Baseball has been a popular sport in North Dakota since the 1880s. Almost every small town and the reservations had a baseball team with sharp-looking uniforms. (See Image 8.) Most of the smaller towns did not have a real baseball diamond. Bases were put in place in a large field; spectators’ cars outlined the outfield. Teams traveled from town to town by train to play their rivals. Sometimes teams claimed to be the “champions” of a region because they had defeated a few other teams, but there was no baseball organization to arrange tournaments or keep records.

By the 1920s, several North Dakota teams had hired a few African American players. While "Jim Crow" lawsIn most of the United States during the early part of the 20th century, African Americans were not allowed to enter public schools, theatres, restaurants, or other places. So-called “Jim Crow” laws prevented social mixing by people of different races. Because of these laws, African American baseball players were not allowed to play in the major leagues until 1947. African American players played for teams in the Negro Leagues. However, the financial instability of the Negro Leagues made it difficult for players to remain with one team very long, so it was easy for Churchill to hire a great player from the Negro Leagues. prevented social mixing of people of different races in many states, there were no such laws in North Dakota. Jamestown, an especially competitive baseball town, hired black semi-professional ballplayers in the 1920s. Catcher Solomon Otto and the great pitcher Barney Brown played a few games for Dickinson. (See Image 9.) Minnesota had a few mixed-race teams, but elsewhere in the United States baseball teams were not integrated.

In 1933, former semi-pro ballplayer, Bismarck auto dealer, and future mayor Neil Churchill looked for the best baseball players he could afford to strengthen his Bismarck baseball team. He put together a dream-team that included many talented local players, some semi-pro players from other states, and several players from the Negro Leagues including Quincy Trouppe, Roosevelt Davis, and Satchel Paige. Bismarck fielded this mixed-race team from 1933 to 1935.

Satchel Paige was already famous as one of greatest pitchers in all of baseball history. Satchel Paige was not only a great pitcher, but also a great showman. When he felt confident that his pitches would win the game, he sent the outfielders to the dugout and pitched to an opponent with an empty outfield. When Paige arrived in Bismarck, he found out that he would be playing on a mixed-race team. Paige reportedly said, “For the first time since I'd started playing, I was going to have some [white men] on my side. It seemed really funny.”

Churchill’s first concern was to win games against arch-rival Jamestown. The Jamestown team had also hired players from the Negro Leagues. Their pitcher was another great Negro League veteran, Barney Brown.

In the summer of 1933, Bismarck challenged Jamestown to a game. The Jamestown team traveled to Bismarck by train with 1,000 fans. The Bismarck stands were full. Bismarck won in an exciting game and traveled east to Jamestown a few weeks later for a re-match. Four thousand fans watched Bismarck win again.

The rivalry continued, but Bismarck also played many traveling teams, both all white and all black. Bismarck’s first season as a mixed-race team was wildly successful financially, too. Other serious baseball towns such as Valley City and New Rockford saw the advantage in hiring talented black players.

In September, 1934, a major league all-star team traveled through North Dakota on its way to Japan. Churchill put together a team made up of the best players in the state. The All-Stars played three games against North Dakota, and lost all three. One of the major league players remarked, "I knew there were a lot of good colored players. I just didn't know they were all in Bismarck!"

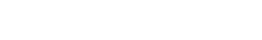

In 1935, Churchill added more pitchers and hitters to the roster, both white and black. (See Image 10.) The team had a great season that was crowned by winning the semi-pro baseball title at a tournament in Wichita, Kansas. Bismarck simply blew out the competition. After the game, Quincy Trouppe was told that he could earn “‘$100,000 to play ball if you were white.’ 'Well, Sir,' I said, 'We're available right now. I'm sure you've noticed that color doesn't mean a thing on our ball club.'”

Even Satchel Paige was impressed by the team. He told a reporter several years later, “That was the best team I ever saw; the best players I ever played with. But who ever heard of them?"

The 1936 season was again successful for Bismarck, but Neil Churchill resigned as manager, and some of the best players turned to other teams or other jobs. (See Image 11.) It was the last year for the Bismarck semi-pro team. However, Bismarck’s remarkable team had made such a great impression on baseball, that when Honus Wagner became commissioner of semi-pro baseball, he banned mixed-race teams from the national tournament.

Why is this important? It would be nice to say that the Bismarck baseball team led the way to the integration of baseball and other sports, but it did not. Satchel Paige was right when he said, “who ever heard of [the Bismarck baseball team]?” It was not until 1947 that Branch Rickey (another man who wanted to win) hired Jackie Robinson, the first African American to play Major League Baseball.

It would also be nice if we could say that this team represents a spirit of brotherhood that is characteristic of North Dakota. However, the players met racism in Bismarck that was deeply rooted and complicated. Players had to be careful about entering restaurants and hotels. Black players rented rooms in the homes of Bismarck’s black residents. And Satchel Paige was warned to avoid being seen with white women in Bismarck. On the other hand, black students attended Bismarck public schools, and the city embraced the whole team.

The Bismarck baseball team represented possibilities: the possibility that an athletic black man might make a good living in professional sports; the possibility that people could be appreciated for the contributions they make to a community, rather than what they look like; the possibility that North Dakota would not blow away in the heat and drought of the 1930s, but could take one small step toward making the United States a different place.