On February 2, 1915, the North Dakota chapter of the American Society of Equity held its state convention in Bismarck. Even though farm crops and wheat prices had been pretty good for a few years, farmers were still waiting for the state to take action on a terminal elevator. Some members believed the time was right for political action.

Governor L. B. Hanna had campaigned for his second term in 1914 with a promise of a North Dakota-owned elevator in Minnesota. Many farmers distrusted Hanna on this issue because the Republican Party had never before supported a state elevator. The legislature had received a 600-page report stating that the state should not build a terminal elevator.

A new idea began to surface at the Society of Equity state meeting. The idea was to create a nonpartisan political organization of farmers. During the Equity convention, Treadwell Twichell, a Republican legislator from Cass County, met with Equity members. Twichell told the farmers that they should leave government to the legislature and that they should “go home and slop the hogs.” It is possible that Twichell never said those words—he denied saying them—but the members of Equity believed that he had, and it made them very angry. The idea of a new, politically oriented farmers’ organization was very appealing to these angry men.

The man who came up with the new idea was probably Albert Bowen. He and Arthur C. Townley had been organizers for theSocialist Party.The Socialist Party reached its peak of popularity in the United States between 1910 and 1920. The Socialist Party stood for economic reform with a special interest in state ownership of factories and other businesses. Many members of the Socialist Party were unskilled laborers who lived in large cities.

The Socialist Party based its philosophy on socialism. Socialism was an idea (or theory) that capitalism (an idea or theory based on private ownership of land and production) failed to distribute products and wealth equally. Socialism called for government ownership of “the means of production” such as factories which would prevent wealth from accumulating in the hands of only a few people.

