Television Introduction

The history of television is much longer than we might think. Experiments in transmitting images began in the 19th century. By 1928, Charles Jenkins was broadcasting “radiovision” from station W3XK near Washington, D.C. He sold receivers (television sets) to a few thousand people who believed in the future of television. To support the costs of transmission, Jenkins sold commercial time until the federal government fined him and told him not to do it again.

Around the same time, station WRGB began broadcasting independently from Albany, New York. None of the earliest stations were part of a national network system. Programs were broadcast by local stations for only a few hours a day. Historians estimate that in 1936, only about 200 commercially available televisions were being used around the world.

On January 12, 1940, the National Broadcasting Company (NBC) initiated the first network programming. The uninspiring play, “Meet the Wife,” was broadcast from the NBC station in New York to a station in Schenectady, New York.

Early television stations such as NBC grew out of radio broadcasting stations. The stations were closely affiliated with companies that manufactured and sold radio (and later television) equipment. The Radio Corporation of America (RCA) purchased a radio station in 1926 and created the National Broadcasting Company (NBC) with its partner General Electric (GE). General Electric sold its shares in 1930, but in 1986, GE purchased RCA and NBC.

As radio programs and personalities such as Jack Benny, Bob Hope, and Abbott and Costello, made the transition from radio to television, the government recovered from its refusal to allow stations and networks to sell commercial time. Advertising on TV became closely associated with specific programs and stars. The Texaco Star Theatre starred comedian Milton Berle, known to most Americans as “Mr. Television.”

NBC and other television networks introduced television to a wider public at the 1939 Worlds’ Fair in New York. President Franklin Roosevelt visited the Fair, and on April 30, 1939, became the first U.S. President to appear on television.

Television development slowed during World War II, but after the war, commercial stations began to “sign on” around the United States. Broadcasts lasted a few hours a day and consisted of news, sports, dramas, comedies, and musical performances.

Color television was available in the 1930s, but few families owned a color television set. Most programming arrived in black and white images. Each television company tried to create its own color technology. However, when it became apparent that CBS’ color technology was not compatible with RCA televisions which were developed for NBC programming, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) denied CBS a license to broadcast in color. Though this was a setback for color broadcasting, the loss was small. There were only 6,000 television sets in the U.S., and most were in New York City.

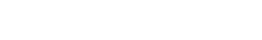

But television was gaining ground. The numbers of home televisions multiplied quickly. By 1949, there were 3 million sets, and 12 million in 1951. However, the growth of the industry depended on the development of local stations (or affiliates) of the national network television companies. Local television stations did not appear in many western states until the mid-1950s. (See Map 2.)

Though television was a new and relatively expensive communications system, people were excited about television. It provided information in the form of news and weather forecasts that helped people plan their work and leisure. People enjoyed relaxing with sports and entertainment programming. Families gathered around the television set to watch programs together. Through the medium of television, North Dakotans were directly connected to the political and business centers of New York and Washington, D.C. The world grew smaller and more familiar as people tuned in to network television.

Television in North Dakota

By 1951, several radio stations in North Dakota were planning for new operations in television. Rural states like North Dakota faced several problems in acquiring television. The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) had to issue a license. Requests for television broadcast licenses increased dramatically after World War II (1941-1945) and the FCC decided to issue licenses according to the population of the broadcast area. Not surprisingly, North Dakota cities were not highly ranked. Fargo, our largest city, was 114 on the list.

Nevertheless, broadcasters prepared. They hired staff for behind-the-scenes production and “on air.” Some people had a part in both. Ken Kennedy, program director for WDAY in Fargo was also known on air as a comic character, Ole Anderson. Harry Jennings was staff photographer and part-time musician. Jennings’ young son, Wayne, acted in commercials. The stations had many bills to pay before they could “sign on,” so every employee was mined for talent.

