Missionaries came to the northern Great Plains as early as 1818. After 1865, missionaries of both Catholic and Protestant faiths brought Christian theology and ritual to all of the American Indian tribes in the region. Missionaries willingly served this remote region in order to convert Indians from their traditional spirituality to European American Christianity.

Missionaries also came to serve Anglo-American Christian settlers’ communities. Itinerant (traveling) ministers traveled from house to house, depending on settlers to feed and house them. (See Document 7) When they arrived in an area where there were enough people, they performed baptisms and weddings. (See Document 8) Some couples set up household and started to raise children before a traveling minister showed up to marry them and baptize their children.

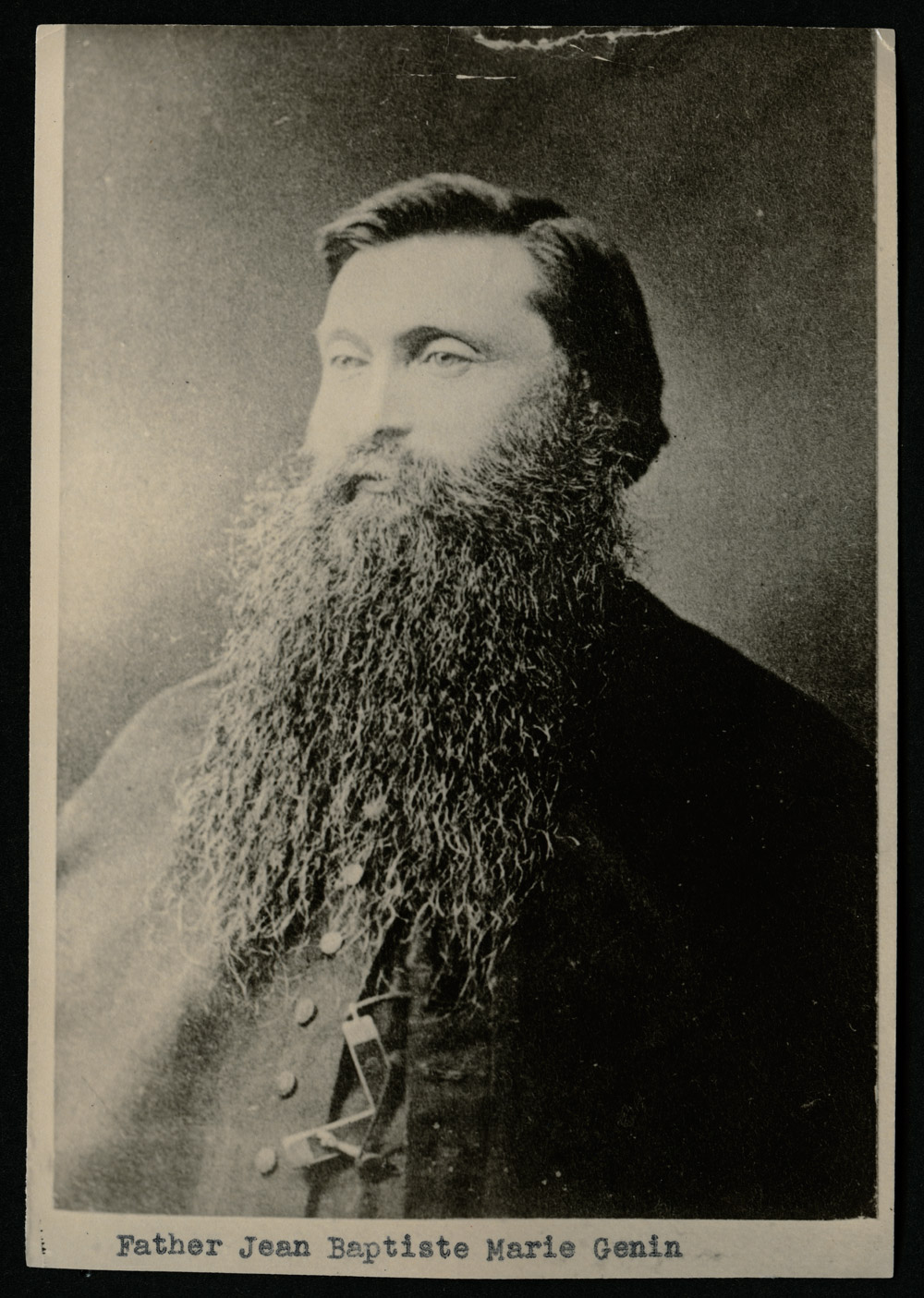

Catholic priests like Father J. B. M. Genin served both American Indian tribes and small town parishes. (See Image 11) Genin helped to establish Catholic churches in towns along the Northern Pacific rail line including Bismarck. He had already spent many years as a missionary among the Turtle Mountain Chippewa and would spend many more years working among the Lakota. He was adopted into the Lakota family of Black Moon.

In the 1870s, President Grant established a new Indian policy called the Peace Policy. Under this plan, American Christian churches that were interested in participating were given responsibility for a reservation. The Catholic Church was already well-established at Fort Totten. A Catholic mission was also established at Fort Yates (which is today the capital of Standing Rock Reservation). In addition, Reverend Aaron M. Beede established an Episcopalian mission at Standing Rock. Beede also served missions among the Chippewa of Turtle Mountain. There were both a Catholic mission and a Congregational mission at Fort Berthold.

Missionaries brought a comprehensive program to reservations. They set up both schools and churches. Missionaries encouraged parents to enroll their children in the mission school, and many parents did so to keep their children at home on the reservation rather than send them to distant boarding school.

Missionaries often had a hard time getting adults on reservations to attend church services on Sundays. Little by little, adults began to attend services, but many adults still resisted the missionaries’ pressure to convert to Christianity. Missionaries wanted converts to give up all aspects of their traditional culture. They were to wear “white men’s clothes” such as pants, shirts, and dresses made of cloth. They were to live in houses made of wood. Most importantly, they were supposed to give up all expressions of traditional spirituality including dancing. Many Catholic mission priests accepted a mixture of Christianity with the traditions of the people they served. Protestant missionaries were less flexible. Most Protestant missionaries believed that Indians could not fully adopt Christianity without also adopting Anglo-American cultural characteristics.

