During the summer of 1875, there were two events of great importance to the Lakotas. In mid-summer, the Hunkpapas, under the leadership of Sitting Bull, strengthened their alliance with the northern Cheyenne tribe. The two tribes met on Rosebud Creek in southeastern Montana Territory. The Lakotas and Cheyennes participated in a Sun Dance ceremony that joined the two tribes in a pledge to face their enemies together. At the time, they did not know that their greatest enemy soon would be the U. S. Army. (See Document 1)

Shortly after the Sun Dance, the Hunkpapas were invited to attend a council with federal representatives at the Red Cloud agency in western Nebraska. The council was called to discuss the sale of the Black Hills to the U. S. government. Sitting Bull and many others refused to go to the council. For Sitting Bull, the Black Hills were not only sacred, but were a place where food could always be found. The council failed to reach an agreement.

The government representatives returned to Washington believing that the Sioux would never give up their legal right to the Black Hills until they “felt the power of the United States.” On November 3, 1875, President Grant, some generals, and officials of Indian Affairs Commission met at the White House. These men made two decisions. First, the Army would not interfere with miners prospecting for gold in the Black Hills. Second, the government prepared to use the Army to force non-reservation Sioux to give up some of their hunting lands and settle on the Great Sioux Reservation. Government officials said that the Sioux had violated the Treaty of 1868. However, the Sioux who did not live on the reservation had not signed the Treaty of 1868.

The government decided on a winter campaign against the non-reservation Sioux. On December 6, 1875, reservation agents received an order to send runners to the winter camps ordering the Sioux to the reservation by January 31, 1876. If they did not come to the reservation, the Army would march to their camps.

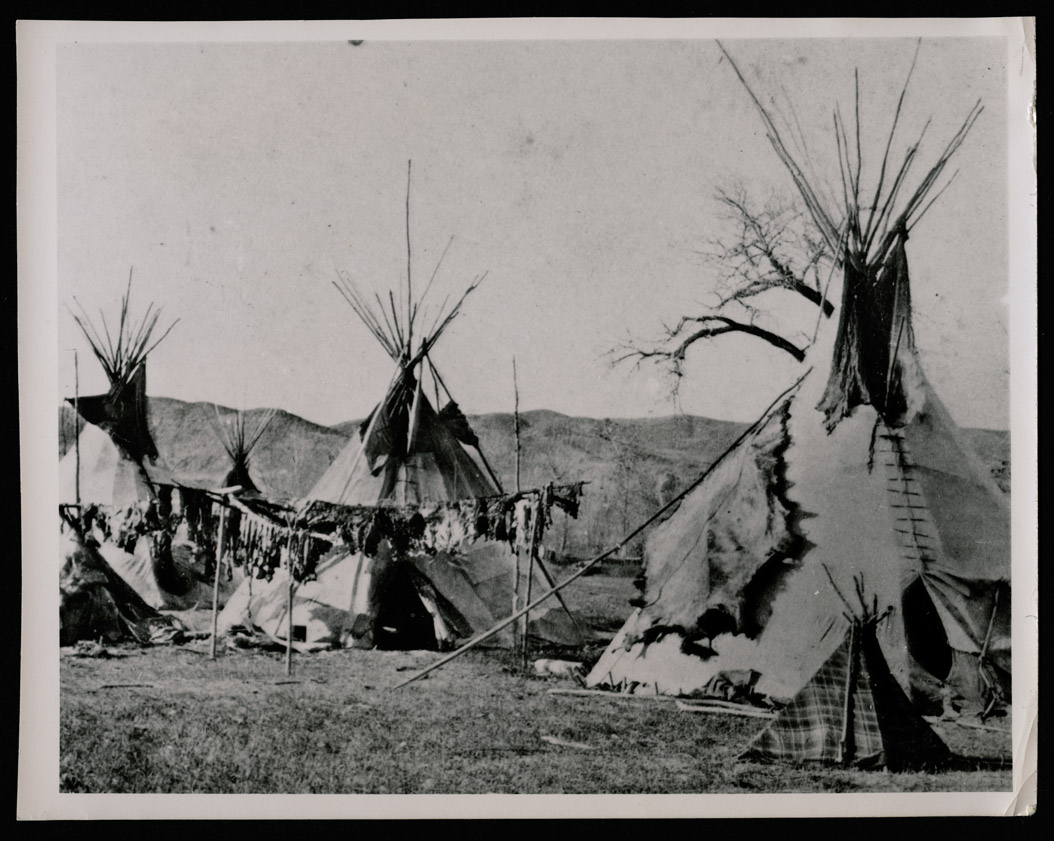

The Hunkpapas were in camp on the Yellowstone River near the mouth of the Powder River in southeastern Montana. Other tribes were a little farther west on the Tongue River. For the most part, the Sioux in these camps were planning raids on their old enemies the Crows and Arikaras, but had no plans to go to war with the U. S. Army. They considered the orders to move to the reservation an invitation which they were unable to accept. Reports from the winter camps give us two views of Sitting Bull. He continued to tell visitors that he would die before he would give up his life of freedom in the tradition of his father. He also stated that he was at peace and had no quarrel with the U. S. Army as long as the Army did not bother him.