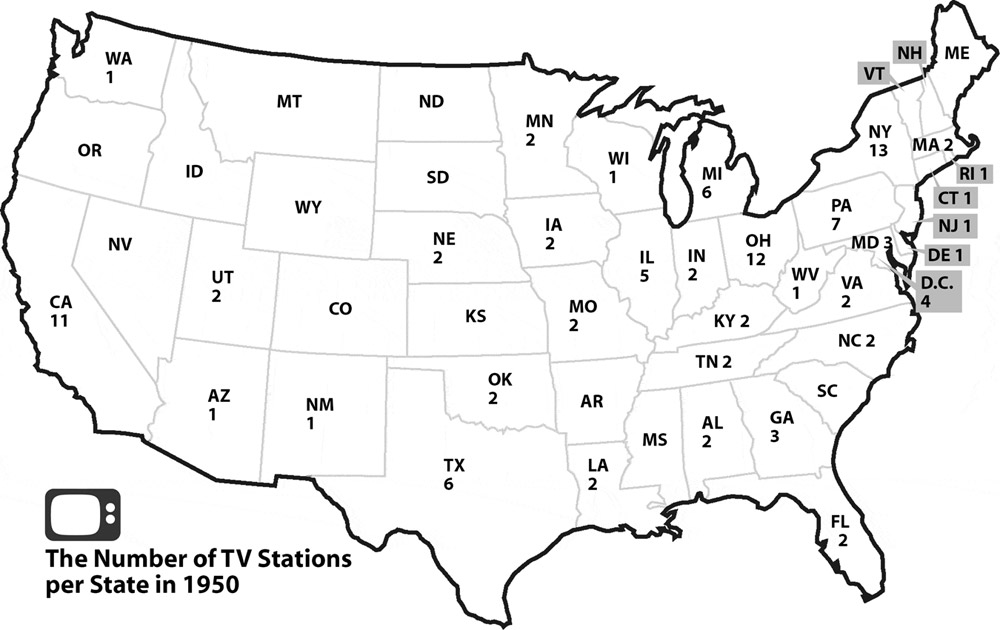

Three stations went on air in 1953. KCJB-TV in Minot was first on April 4, 1953. Then, WDAY-TV in Fargo on June 1, 1953, and KFYR-TV in Bismarck on December 19, 1953. (See Document 6) The Minot station hoped to reach viewers beyond a 30 mile radius and asked viewers to send in a postcard telling of their television reception. The postcards gave the stations an idea of how many viewers they had which was helpful in selling advertising.