Ironically, while missionaries were trying to eliminate all traces of spiritual traditions among American Indians, they also took on the task of preserving a record of the culture they were trying to erase. Missionaries recorded traditions and tribal history, preserved artifacts (such as handmade moccasins), and arranged for anthropologists to study Indian culture. In mission schools, children were encouraged to learn some traditional skills such as beadwork. Missionaries, more than federal agents, were motivated to preserve American Indian cultures while they were at the same time determined to destroy them.

Why is this important?Missions provided an important service to Anglo-American settlers in the late 19th century. As the settlers built homes and began to create communities with their neighbors they sought ways of establishing congregations that would provide spiritual relief during the difficult years of settlement. These Christian communities are still an important part of North Dakota’s culture today.

Though missions were often welcomed on reservations for the material advances they brought, the practice of Christianity often meant further loss of traditional culture. However, Christianity was accepted by many American Indians. Their new faith filled a void left by the loss of territory, homes, families, and traditional ceremonies.

Source: for more on Father J. B. M. Genin: Linda W. Slaughter, “Leaves from Northwestern History,” Collections of the State Historical Society of North Dakota vol. 1 (1906): 247-249.

Charles Lemon Hall and the Congregational Mission at Fort Berthold

In 1876, Charles Lemon Hall along with his wife, arrived at Fort Berthold Reservation. They set out quickly to put up a building that served as mission, church, and school. Over the next 50 years, Reverend Hall built more buildings and with his wife and children conducted an active Congregational mission on the reservation. (See Image 12)