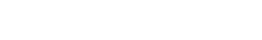

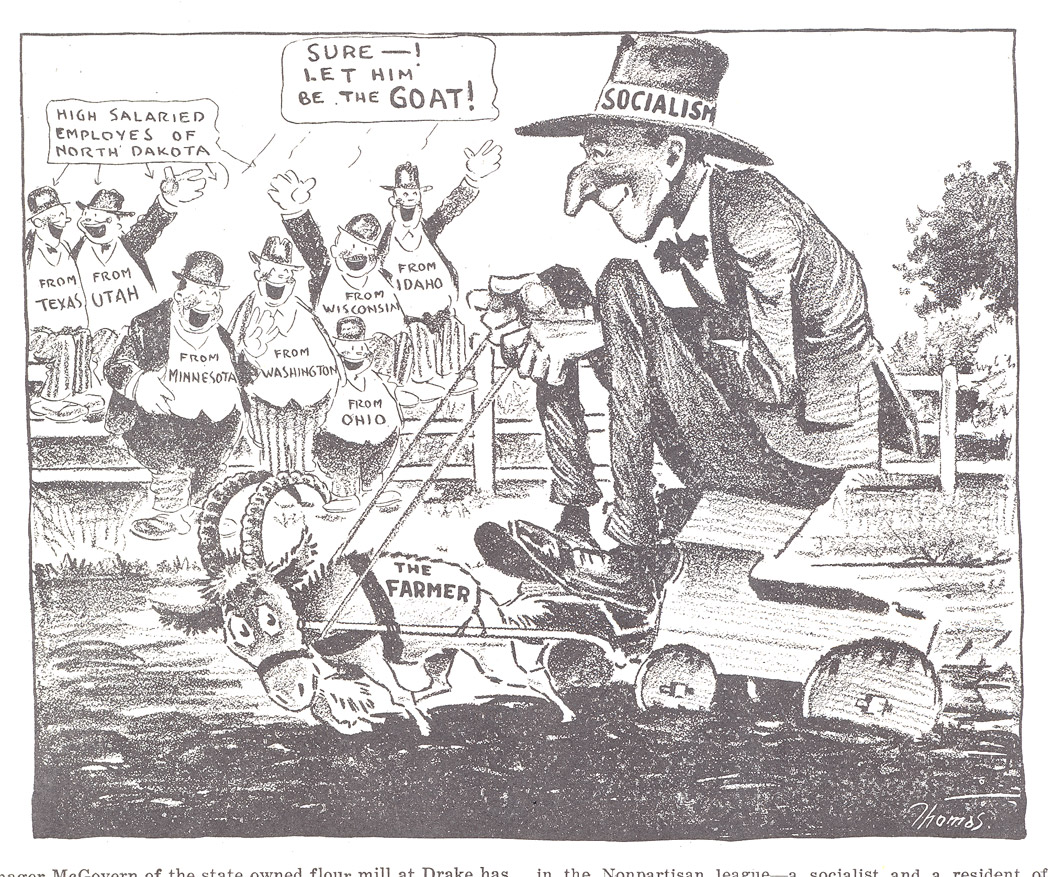

In North Dakota where there were few factories, socialists wanted the government to own and operate grain elevators, flour mills, and railroads. Since most socialists in North Dakota in 1915 were farmers, they wanted to retain ownership of their own land. North Dakota socialists and Leaguers were actually capitalists who believed in the regulation of corporate capitalism. Bowen and Townley resigned from the Socialist Party to organize the Nonpartisan League (NPL). Soon, Townley was driving around North Dakota in a Ford Model T meeting with farmers to encourage them to join the NPL. (See Image 1) The membership fee was $6 ($134 today), a lot of money for farmers in those days. The fee included a subscription to the NPL newspaper, The Leader, which began publication in September, 1915. (See Document 1)

