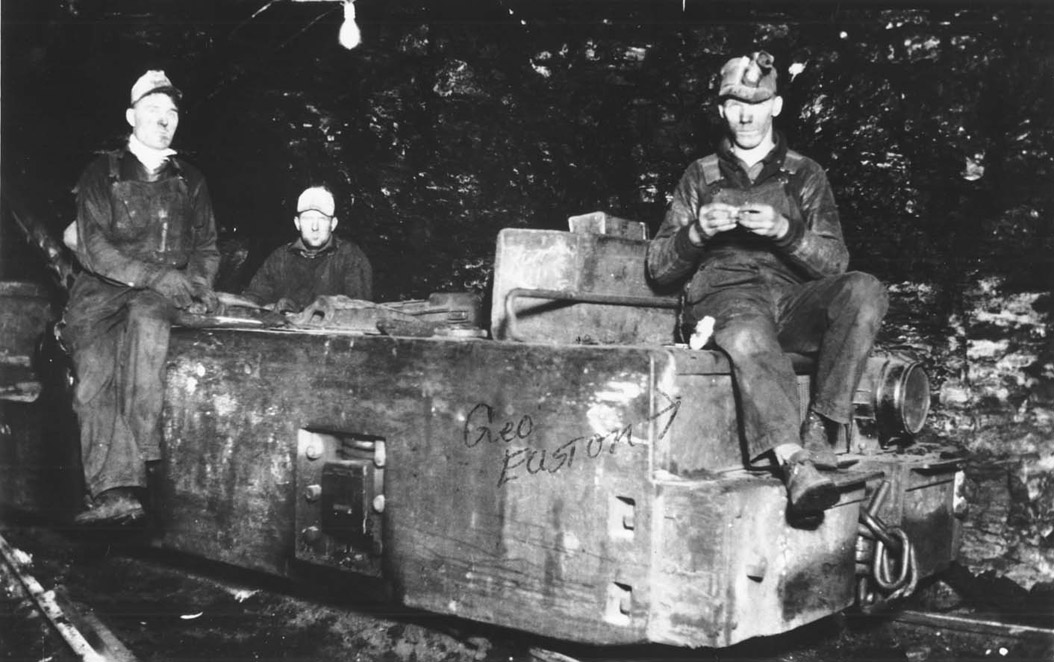

Miners worked with electrically powered equipment in the Wilton No. 1 and No. 2 mines. Electric cutters opened a coal seam. Electric drills bored holes in the seams at intervals. Dynamite was placed in the holes. When the dynamite exploded, the miners picked up the loosened coal and placed it in the coal cars. The miners depended on two electric fans to bring fresh air into the mine shafts. (See Image 18.)