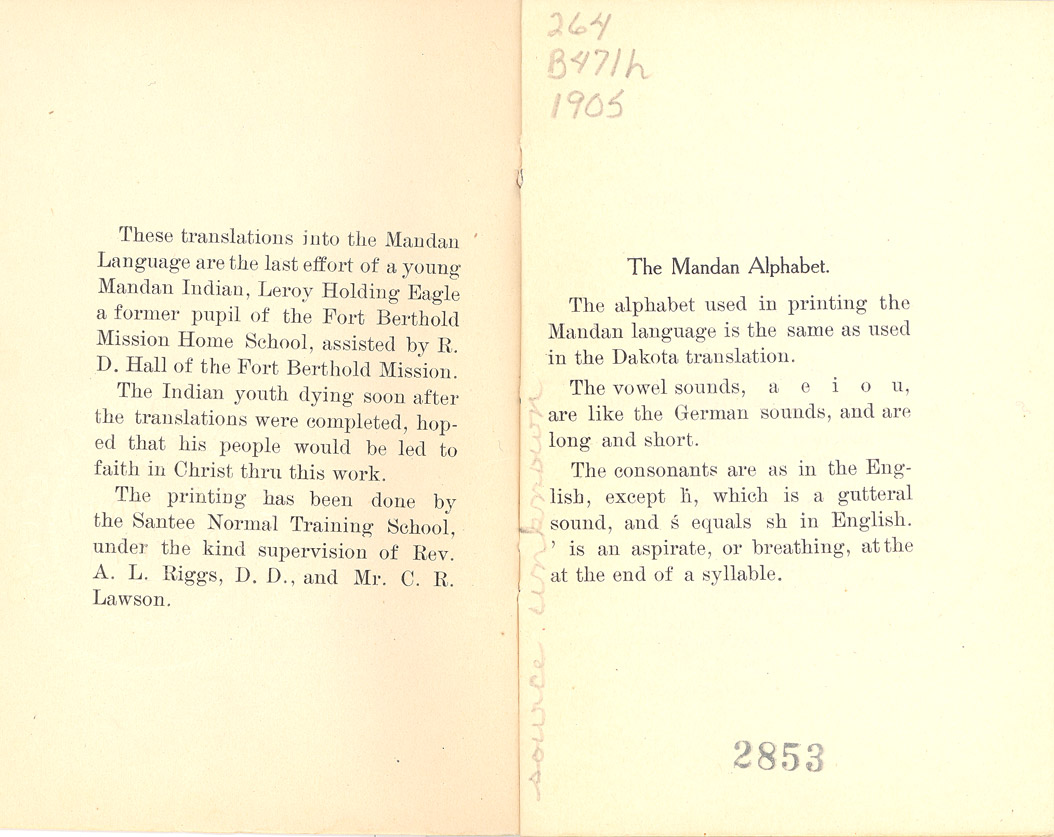

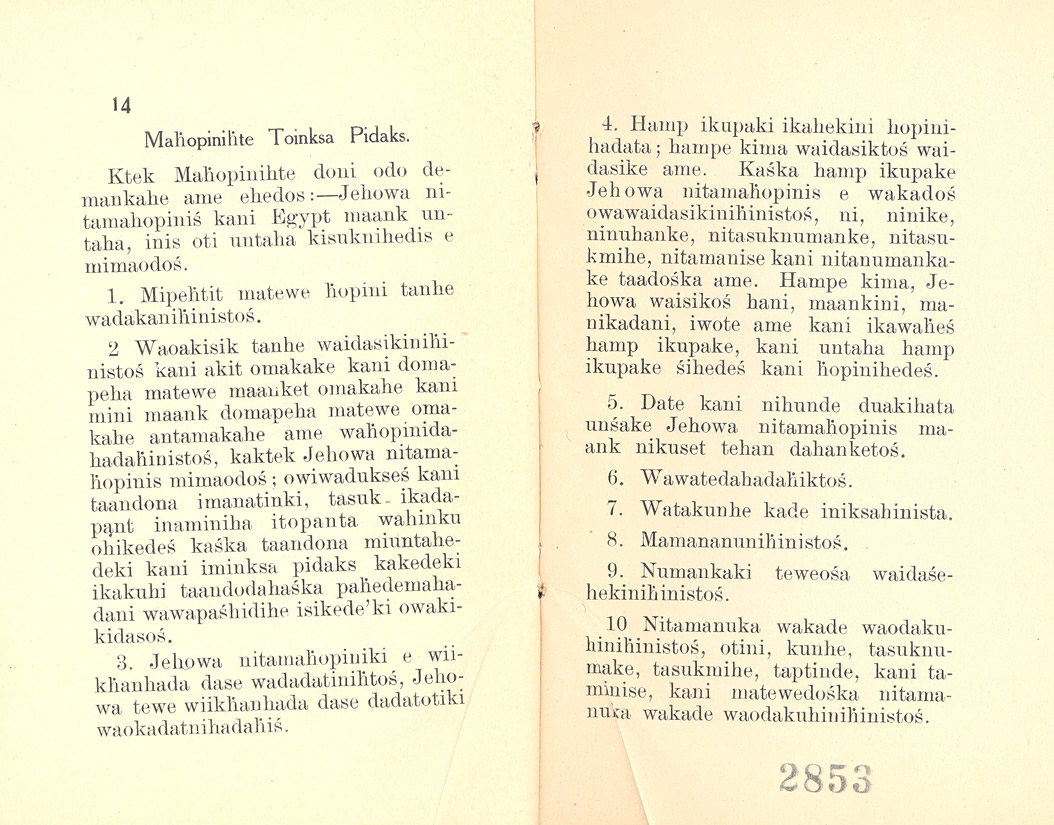

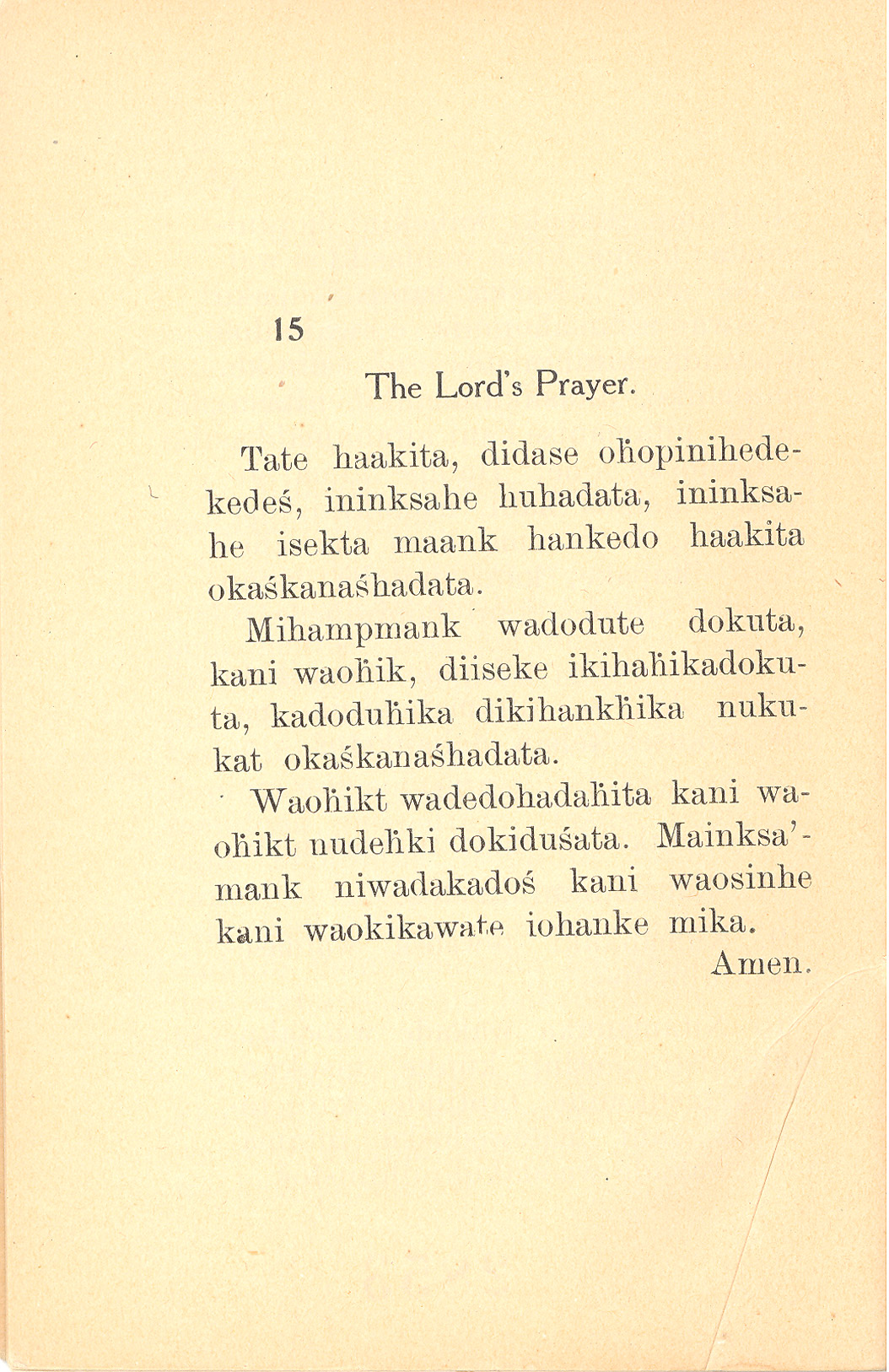

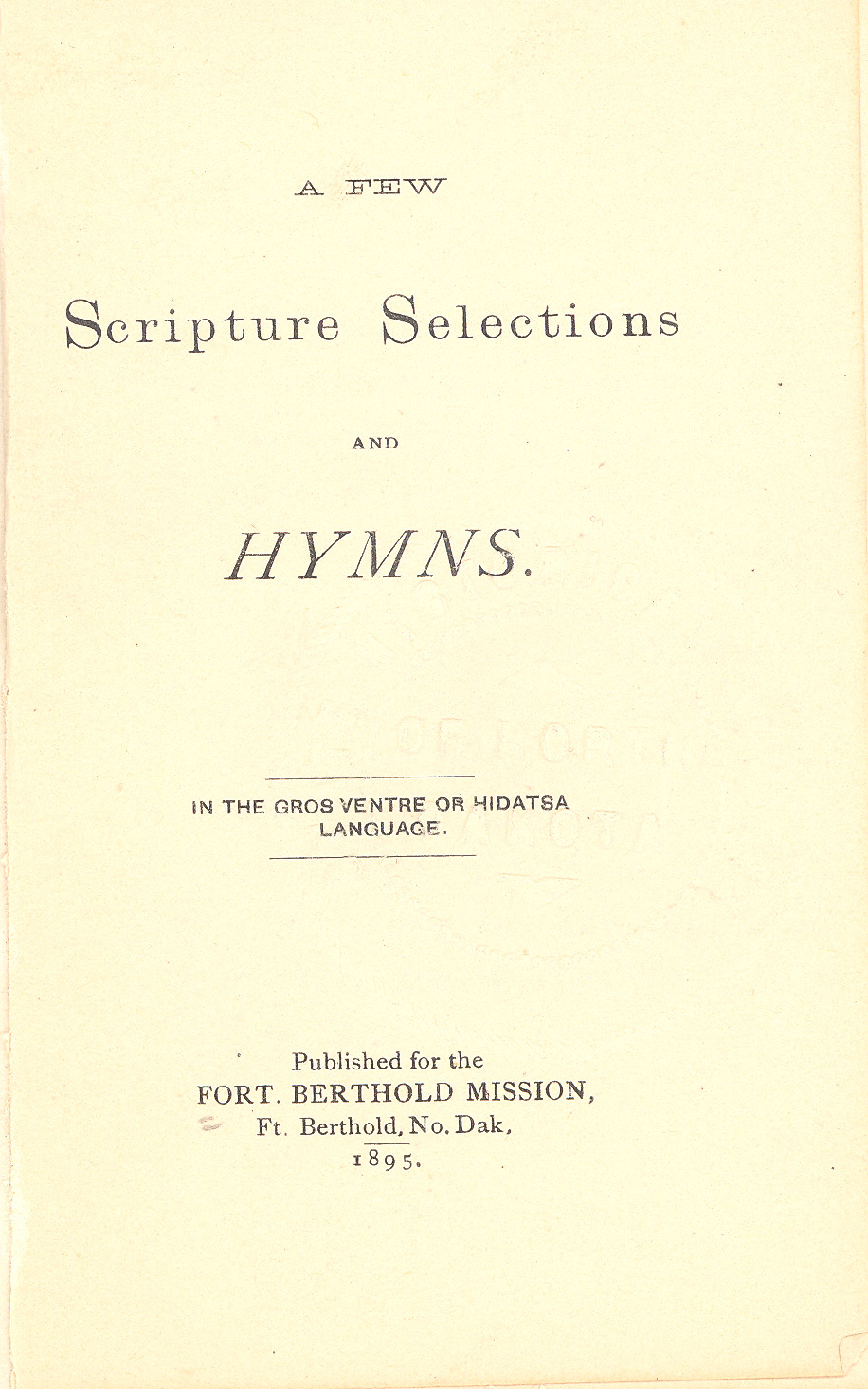

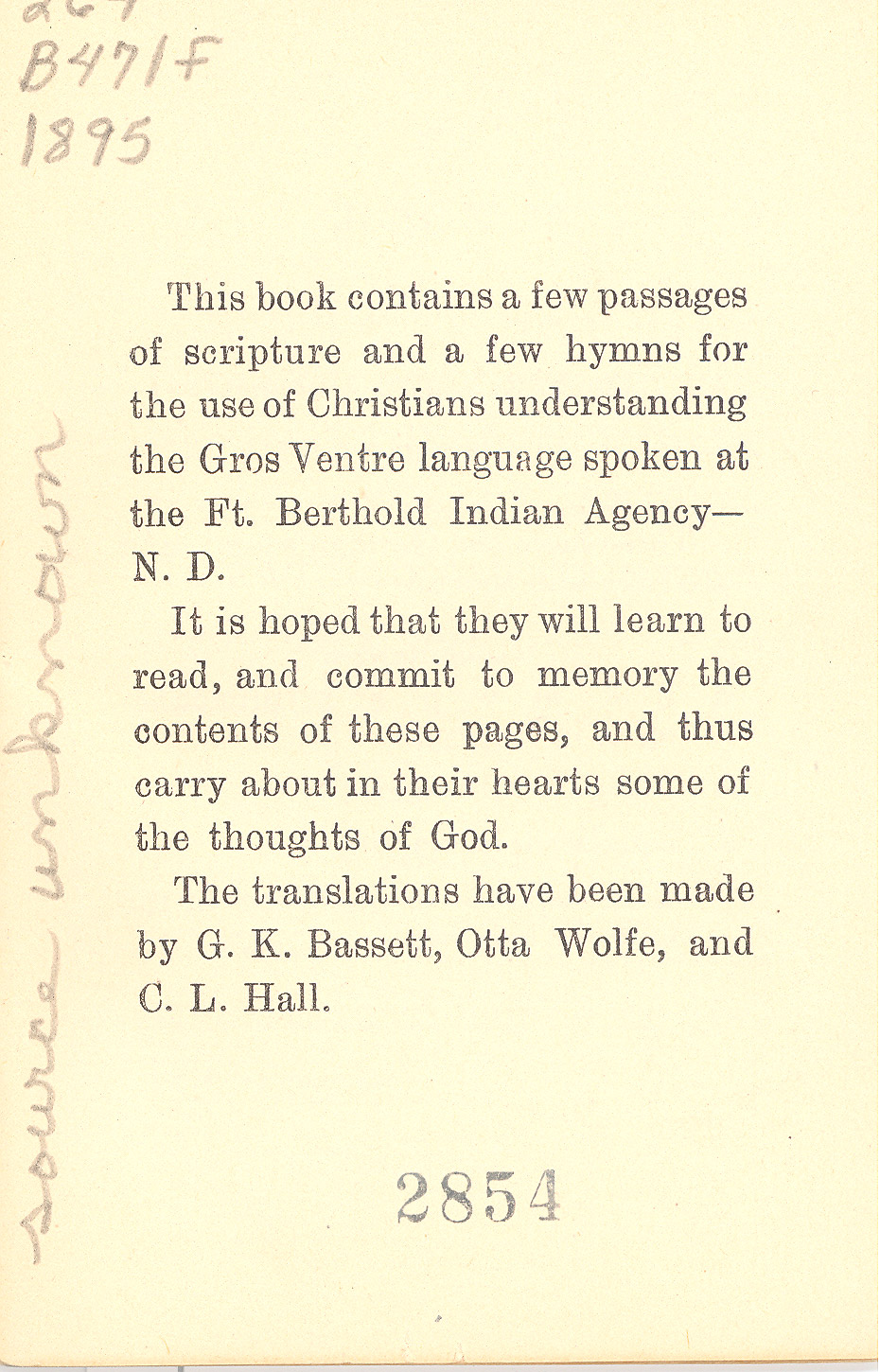

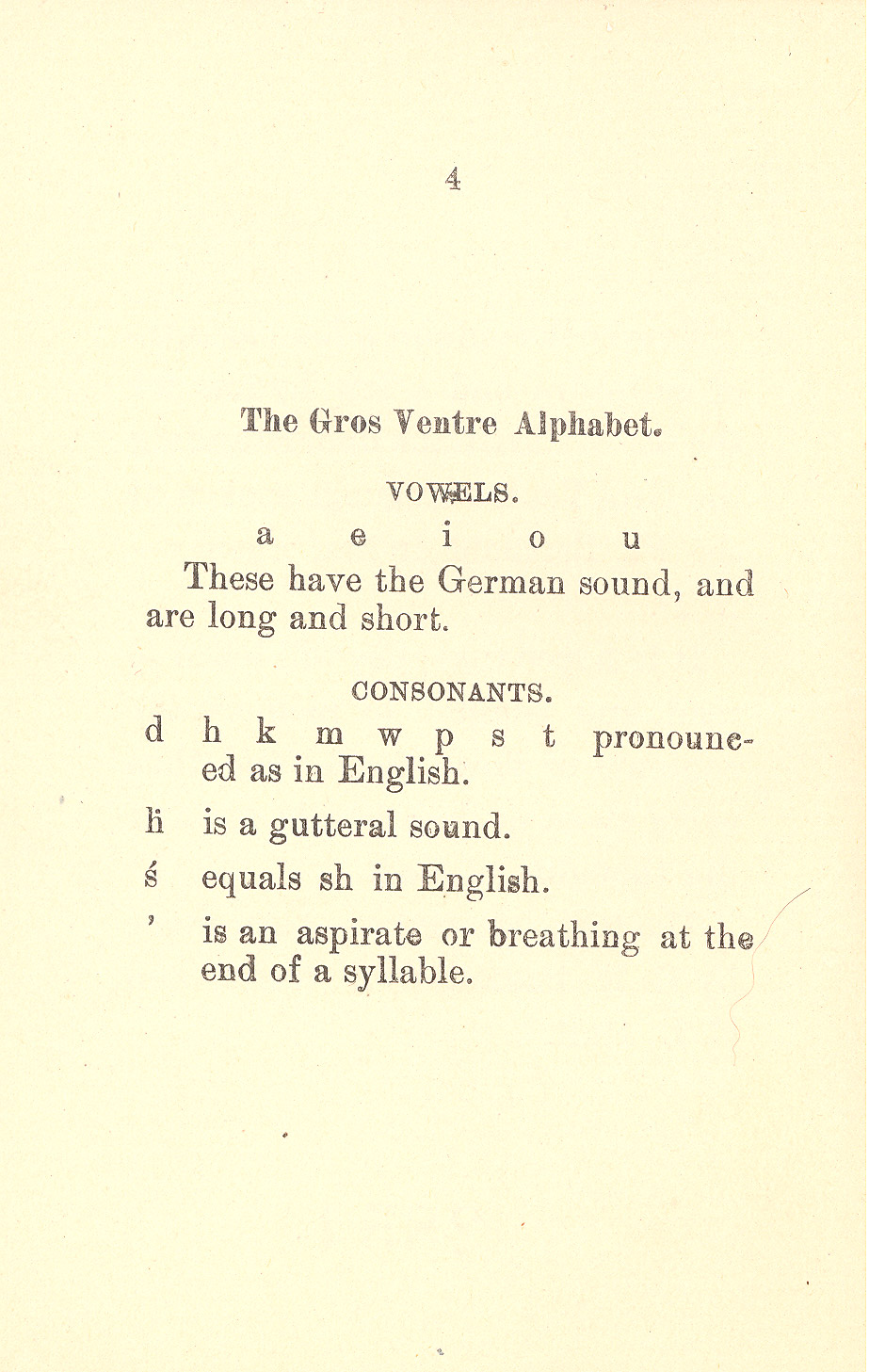

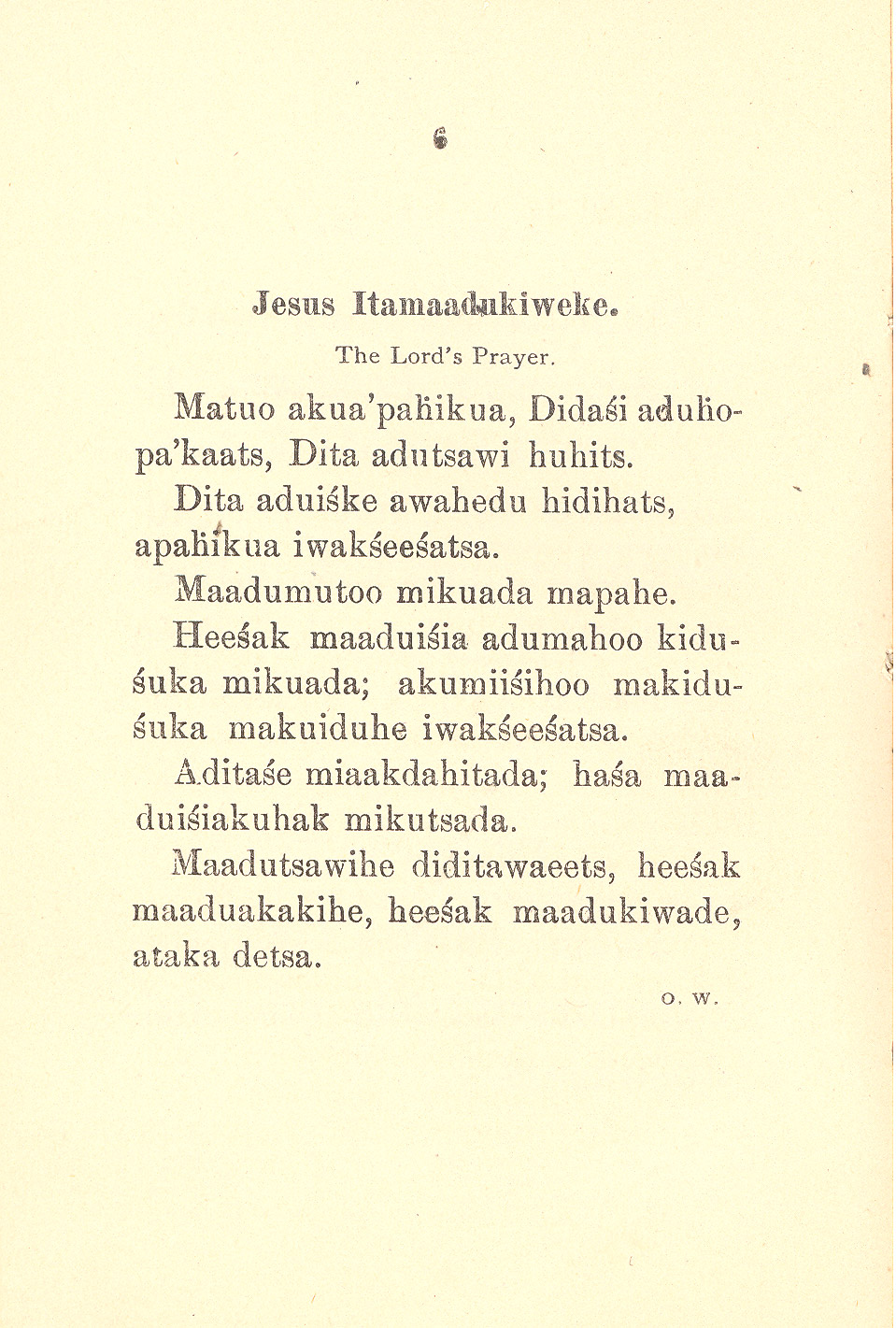

It was slow work. It took 11 years to make the first conversion. By 1889, 13 years after he arrived, Hall had converted six men and women to Christianity. Twenty-four children attended his school. The Mandans, Hidatsas, and Arikaras who lived at Fort Berthold had also had a strong effect on Hall. Hall and members of his family learned