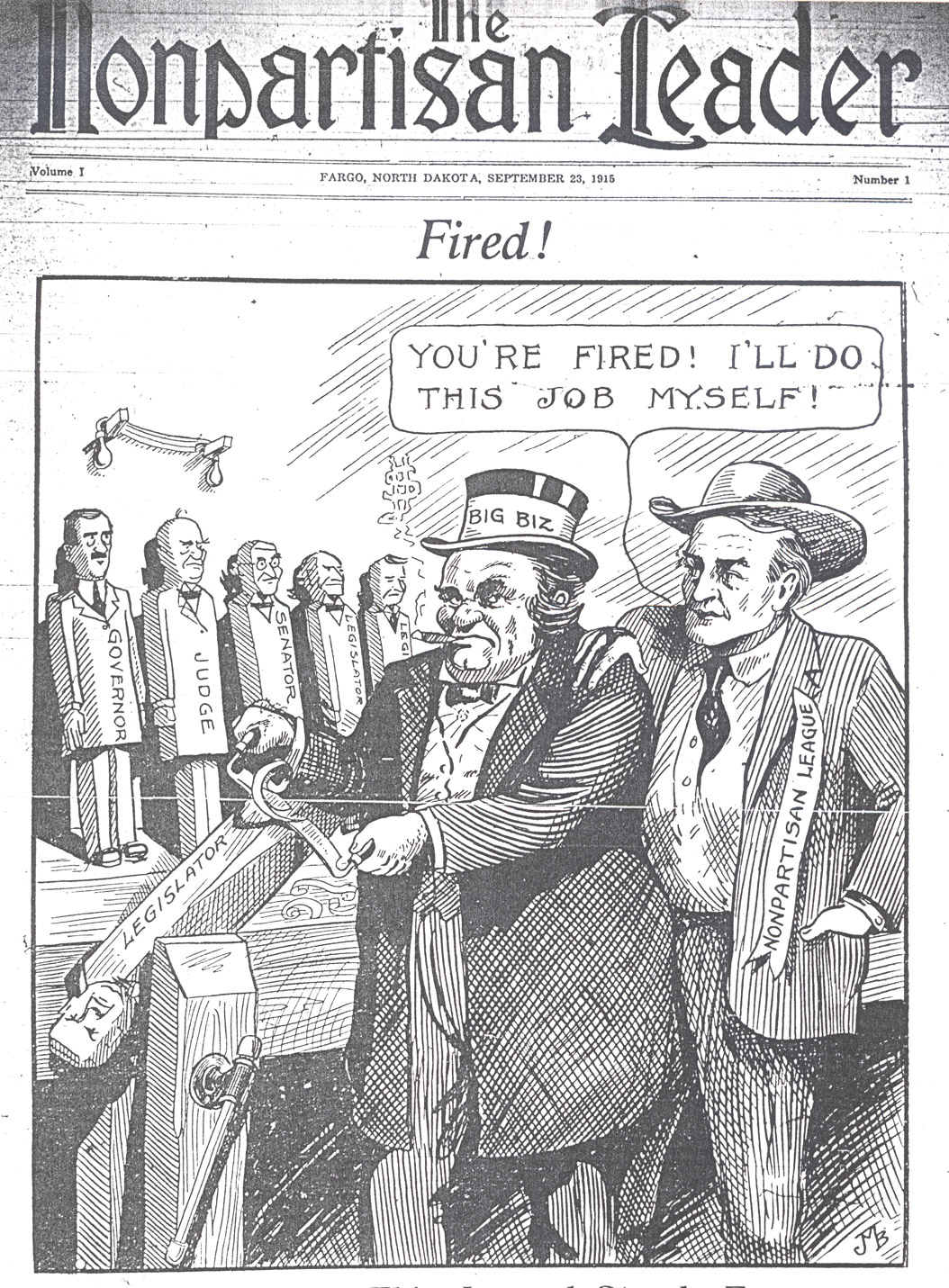

A few NPL leaders put together a set of principles the organization supported. Many of these principles were similar to the principles of socialism. The platformA platform is a statement of the basic ideas of a political party. Each platform principle is called a plank in the platform. Some planks are vague or theoretical, but other planks promise action. The planks of the Nonpartisan League promised action on a state-owned terminal elevator and other issues important to farmers. included: state owned terminal elevator and flour mill, state owned cattle slaughtering plants, state inspection of grain, state hail insurance, and low interest loans from rural-credit banks. (See Document 2)

In 1916, the NPL held a convention and nominated several candidates for office and legislative seats. Their plan was to have their candidates endorsed by either the Republican or the Democratic Party. The League was rapidly growing in membership (40,000 members by 1916) and had state-wide support, though it continued to be most popular among farmers. (See Image 2) Critics reminded voters that the NPL had socialists among its members and that its platform had many socialist characteristics. Critics said that “State [owned] farms will follow state flour mills.”

The 1916 elections resulted in several victories for the NPL. Lynn Frazier, a farmer from Hoople, won the governor’s seat. William Langer was elected Attorney General, Thomas Hall was re-elected Secretary of State, and Carl Kositzky was elected state auditor. All were NPL nominees and very capable men. The League won a majority of seats in the state House of Representatives, though it lacked a majority in the Senate. North Dakota was ready to proceed with its political experiment.

Why is this important? The NPL rose at a time when socialism had some power in the United States, but socialism was mostly an urban movement. In North Dakota, new ideas, some drawn from socialism, were applied to the problems farmers faced. The NPL found a great deal of support and brought good people into the organization. The NPL spread to other states, too, particularly Minnesota.

The Nonpartisan League finally gave North Dakota farmers the political power and political positions they had been seeking since organizing the Farmers’ Alliance in 1886. The Farmers’ Alliance and American Society of Equity had also asked for state-owned grain elevators and state regulation of railroads and grain-grading. With the NPL holding many seats of government, it appeared that farmers would finally have a powerful voice in government.

The Nonpartisan League changed state politics between 1915 and 1922. The changes were both good and bad for North Dakota. Some of the League’s ideas worked well and are still part of North Dakota’s modern economy.

Arthur C. Townley

At the end of his life in 1959, Arthur C. Townley could claim to have once been at the pinnacle of political success in North Dakota and much of the nation. He had also reached the depths of poverty and infamy. He was an enormously capable leader and promoter, but often lost track of the personal and social values that made his goals worthy.

Townley was born into a large family in Brown’s Valley, Minnesota in 1880. His parents were poor, but Townley graduated high school and began teaching in country schools. He soon moved to western North Dakota where he settled on a homestead near Beach. He left his homestead after a few years and went to Colorado. In Colorado, he worked as a promoter for a bonanza wheat farm which ultimately failed. He returned to North Dakota with his new wife and step-daughter. He developed a 7,000 acre bonanza flax farm near Beach. He failed to make this farm pay, and he owed money to many creditors. Townley was discouraged by the difficulty of making a living in farming.

Townley then joined the Socialist Party as an organizer. He was a good organizer, traveling from farm to farm to meet personally with farmers and sign them up for membership. Around 1915, the party grew suspicious of his methods and his leadership skills and forced him out. His departure from the Socialist Party coincided with the rise of the Nonpartisan League (NPL). Townley became an early organizer and leader of the new farmers’ organization.