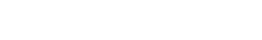

The peace of the winter camps was broken on March 17, 1876 when soldiers attacked a remote Cheyenne village on the Powder River. (See Image 6) General George Crook organized the attack, mistakenly thinking that his troops were attacking the winter camp of Crazy Horse. The soldiers burned much of the village and killed two men before the Cheyennes drove the soldiers away. The remaining Cheyennes made their way to Sitting Bull’s village where they were warmly welcomed and given food and shelter.

After the Cheyennes arrived at the Hunkpapa village with news of their battle, Sitting Bull and the other chiefs began to prepare for more battles with the Army.

The soldiers were also preparing for war, but a winter campaign was impossible. It was an extremely cold and snowy winter. The army needed support from steamboats, but the boats could not move until the river ice broke up in May. In the meantime, the Army and the Sioux began to plan for a major battle.

Why is this important? For decades, both the United States government and American Indians had faced the problem about which culture, or which people, would control the Great Plains. Treaties did not solve the problem. Reservations provided an acceptable answer to the government, but for many Lakotas reservation life was not acceptable. It is not surprising that officials in Washington, D.C. were frustrated and angry with the Lakotas. It is not surprising that the Lakotas wanted to continue to live as they always had and did not trust the federal government.

Was the coming conflict avoidable? This is a question that historians debate quite often. Was there another solution to the conflict between two very different cultures that viewed the land differently, had different systems of governance, and prayed differently? It is probable that some sort of solution might have met the needs and interests of both sides. However, between January and June of 1876, both sides stood firm on their own decisions and ceased to communicate about solutions. At that point, armed conflict became inevitable.

Document 1

By the fall of 1875, it was clear to Army leadership that only strong military force would bring Sitting Bull’s Hunkpapas (a band of the Sioux nation) and other non-reservation bands to The Great Sioux Reservation. During 1875, Sitting Bull did not share that view. He worked to establish an alliance with the Cheyenne, but considered his relationship with the Army to be peaceful unless the Army attacked.

The Hunkpapas continued to live as they always had. They hunted and camped along the tributaries of the Missouri and Yellowstone Rivers. They raided Arikara, Mandan, and Hidatsa villages for horses. They laid siege to Fort Pease, a fur trade post on the Missouri River and occasionally attacked remote settlements or wagon trains. The Hunkpapas made it clear that whites were not welcome in their traditional lands, but usually did not attack unless they were provoked.

As we read reports and letters written by Army officers and federal reservation agents, we can see their increasing fear that Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse, and other Lakotas were becoming a greater danger to Indians of other tribes, white settlers, and the Army. There are, however, few specific facts cited to back up the statements. By the end of January, 1876, the Army leadership decided to organize a military campaign against Sitting Bull and the Lakotas.

The following excerpts have been selected from official transcripts of military communications between November, 1875 and March, 1876. The letters reveal the preparation for the battles that finally occurred in June, 1876. In the excerpts, ellipses (. . . ) indicate where words have been removed to shorten the entry. Editor’s additions to the text are enclosed within brackets [XXX]. Copies of the full text of the letters are attached. You can read more of these officers’ letters at: House Documents, Otherwise Publ. as Executive Documents: 13th Congress, 2d Session-49th Congress, 1st Session (Google e-Book)

March 10, 1871. Captain W. Clifford to Commissioner of Indian Affairs Ely S. Parker.

“. . . Not long since these Sioux attacked a train between F[or]ts Buford and Peck, killed one man, wounded another, and captured the whole train. Afterward they told the Arrickarees that, that was but the beginning of what they meant to do. They say that they have waited two years for the Govt. [government.] To fulfill its promises, and will wait no longer, that all white men are liars, and as soon as the grass is green they will show the Govt. they can still fight. They say that they know they will be whipped, but that they prefer to die fighting than starve as they must do now that there are no more buffalo.”

November 9, 1875. E. C. Watkins, Inspector U. S. Commission on Indian Affairs to E. P. Smith, Commissioner of Indian Affairs.

“. . . Sitting Bull’s band and other bands of the Sioux Nation, . . . roam over Western Dakota and Eastern Montana, including the rich valleys of the Yellowstone and Powder Rivers, and make war on the Arickarees, Mandans, Gros Ventres [Hidatsas], Assinaboines, Blackfeet, Piegans, Crows, and other friendly tribes. . . .