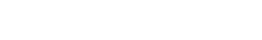

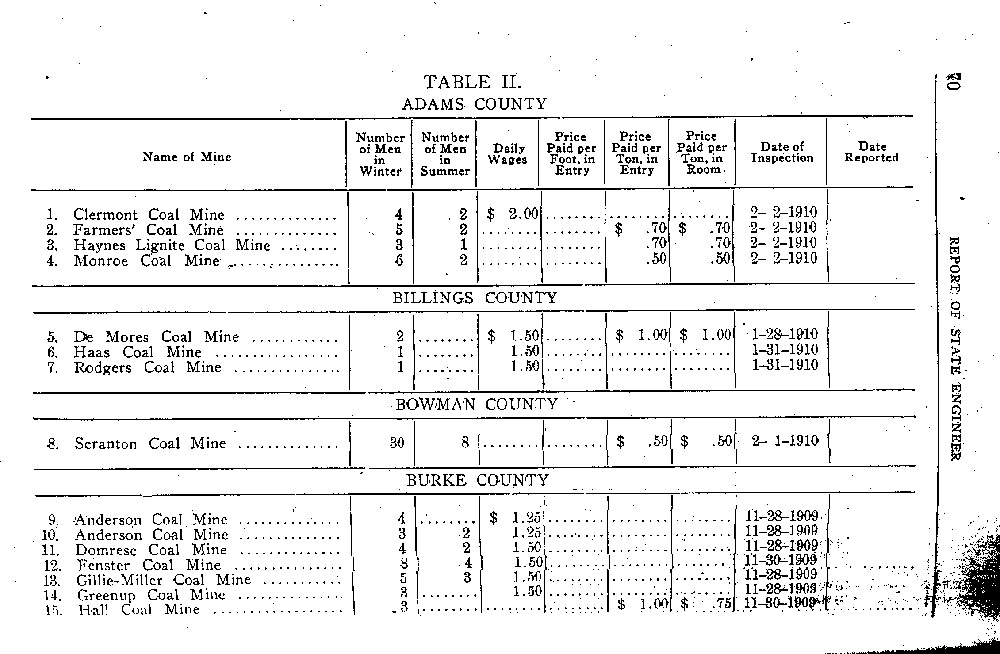

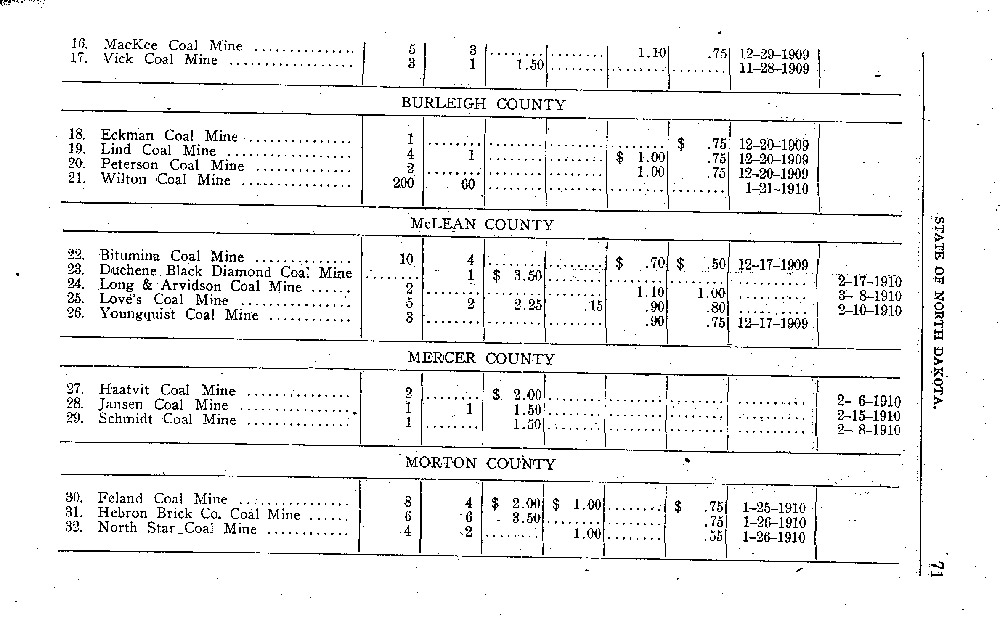

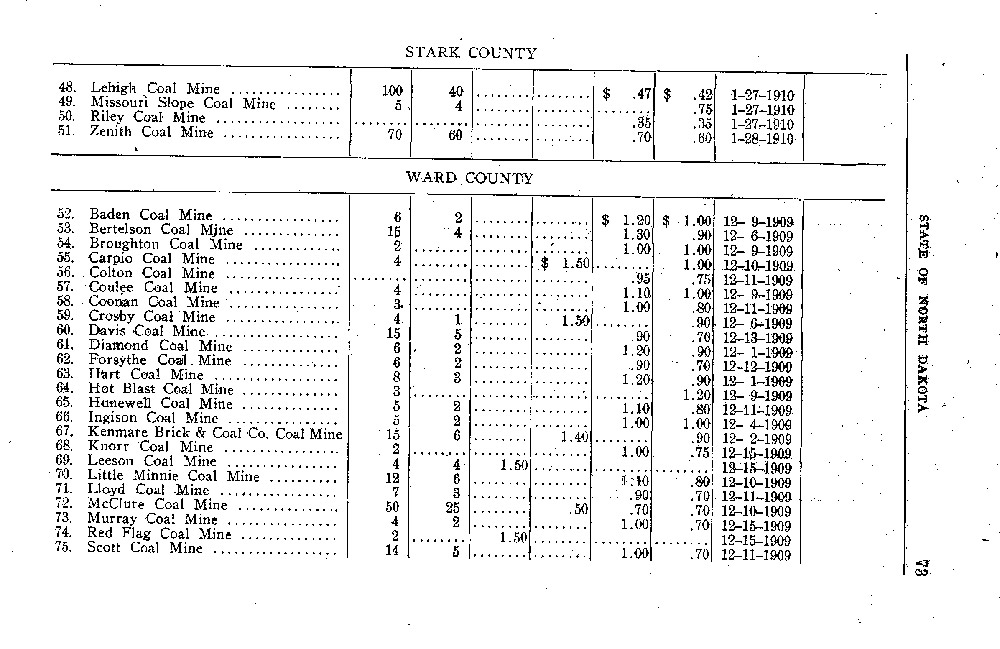

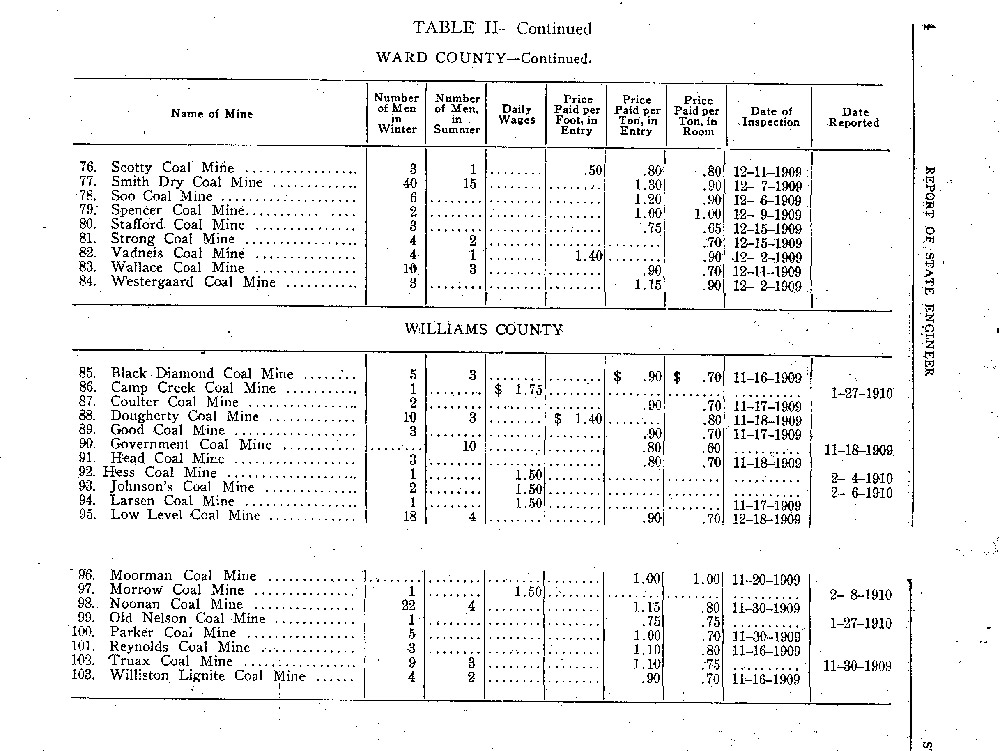

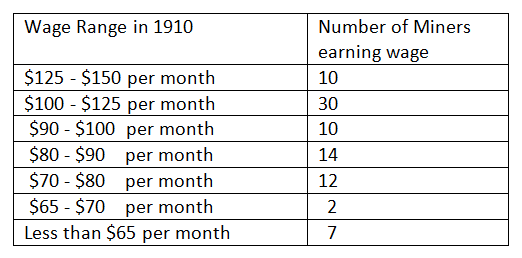

In 1903, the mines were producing 1,000 tons of coal a day. The miners were paid 30 cents per ton for picking coal from the walls. If they worked to make the entrance secure, they were paid 35 cents per ton. (See Chart 1) Wages at the Wilton mines were higher than the national average for miners because other jobs such as harvest work or farming competed with mine jobs. The company had to pay high wages to keep men at work in the mines. (See Document 4.)

The company built two more towns, Chapin and Langhorn, for miners by 1907. These towns had houses for miners with families. There were schools at Chapin and Wilton.