In his work for the NPL, Townley met with great success. He bought Model T Fords for himself and other organizers so they could travel all over the state signing up new members. Townley also traveled nationally, creating NPL organizations in 20 western states and a national Nonpartisan League headquartered in Minneapolis, Minnesota. (See Image 3)

The NPL had its greatest strength in North Dakota while the United States was engaged in war against Germany (World War I.) Townley, like many other socialists, wanted the United States to stay out of the war and discouraged young men from joining the Army. For this, he was arrested and convicted in Minnesota in 1919. After serving a 90-day sentence, he returned to North Dakota to find that he was no longer welcome in the NPL. Many of his former friends wanted to keep their distance from him.

The NPL had begun to lose its standing in North Dakota and elsewhere. Townley looked around for other work. Using his ideas, experiences, and network of friends, he formed another farmers’ organization called the National Producers Alliance. His plan with this organization was to stabilize farm prices through cooperative sales of crops. The remaining members of the NPL attacked the organization and attacked Townley personally as a friend of communism. Once again, he was forced to give up the program.

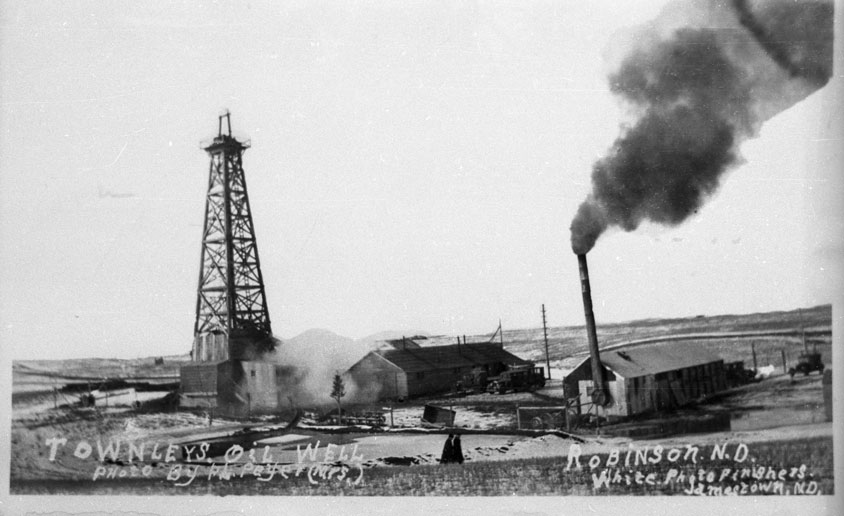

After his departure from the Nonpartisan League, Townley was involved in a number of schemes. Some schemes were clearly fraudulent. One of his schemes was oil development. He borrowed $250 from “investors,” many of them old NPL friends. Townley drilled wells near Robinson and in several other locations. The wells did not produce and his friends did not get their money back. (See Image 4)

In 1930, Townley planned to run for Congress. His campaign featured his belief that prohibition (now law in the United States) should be repealed, so that the government could own and operate breweries and distilleries.

Townley eventually denounced socialism and became a follower of the infamous Senator Joseph McCarthy who falsely claimed that communists worked for the federal government. In the 1950s, Townley came to believe that North Dakota’s state-owned bank and mill could not be operated as efficiently as privately owned businesses.

As Townley’s life spiraled downward, his schemes became stranger. He became a faith-healer for a while. When oil was discovered in western North Dakota in 1951, Townley tried to sell “doodle-bug” services to petroleum engineers. Townley said that a doodle-bug could find oil underground by means of a dousing, or witching, rod that would tip downward when passed over the oil pool. Townley died in a car accident near Minot in 1959.

Why is this important? Arthur C. Townley was a man of dreams. He was an extraordinary leader who could convince an individual or a crowd to follow him. Townley was able to funnel the farmers’ interests and untapped political power through his hands into the Nonpartisan League. Without Townley’s leadership, it is unlikely that the League would have achieved state-wide political power. However, Townley probably did not have the intellectual ability or political sophistication necessary to support his role in the expansion of the League. The nature of Townley’s dictatorial control over the NPL and state government undermined the most important idea of the League that farmers could serve as elected officials and meet their economic needs through democratic political processes.