Their country is probably the best hunting–ground in the United States, a “paradise” for Indians, affording game in such variety and abundance that the need of Government supplies is not felt. . . . They. . . boast that the United States authorities are not strong enough to conquer them. The United States troops are held in contempt, and surrounded by their native mountains, relying on their knowledge of the country and powers of endurance, they laugh at the futile efforts that have thus far been made to subjugate them, and scorn the idea of white civilization.

They are lofty and independent in their attitude and language to Government officials, as well as the whites generally, and claim to be the sovereign rulers of the land. They say they own the wood, the water, the ground, and the air, and that white men live in or pass through their country but by their sufferance.

They are rich in horses and robes, and are thoroughly armed. Nearly every warrior carries a breech-loading gun, a pistol, a bow and quiver of arrows. . . . And yet these Indians number, all told, but a few hundred warriors, and these are never all together or under the control of one chief. In my judgment, one thousand men, under the command of an experienced officer, sent into their country in the winter, when the Indians are nearly always in camp, and at which season of the year they are the most helpless, would be amply sufficient for their capture or punishment.

The Government has done everything that can be done peacefully to get control of these Indians . . . . They are still as wild and untamable, as uncivilized and savage, as when Lewis and Clarke first passed through their country.

The injurious effects of the repeated attacks made by these bands on the peaceful friendly tribes . . . cannot be overestimated. . . . No Indians can be expected to “civilize,” to learn to cultivate the soil . . . if while they have the implement of labor in one hand they must carry the gun in the other for self-defense. . . .

The true policy, in my judgment, is to send troops against them in the winter, the sooner the better, and whip them into subjection. . . .

The Government owes it, too, to these friendly tribes. . . . to the agents, . . . . to the frontier settlers . . . . It owes it to civilization and the common cause of humanity.”

November 21, 1875. Daniel Huston, Jr., to Department of Dakota. “Sitting Bull . . . intended to annoy . . . Forts A. Lincoln and Buford, all he could this winter, by burning hay stacks and out buildings and killing any one found outside of the forts.”

The federal agency that held authority over Indians on reservations was the Commission on Indian Affairs. The Commission and the Army were often at odds over Indian policy and control of the reservations. While the Commissioner and the generals in Washington, D. C. were trying to find a solution to Sitting Bull’s resistance, the local federal Indian agent was quarreling with the local Army officer about distributing ammunition to the residents of Standing Rock and about which agency held authority at Standing Rock.

January 31, 1876. J. Q. Smith, Commissioner of Indian Affairs to Agent Burke at Standing Rock.

“Cannot recommend extension of Sitting Bull’s time to come in. He probably received full notice. Matter is now left to War Department.”

Throughout January 1876, many letters were sent to Washington, D.C. military offices and to the Army’s Department of Dakota headquarters in St. Paul, Minnesota. The letters concerned the movements and activities of the Sioux. The Sioux were said to be at Turtle Mountain, which turned out to be Turtle Mountain in western Montana, not North Dakota. Rumors said that the Sioux had attacked the horses of the Hidatsas (Gros Ventres) and that the Hidatsas had killed and scalped four Lakotas. That rumor was false. Agents and officers speculated about how many and how modern the Lakotas’ guns were. These letters indicate that the Army is striving to gain accurate and useful information for its planned campaign. Gossip and misinformation filled every letter, but some letters began to raise serious concerns for the Army.

In March, 1876, Major John Brisbin marched his troops from Fort Ellis in western Montana east to the Yellowstone River seeking to find out about the location or movements of Sitting Bull’s band. After a winter journey of nearly 400 miles, he had nothing to report.

However, on March 17th, troops under the leadership of General Reynolds attacked the village where Crazy Horse’s Oglala Lakotas along with some Cheyennes and Minneconjou Lakotas were camped. Reynolds and his superior officer General George Crook were satisfied that they had found a connection between the non-reservation Lakotas and those who lived at Red Cloud and Spotted Tail agencies.

March 25, 1876. Whipple, Assistant Adjutant General (writing for General Crook) to General W. T. Sherman.

“General Reynolds, with part of command, was pushed forward on a trail leading to village of Crazy Horse, near mouth of Little Powder River. This he attacked and destroyed on the morning of the 17th, finding it a perfect magazine of ammunition, war material, and general supplies. Crazy Horse had with him the Northern Cheyennes, and some of the Minneconjoux, probably in all one half of the Indians of the reservation. . . . Had terrible severe weather during absence from wagon-train; snowed every day but one, and the mercurial thermometer on several occasions failed to register [because the temperature was so low].”