For the most part, the WLCC was a good company to work for. Electricity brought light and labor-saving equipment into the mine shafts. Each family man received a turkey at Thanksgiving. General Washburn gave miners and their families a holiday dinner at Christmastime. Children received Christmas treats. The company cut and stored ice each winter for the employees to use in the summer. General Washburn also brought a medical doctor to Wilton in 1901. Dr. R. C. Thompson tended miners and their families. Each miner paid $1 per week for Dr. Thompson’s services. When small pox threatened the miners’ families, General Washburn brought a team of doctors from Bismarck to vaccinate all the miners and their families.

The WLCC also provided miners with hot showers and a changing room. Each miner had a locker in the changing room. All of these benefits, part of a system called paternalism, were designed to prevent miners from joining a labor union.

On payday, miners relaxed by playing cards, shopping, and, of course, drinking. Though North Dakota was a “dry” state (the manufacture and sale of alcohol was prohibited), there was a lot of home-brewed beer in Wilton. The Wilton police were alert for fights and problems caused by drunkenness.

Though the Washburn coal mines had some labor conflict, both mines and miners prospered. The Wilton miners were among the best paid workers in the state of North Dakota. By 1920, many miners owned automobiles. They traveled to work in their cars, so the mine train was discontinued.

Why is this important? Working in the mines was not a perfect job. It was dangerous. The first few years, work was available only in the winter. However, a mine job paid well, and many miners considered these good jobs. A farmer might make more money when crops were good and crop prices were high, but the Wilton mines employed men steadily at good wages for more than 25 years. Farmers who took advantage of seasonal work in the mines earned a second income that helped their families survive the bad years. The coal mines helped to diversify the state’s economy and strengthen its industrial growth.