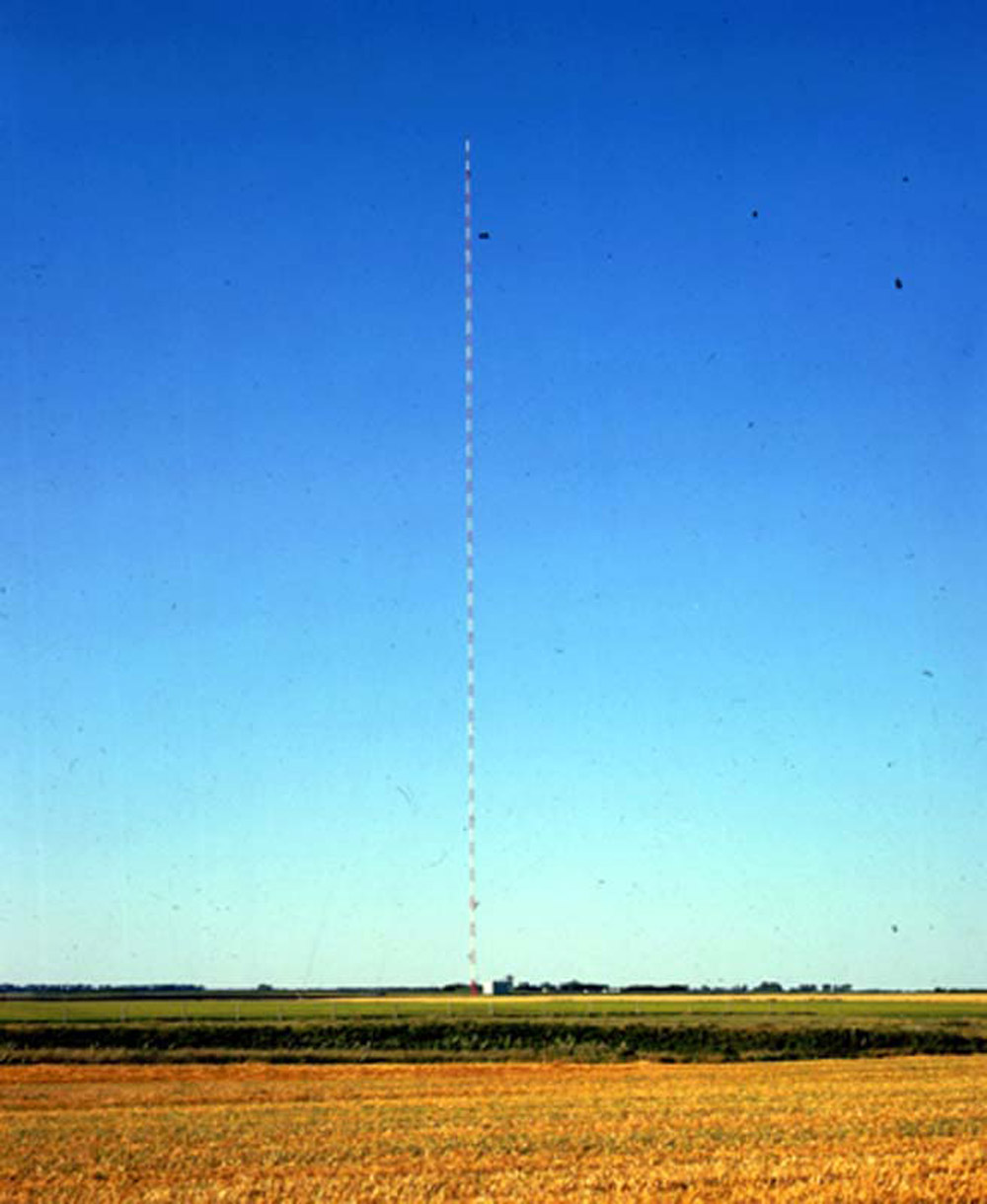

Few people, especially outside of larger towns, had televisions. (See Image 17.) Television sets were relatively expensive; an RCA TV set in 1954 ran around $190 ($1,600 today). Many people thought there was no point in having a TV set before there were broadcast stations in the area. However, some eastern North Dakota families bought TVs and set up their own reception towersLocal television was broadcast from a tower that was connected directly to the transmission studio. The signal from the tower might serve an area 30 to 50 miles away. In 1963, the Fargo station, KTHI-TV, built a transmission tower (or mast) three miles west of Blanchard that was the tallest structure in the world for many decades. It stood 2,063 feet above the ground. The tower broadcast TV signals to homes within a radius of 55 miles.

Each TV set had to have an antenna to receive the signal. If the antenna was on the TV set, it was usually an arrangement of two heavy-gauge wires commonly called 'rabbit ears.' Some houses had an antenna on the rooftop with a wire leading into the house that was connected to the television set. Weather, radio waves, and other sources of electrical interference broke up the reception causing the TV screen to be filled with tiny, flickering, white dots called 'snow.' Reception might be improved by fine adjustment of the channel or tuning knob. Many owners believed that a good 'whack' on the side of the TV cabinet would fix everything. to pick up broadcasts from Minneapolis. Some appliance stores sold TVs before the stations began broadcasting. (See Image 18.) If people wanted to know more about TV before they purchased one, they could go to a bar to watch or stand in front of an appliance store window during a broadcast.

In the beginning, North Dakota TV stations broadcast an hour or more of local programming daily. News and weather were important, but they also had local entertainers who performed in a small studio. A single large microphone picked up the sound. One or two cameras televised live programming. Entertainment ranged from comedy to orchestra to western music. (See Image 19.)