to speak Dakota, Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara. Hall compiled Mandan and Hidatsa dictionaries so that he could translate scriptures, hymns, and prayers into local languages. (See Document 4)

For Hall, and many other missionaries, Christianity and Anglo-American culture were inseparable. He insisted that converts leave their other spiritual habits to become Christians, but he also demanded that men cut their long hair, that people wear clothes similar to those of the missionaries and agents, and that they destroy all the symbols of old ways including buffalo robes and ceremonial dances. The Reverend Hall did not compromise.

One of Hall’s first converts, Poor Wolf, had always been interested in religion. He had accepted many of the changes that came with life on the reservation. He had given up hunting and fishing; he accepted the rule of law as established by federal government; he had given up warfare and horse-stealing. But he did not want to give up “the old Indian songs which are a part of the life of our people.” However, with his daughters’ help, Poor Wolf accepted Hall’s religion. (See image 13)

Others were willing to discuss religion with Hall, but felt that the cost of Hall’s version of Christianity was too high. (See Image 14) Hall asked the people to be charitable and generous which were Christian qualities, and also part of the cultural tradition of the Hidatsas. However, Hall believed that Hidatsa charity was too extreme. The gift-giving and distribution of food and clothing among the Hidatsas was, in Hall’s mind, a barbaric custom. Hall wanted each family to provide their own food and not to depend on the sharing of food as was common among those who hunted bison and raised vegetables in gardens. It was difficult for Hidatsas to understand the fine distinctions between Christian charity and Hidatsa charity.