Coal Mine Safety

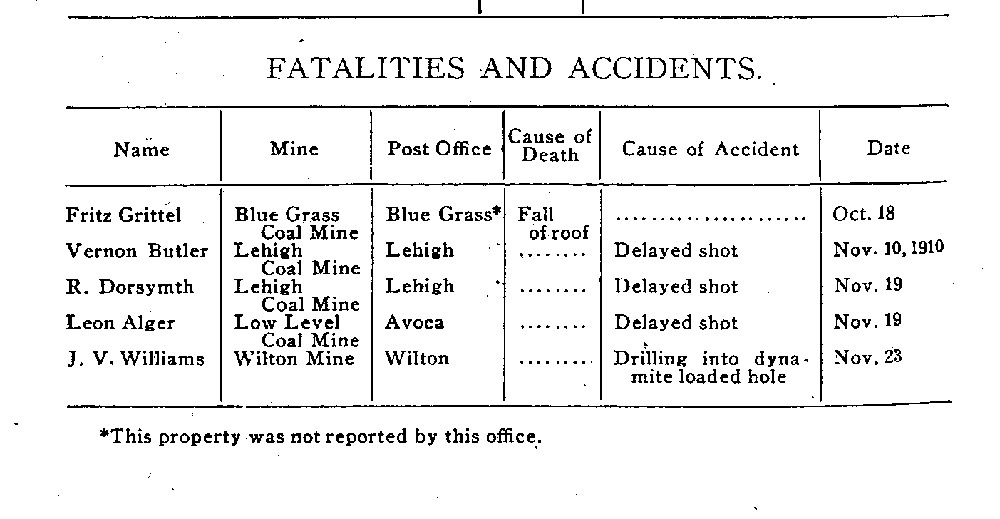

The state mine inspector considered the Washburn Lignite Coal Company (WLCC) mines at Wilton to be relatively safe. Proper ventilation and electric machinery promoted safe working conditions. Mining, however, was extremely dangerous work, and the WLCC had its share of accidents and health concerns. (See Document 5.)

When Wilton No. 2 opened, it had water seepage in the lower tunnels. Miners had to work in water up to their knees. Some workers refused to work in such conditions. Others accepted a 4 cent per ton incentive and continued to work. These miners left the mine soaking wet at the end of their shift during winter’s cold. The miners changed and showered in a washroom some distance away, and they were quite cold by the time they got to the showers. The company, however, had hot showers available to warm the miners before they went home.

In spite of mine manager Walter Macomber’s efforts to make the mine safe, some miners died in accidents. Especially dangerous was the job of knocking coal from the tunnel ceiling. In 1913 and 1917, miners died in underground accidents.

Between 1913 and 1917, the mine reported 101 non-fatal accidents. These injuries varied from minor to very serious. One man lost an eye when he was hit in the eye by a broken whip. A mule trainer’s whip broke while he was working with a mule. The broken piece flew across the room and hit the miner in the face.

Dr. Thompson ran a small hospital for the miners in Wilton, but men with serious injuries were transported to a hospital in Bismarck. (See Image 19.)

Why is this important? Miners depended on the mine owners and managers to maintain high safety standards. Those who worked in small mines were especially likely to work in unsafe conditions. The miners at the Washburn mines at Wilton tended to look after each other’s needs. When they felt the conditions were unsafe, such as when they had to work in water, they forced the company to respond to their needs by threatening to cease work. Safety was a major issue for miners’ unions. By making the mines safe, the owners could avoid unionization of the workers.

The Strike of 1919.

The fall of 1919 was full of trouble for Americans. There were many political conflicts and the farm economy at the end of World War I was failing. Coal supplies throughout the United States were low. In Duluth, Minnesota, the coal shipped for distribution to North Dakota had been slowed by a dock workers' strikeA strike takes place when a company’s workers decide to stop working because they think something is wrong. It might be that they have low wages, unsafe working conditions, or they want to organize a union. By walking off their jobs, the workers take a great risk. The company might hire other people to do the work. The workers might lose pay while they are not working and still not get what they want from the company. The Union usually has a “strike fund” which helps miners pay their bills while they are on strike. When workers form a union, the union leaders try to negotiate conditions that will satisfy the workers’ needs. Sometimes the unions are successful, but sometimes they fail to change working conditions. in the summer. No one knew in October that winter would come early with a major blizzard.

The United Mine Workers Union (UMW), a national union for all miners, called for a strike in bituminous (hard coal) mines. Unionized miners all over the country also walked out in support of their union brothers; they all wanted a new contract. It was a good time for a coal strike. The miners had an advantage in negotiations with winter coming. The Union, led by the powerful John L. Lewis, wanted higher wages for miners. The strike was to start on November 1, 1919.