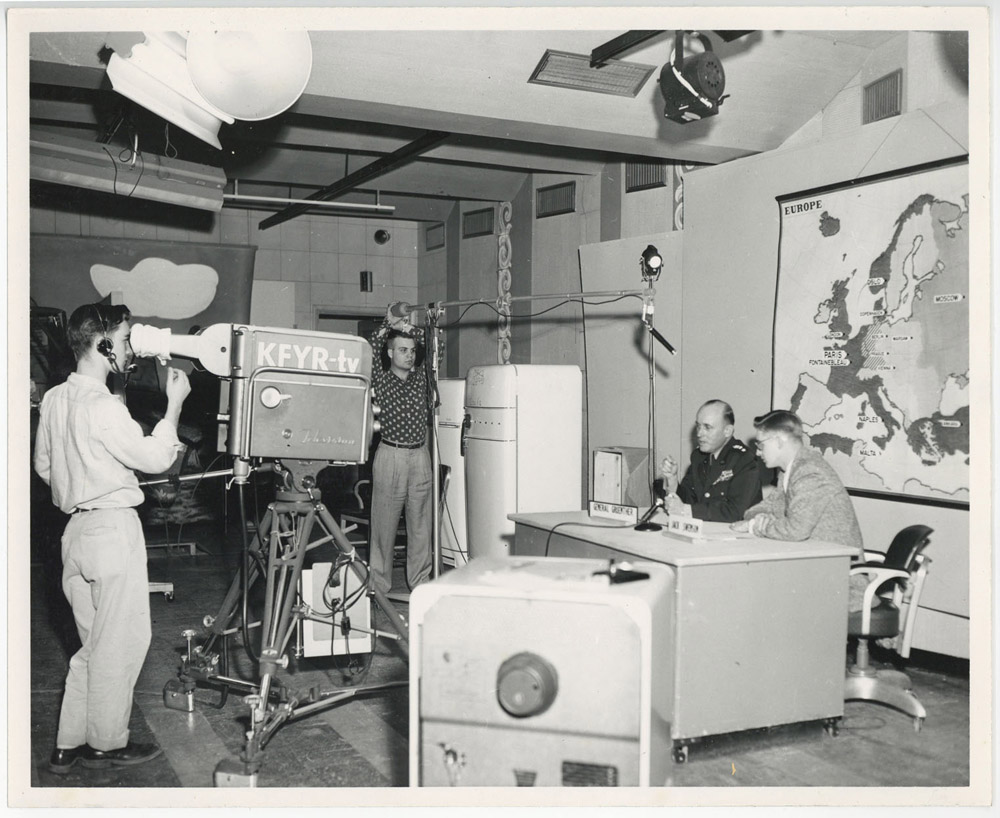

Most TV stations affiliated with a national broadcasting company such as NBC, ABC, or CBS. WDAY picked up programming from all three networks plus the now-defunct Dumont network. The networks sent films of TV shows for local stations to broadcast. The films arrived by airplane daily. The stations previewed the TV shows and projected the films for their own cameras at the designated hour. (See Image 20.)

Politicians quickly identified the value of television. Although television time was expensive, candidates for public office could reach many more people via television than through door-to-door campaigns or hand-shaking visits to church dinners. Fargo City Commission candidates appeared on WDAY-TV shortly after the station went on air. Four unsmiling, earnest-looking men spoke directly to the people through the TV camera about their qualifications for office. Their discomfort with the new medium was apparent, but both the TV station and the candidates understood the power of television to foster political participation in a democratic society.

Local TV stations paid their bills by selling advertising, so families bought a TV, but did not pay for programming. Local businesses were eager to have TV ads, but wanted to be sure that plenty of people were watching TV. The stations had to encourage people to watch their station. Producers and photographers learned to put the stations call lettersTelevision producers placed the station’s call letters and channel number on every camera. When a photographer went into the 'field' to photograph events, people would see the camera and watch that channel later to see what TV announcers had to say about the event.