The Goat, A Symbol of the NPL

“I’ve got your goat” is a phrase that means that someone has irritated another person. Often the source of that irritation is a truthful idea that someone doesn’t want to recognize. The phrase was commonly used in the early 20th century.

The Nonpartisan League (NPL) adopted the goat as its symbol. Goats appeared at NPL and American Society of Equity (a farmers’ organization) meetings. At some meetings, whenever a speaker mentioned Governor L. B. Hanna, someone would bring in a goat wearing a banner that read “The Rubes Have Hanna’s Goat.” Rube was a term that often referred to a rural, uneducated person. North Dakota farmers thought that government officials who paid them little attention demeaned farmers by calling them rubes.

In 1916, when Governor Hanna was running for re-election against the NPL-sponsored candidate Lynn Frazier, two children came to an NPL picnic with a goat wearing a sign that said “We have got Hanna’s goat.” (See Image 5) The goat appeared on the speaker’s platform and the NPL crowd had fun watching the goat in his special outfit.

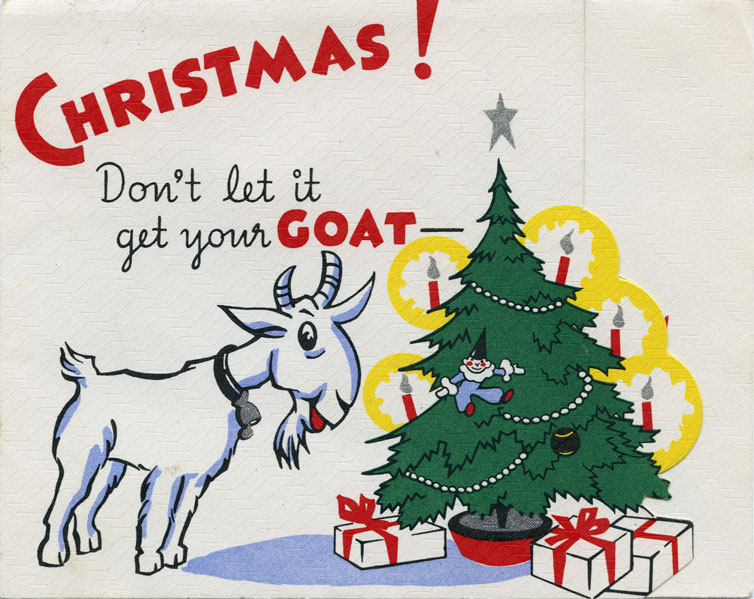

By 1918, NPL members were singing songs at their meetings. One popular song used the phrase “The league now will make the Boss the ‘goat.’” The goat became the official symbol of the NPL in October 1919. The organization stated that “in order to enter a decided kick against the manifest wrong done them and the great cause that we do hereby adopt as our permanent emblem – THE GOAT that can’t be got.” Members wore goat pins and the goat appeared in photographs and even Christmas cards. A person displaying the goat symbol was declaring his or her affiliation with the Nonpartisan League. (See Image 6)