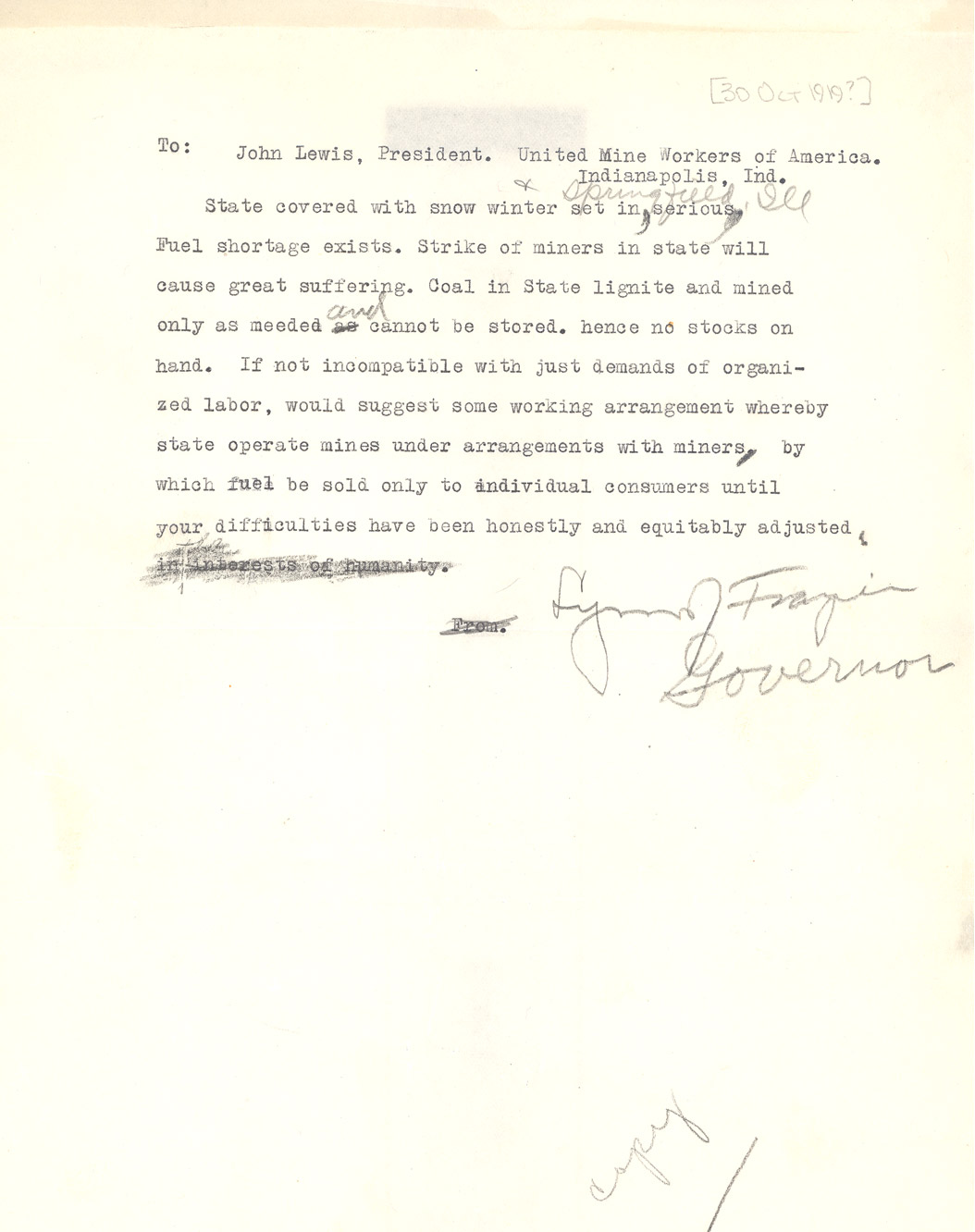

The Governor of North Dakota was Lynn Frazier, a member of the Nonpartisan League. (See Image 20.) Frazier was concerned because the supplies of local lignite and imported hard coals were low. There were 34 unionized coal mines in North Dakota, many of them serving cities such as Williston or Minot.

Frazier asked the UMW to allow North Dakota’s coal mines to continue operating under a “working arrangement.” (See Document 6.) Frazier wanted the miners to keep bringing coal to the surface while the union negotiated a new contract. In return, the North Dakota’s unionized lignite miners would be covered under the same contract as the bituminous coal miners. Governor Frazier believed that the miners’ request for higher pay was justified.