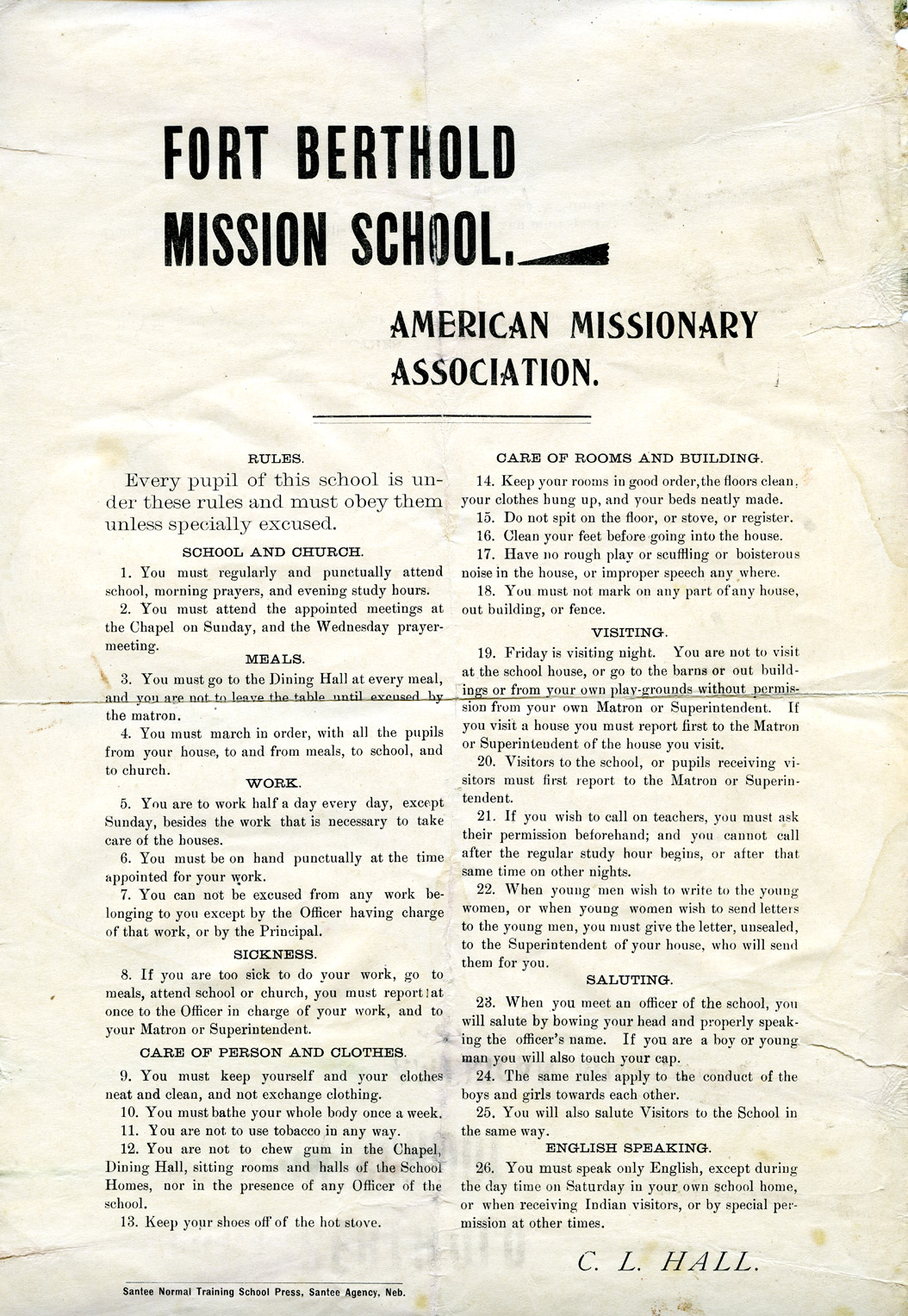

At the mission school, Hall encouraged student attendance with free meals once a week. Some students attended part-time. Edward Goodbird went to mission school in the morning, but in the afternoons he played with his friends. Those who attended school had strict rules to follow. (See Document 5) They had to speak English, salute officers of the school, and attend prayer services.

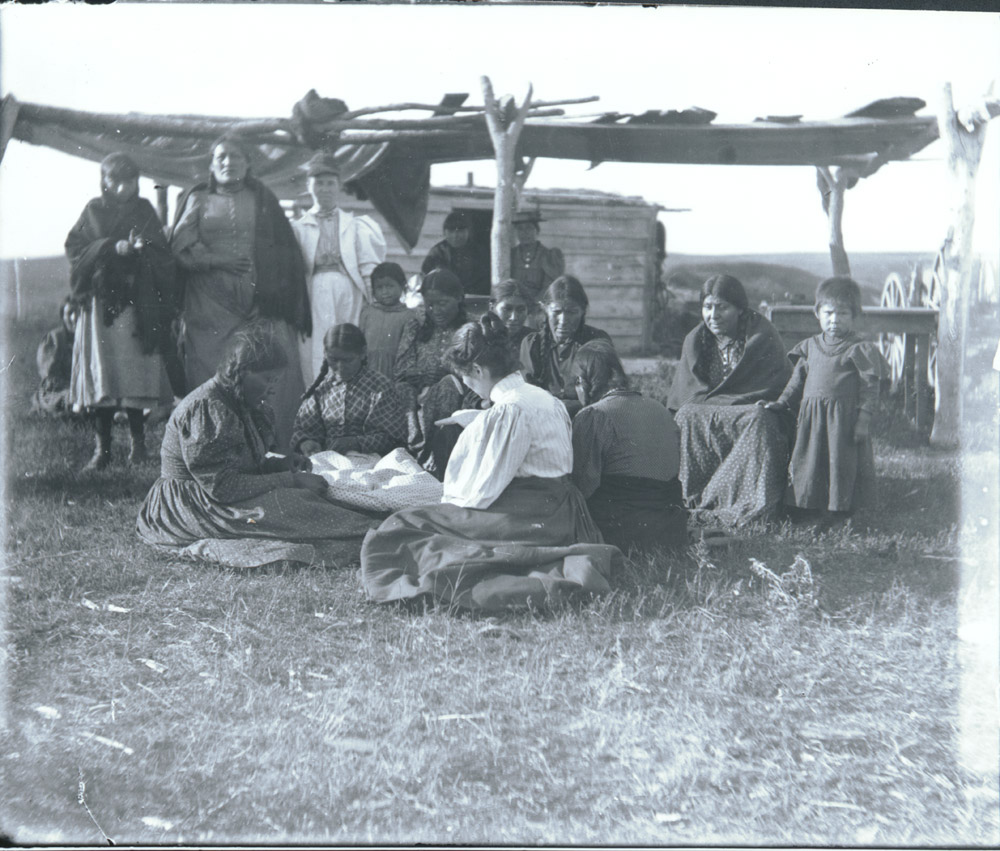

Women were brought under the influence of the mission in sewing circles. Once a week, women met with Mrs. Hall and her daughter to sew and mend. (See Image 15) The women were given cloth, thread, needles, and thimbles. After sewing for two hours, they enjoyed coffee and tea. The Indian women talked and laughed among themselves, leaving Mrs. Hall wondering if their jokes were on her.