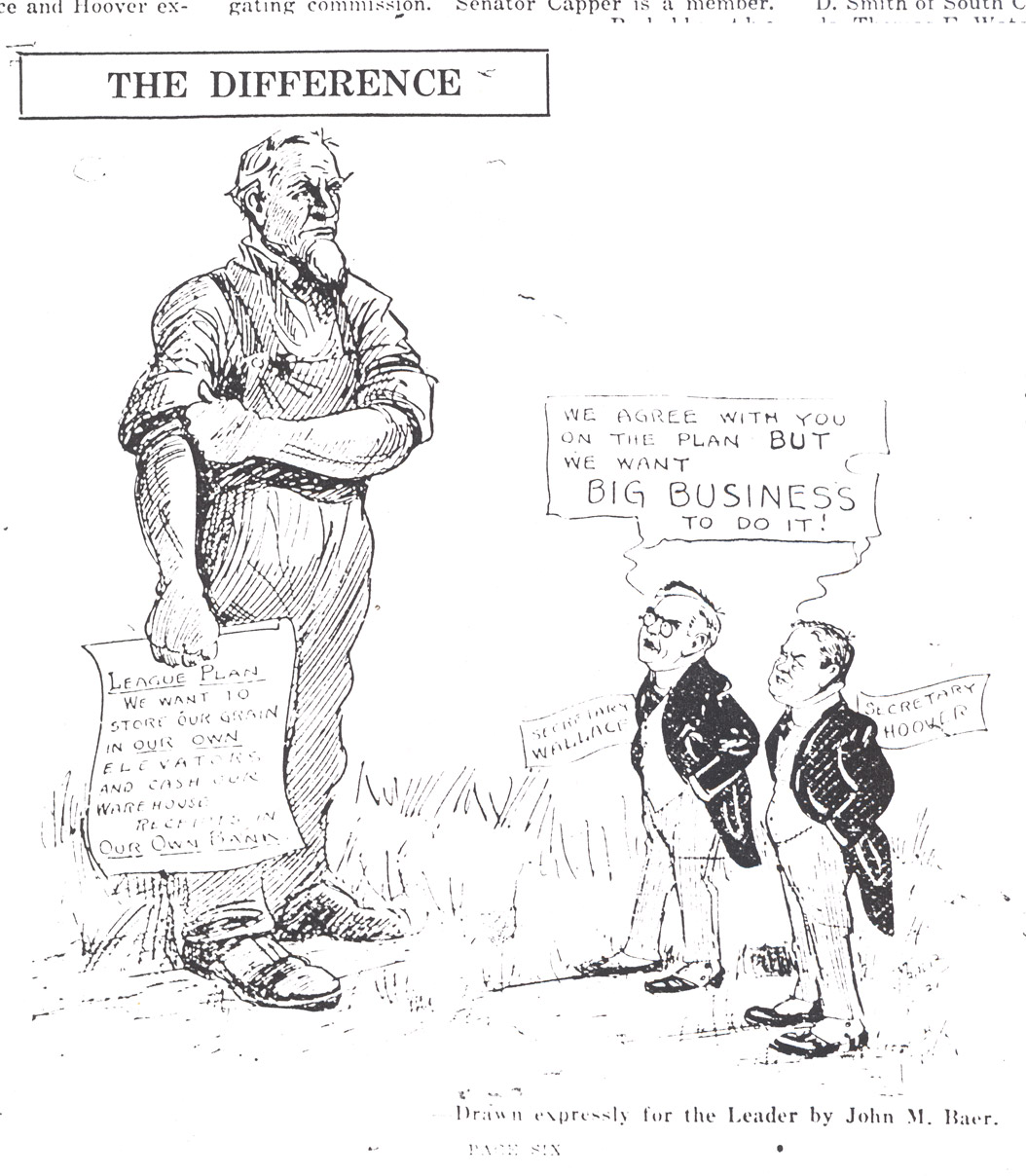

The NPL goat was open to all kinds of uses for NPL cartoonists and speakers. The goat could “butt” its opponents, it could “kick” against wrong-doing. Governor Lynn Frazier said that goat was an animal “that works with its head when attacked.” (See Document 3)

The goat was a very popular symbol. In Montana, NPL members put on a play titled The Donkey the Elephant and the Goat.” In the play, the three political party symbols (Democratic Party, Republican Party, and the NPL) debate issues and attitudes. The goat, of course, is the smartest and nicest of the three symbols. The goat states:

If I’m beyond your courtesy,

I still have vocal powers,

So lend those mighty ears to me

For half a dozen hours

I know that I am but a goat

All battered by the weather,

But in this land I have a vote,

And I won’t sell it, nether!

. . . .

The workers that I represent

Are not of one vocation,

But every one who earns a cent

Has there an invitation.

The goat shared space in NPL cartoons with Hi’am A. Rube whose name is later shortened to Hiram Rube. Hi is an Uncle Sam-like character. He is tall and lean and has a pointed beard. He wears overalls and a straw hat. Hiram Rube represented honesty and morality in politics. (See Document 4)

Why is this important? Political symbols help people identify their political positions. Political cartoonists used many different kinds of symbols to add deeper meaning to their cartoons without adding a lot of words. A symbol has meaning without words.

North Dakota farmers liked the goat symbol. The goat was humble, but proud. The goat was nimble, funny, and smart. North Dakota NPL members identified with the way a small animal could defeat larger opponents with its head.

Sources: Lansing, Mike. Insurgent Democracy: The Nonpartisan League in the North American West. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014.

The full script of “The Donkey, The Elephant and The Goat” can be found online: http://archive.org/details/donkeyelephantgo00pres