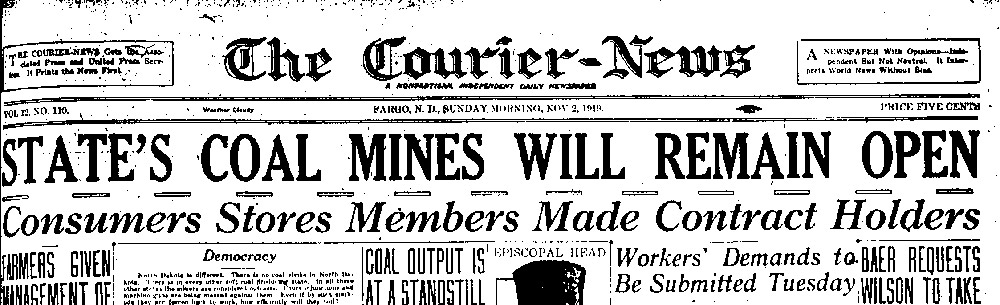

Frazier was successful. The strike was cancelled in North Dakota and the miners kept on working while their representatives negotiated a new contract. The regional UMW president, Henry Drennan of Billings, Montana, traveled to Bismarck to begin talking with the mine owners and the miners about ways to resolve the miners’ demands.

However, negotiations ended on Friday, November 8. Several problems prevented Governor Frazier, the mine owners, and the miners from reaching an agreement:

- North Dakota lignite miners asked for the same wage increase (60%) that bituminous miners requested

- Lignite miners wanted their wage increase to go into the national strike fund to help striking miners elsewhere

- Mine owners did not want to pay higher wages that would contribute to a strike fund because the federal government opposed any move that would extend the strike

- Governor Frazier thought the miners were reasonable, but he thought the mine owners were uncooperative.