One photographer, Bill Snyder of WDAY-TV in Fargo had a trick he used when covering public events. He asked to be paged with an announcement: 'Would the WDAY-TV news cameraman please report to the reviewing stand?' Everyone who heard the announcement became aware that the TV station was filming and reporting on the event. Later that day, they would be looking for themselves on TV. or number on cameras and to be sure that people at an event knew that they were being filmed for TV.

Television technology continued to improve. (See Image 21.) Before many years had passed, most North Dakota homes had televisions, though reception might have been irregular in rural areas until the 1980s. (See Image 22.) National network programming allowed North Dakotans to join people all over the country watching evening newscasts from New York or Washington, D.C. In the 1970s, cable television programming became widely available and people paid for access to cable channels. The number of channels and the kinds of programs expanded greatly.

Why is this important? Television changed North Dakota in many ways. North Dakotans watched “I Love Lucy” and other shows that people all over the country were watching. North Dakotans began to adopt peculiarities of language, dress, and customs that they saw on television.

Some critics have said that TV watching led to social isolation and broke down community ties. However, TV also gave people something to talk about with their neighbors. Families and neighbors got together to watch a sports event on TV. Television broadcast local events and events across the state. And North Dakota is still small enough that we can sometimes see ourselves or our friends on TV.

Eric Sevareid

More than a few North Dakotans have become television and movie stars including Josh Duhamel of Minot and Angie Dickinson who was born in Kulm. Eric Sevareid (1912-1992) was a different sort of TV star. He was a well-known and widely respected news reporter for CBS television.

Arnold Eric Sevareid was born in Velva where “wheat was the sole source and meaning of our lives.” He attended college at the University of Minnesota while working for The Minneapolis Journal. Soon after college, he and a friend set out to canoe the Red River from its source in South Dakota to its mouth at Hudson Bay. He wrote about the adventure in Canoeing with the Cree published in 1935.