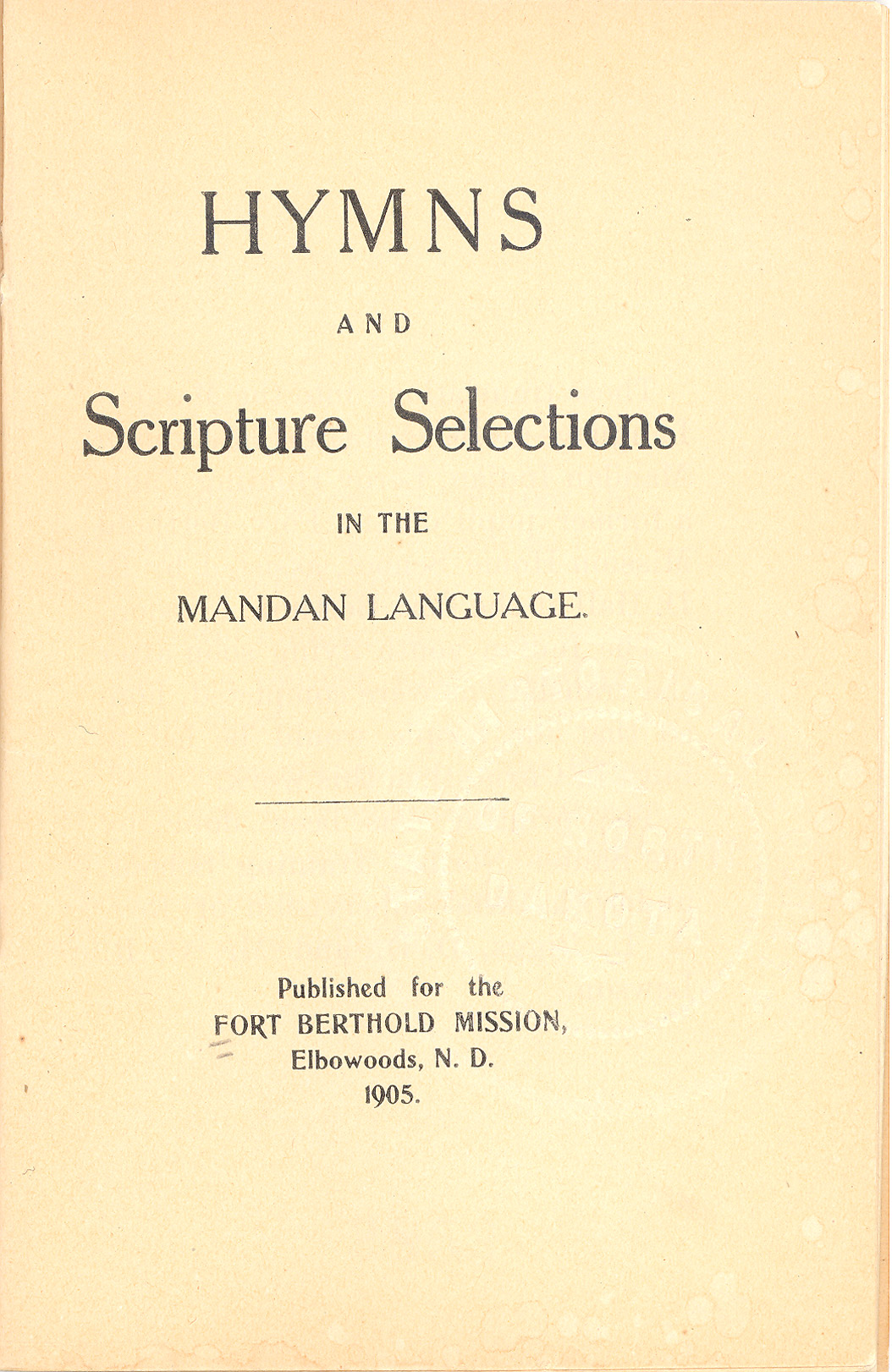

At Sunday services at the mission church, the congregation sang popular hymns in Hidatsa or Mandan (Arikara translations came later.) (See Document 6) Because the English-speaking employees of the reservation agency attended services, Reverend Hall also spoke in English throughout the service.

Why is this important?Anglo-Americans assumed that Christianity was the foundation of civilization. If Indians accepted Christianity, then they were prepared to take on the other characteristics of civilization such as education and private ownership of property. Reverend Hall and other missionaries were sincere in their religious beliefs and wanted Indians to share in their faith. However, missionaries also believed that faith was empty without significant cultural change. Reverend Hall and other missionaries worked closely with the federal agents on reservations to force cultural change on the reservations.

While some Christian missionaries believed that American Indians could become fully individualized citizens, others believed that Indians would always be subordinate to white Americans. One commenter, Dr. J. J. Best, noted that mission schools taught Indian children “as in the free schools throughout Virginia” which were established to educate African American children. Best expected that Indian children would be trained to work at mechanical or farming jobs. They would also study reading, writing, and arithmetic. And the students would also learn how to acknowledge the superiority of whites. This is evident in the Fort Berthold Mission School document, rule number 23. Male students were to touch their cap when meeting an officer of the school. In the nineteenth century, a man touched his cap to another man who was supposed to be his superior. It was a habit that African American men were expected to adopt. At Fort Berthold mission school, young boys were also taught to defer to white men.