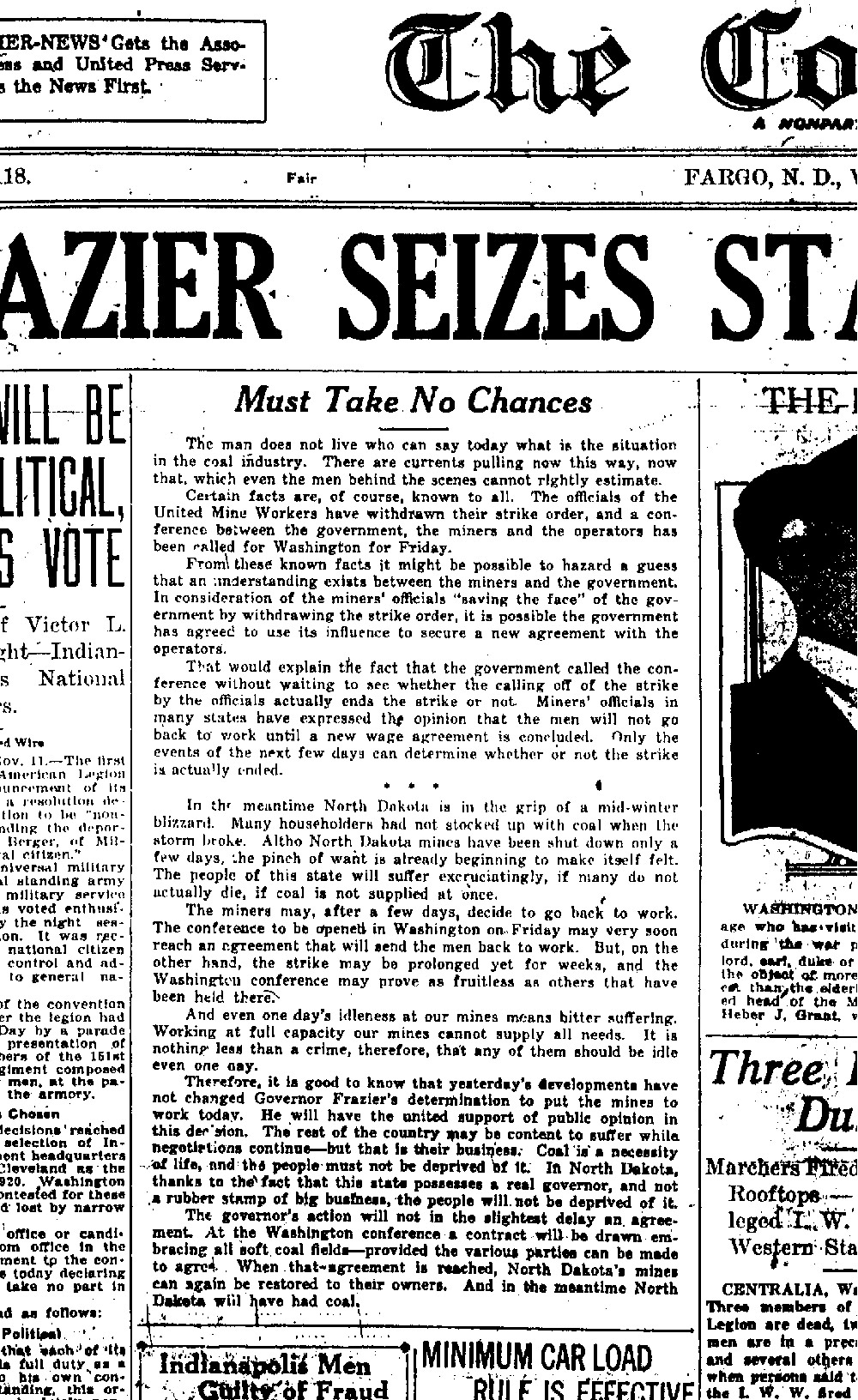

When negotiations broke down, Mr. Drennan ordered a strike to begin immediately. (See Document 7.) A blizzard roared into the state on the same day and continued for several days. Towns and families already short of fuel began to worry about how they would keep warm.

On Monday, November 10, Governor Frazier re-opened the mines under state control “in behalf of the public, with justice and fairness to all, until the present emergency shall have passed.” He declared martial lawMartial law can be declared by a state governor or the president. It usually means that the government will use military force to uphold civil and criminal laws. It might also mean that certain rights are suspended. In North Dakota, Governor Frazier used martial law to allow the “home guard,” or National Guard troops, to keep the mines open and running. and sent soldiers to manage the mines. The miners were supposed to return to work on Wednesday, November 12.

Mine owners protested, and several of them went to court to get an injunction (a court order to stop) against the state. In spite of the owners’ protests, the mines re-opened peacefully.

Three different judges heard the cases. Judges Nuessle and Robinson ruled in favor of the coal companies; Judge Amidon supported the state. All of their rulings were temporary. The state Supreme Court made the final decision on November 21. The court decided that the state had to return the mines to the owners.

The nationwide strike ended on November 11, 1919. On November 22, the Washburn Lignite Coal Company, the largest mine in the state, regained control of its mines. North Dakota mine owners agreed to give miners the national raise of 14 per cent. The miners returned to work. When the tipple of Wilton Mine No. 2 caught on fire a few days later, the miners fought hard to prevent the fire from dropping down into the tunnels. A few weeks later, Wilton No. 2, was back in production.

By the end of December, coal supplies and coal production in North Dakota were nearly back to normal.

Why is this important? Though North Dakota’s lignite miners were generally satisfied with their contracts, they went out on strike in support of miners in other states. They considered the other miners to be “brothers.” The mine owners wanted to continue to operate their mines in their own way. The critical issue for the governor was the supply of coal to heat homes and businesses as winter approached. The strike happened because none of the three parties was willing to compromise. Some North Dakota residents also worried that since state government was controlled by the Nonpartisan League, it would try to gain state ownership of the mines rather than return the mines to the owners. In the end, the mines returned to their normal status, the workers returned to their jobs, and Governor Frazier succeeded in ensuring a good supply of coal for the winter of 1920.