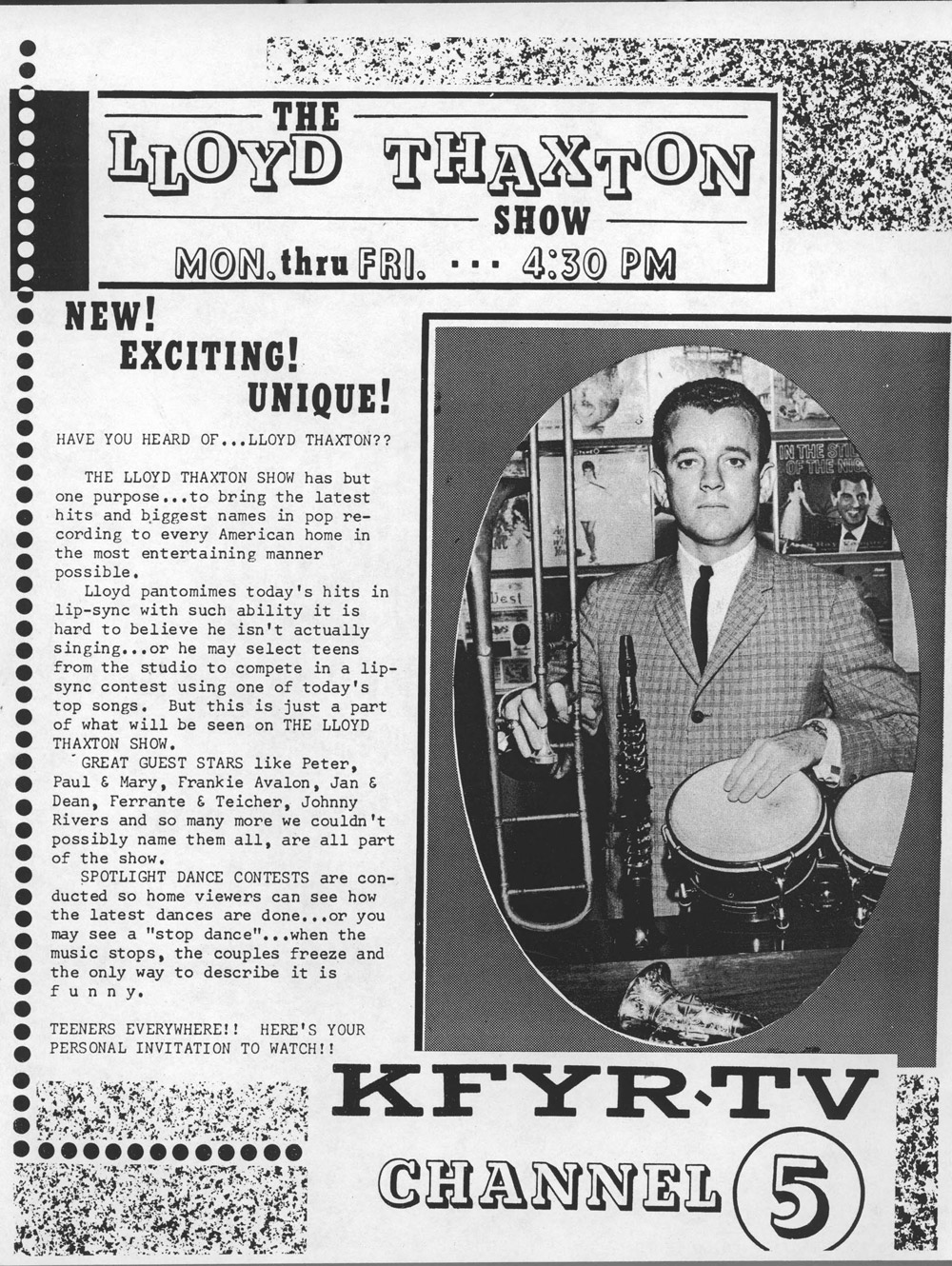

Sevareid became a reporter for CBS radio news in 1939 while he was covering the outbreak of World War II in Europe. (See Image 23.) He continued to report from Paris as the war expanded. He was the last American to broadcast a report from Paris as the Nazis approached the French capital. In 1943, Sevareid reported from the theatre of war in southeast Asia. While reporting from Asia, he had to bail out of an airplane into a jungle. It took a month for Sevareid and the other survivors to walk out of the jungle.

After World War II (1941-1945), Sevareid not only continued reporting international news, but became a commentator on the news. In 1966, reporting from the war zone in Vietnam, Sevareid supported bringing the war to a close as soon as possible. Reporters who added commentary to their reporting offered their opinions on the news, not just the facts. Sevareid was ruggedly handsome and had a deep voice which added power to his reporting and commentary.

Sevareid’s boyhood adventures helped him to focus his career on exciting locations and events. He was not afraid of taking a moral stand in his reporting and was willing to bear the challenges that resulted from his positions. As a young reporter for the The Minneapolis Journal he investigated the Silvershirts, a local anti-Semitic, fascist group. Members of the Silvershirts told Sevareid that their organization would “sweep . . . across the city.” The article was published in 1936 just as fascism was gaining power in Germany and Italy.

Though his article on the Silvershirts made the newspaper’s front page, Sevareid believed the editors did not give the movement serious consideration. His love of democracy and his growing empathy for laborers and the poor made him unwelcome at The Minneapolis Journal, and he was soon fired. These same qualities of honesty, fairness, and equality made Sevareid a respected television news reporter. Sevareid attributed many of his attitudes to his boyhood home in Velva. He sometimes wondered, “Why can’t the rest of the world be like us?”

Why is this important? Eric Sevareid was honored by North Dakota with the Rough Rider Award in 1964. He was not only a famous news reporter, but a man who honored his home state in his various books. As a child and a young man, he acquired values that stayed with him all of his life. These values gave him the moral strength to face the many challenges of his career. His books include Canoeing with the Cree and Not So Wild a Dream. Both are about his life and adventures in North Dakota and the ways that North Dakota shaped his life.